North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

Women and Children Face the Invader

From Woodrow Wilson’s History of the American People:

“It was a singular and noteworthy thing, the while, how little the quiet labor of the Negroes

was disturbed by the troubles of the time and the absence of their masters . . .

Gentlewomen presided still with unquestioned authority upon the secluded plantations –

their husbands, brothers, sons, men and youths alike, gone to the front.

Great gangs of cheery Negroes worked in the fields, planted and reaped and garnered and

did their lonely mistresses’ bidding in all things without restlessness, with quiet industry,

with show of faithful affection even.”

It is proper to begin this page with a period statement regarding the women of the South and the part they

played in supporting the home front as well as the war front; supporting the war effort along with the African

slaves in their care by rasing food for the armies, and providing the uniforms, blankets, socks and other material

necessary for the men in the field. When the end came, they had to face the enemy alone and with their hungry

and often destiture children by their sides.

The Temper of the Women:

“The women of the South could hardly have been more desperately in earnest than their husbands

and brothers and sons were, in the prosecution of the war, but with their women-natures they gave themselves

wholly to the cause.…to doubt its righteousness, or to falter in their loyalty to it while it lived, would have

been treason and infidelity; to do the like now that it is dead would be to them little less than sacrilege.

I wish I could adequately tell my reader of the part those women played in the war. If I could make

these pages show half of their nobleness; if I could describe the sufferings they endured, and tell of their

cheerfulness under it all; if the reader might guess the utter unselfishness with which they laid

themselves and the things they held nearest their hearts upon the altar of the only country they

knew as their own, the rare heroism with which they played their sorrowful part in a drama

which was to them a long tragedy;

[I]f my pages could be made to show the half of these things, all womankind, I am sure, would

tenderly cherish the record, and nobody would wonder again at the tenacity with which the

women of the South still hold their allegiance to the lost cause.

Theirs was a particularly hard lot. The real sorrows of war, like those of drunkenness, always fall more

heavily upon women. They may not bear arms. They may not even share the triumphs which

compensate their brethren for toil and suffering and danger. They must sit still and endure.

The poverty which war brings to them wears no cheerful face, but sits down with them to empty tables

and pinches them sorely in solitude.

After the victory….[the] wives and daughters await in sorest agony of suspense the news which may

bring hopeless desolation to their hearts. To them the victory may mean the loss of those for whom they

lived and in whom they hoped, while to those who have fought the battle it brings only gladness.

And all this was true of Southern women almost without exception.

[The] more heavily the war bore upon themselves, the more persistently did they demand that it should

be fought out to the end. When they lost a husband, a son, or a brother, they held the loss only

an additional reason for faithful adherence to the cause. Having made such a sacrifice to that which

was almost a religion to them, they had, if possible, less thought than ever of proving unfaithful to it.”

(A Rebel’s Recollections, pp. 83-85)

To best understand the temper of North Carolina's enemy in this conflict, it is worthwhile reading Northern

political statements and intentions, and news reports, with regard to the Southern people, and the waged

war upon them. This was borne out in time by Northern armies as they destroyed wide swaths of Southern

territory and confronted the families at home.

“Removal of the Remains of Washington

A correspondent of the Lynchburg [Virginia] “Republican” says:

“I was told today that a report having reached….Virginia that the tomb of [General George] Washington

was going to be violated by the [Northern] Republicans, his remains and those of his family were

promptly removed to a more central spot in the State, where they will be out of harm’s way.

If this is true, what a commentary on the North! How strange that coming events should prompt such a move!

Surely we live in a singular age.”

(Diary of Ada Amelia Costin, Tuesday, May 21, 1861)

Wading Through Blood of Men, Women and Children:

The following excerpts from the address made by Major [Henry W.] Conner in his campaign for

reelection to Congress in 1839 show how the smoldering fires of anti-slavery sentiment were beginning

to blaze in the North. Referring to it he said:

“Abolitionism, when I last addressed you seemed to be confined to a few fanatics only, and so

absurd seemed their views and pretensions that serious apprehension could not reasonably be

entertained, but such has been their rapid growth in a short time, that in several of the States they

hold the balance of power in politics, and abolitionism has, therefore, become a political question

with the avowed object of striking at the rights and property of the South, and there is reason to believe they

will not be particular in the mode of carrying out their plans, whether peacefully, or by wading

through blood of men, women and children.

The desks of abolition members (especially John Quincy Adams and Slade) are loaded with thousands

of antislavery petitions which have be presented within the last two years, asking Congress to interfere

with your rights and property. This heartless and unjustifiable policy must and will be met by the South

at the proper time with manly determination to protect and defend our rights and privileges at all hazards.”

(The Annals of Lincoln County, North Carolina, pp. 188-189)

Southerners Hanged or Exiled:

“Wendell Phillips, who, before the blood began to flow, eloquently declared that the South was in the

right, that Lincoln had no right to send armed men to coerce her, after battles begun seemed to

become drunk on the fumes of blood and mad for more than battlefields afforded. In a speech delivered in

[Henry Ward] Beecher’s church, to a large and presumably a Christian congregation,

Phillips made the following remarkable declaration:

“I do not believe in battles ending this war. You may plant a fort in every district of the South, you may take

possession of her capitals and hold them with your armies, but you have not begun to subdue her people.

I know it seems something like absolute barbarian conquest, I allow it, but I do not believe there will be any

peace until 347,000 men of the South are either hanged or exiled.” (Cheers).

Why the precise number, 347,000, does not appear. If the hanging at one fell swoop of 347,000 men and

women seemed to Phillips something like barbarian conquest, it would be interesting to know what

would have appeared truly barbarian. History records some crimes of such stupendous magnitude,

even to this day men shudder at their mention.”

(Facts and Falsehoods, Concerning the War on the South, pp. 235-236)

With relatively few Africans living amongst them, and those politically and socially-proscribed in the North,

Northerners had little real understanding or first-hand knowledge of life in the South and actual

black-white relations on the plantations.

"No Subject Has Ever Been So Misrepresented As This One"

“Dear Children -- Our faithful servant, Hollen, was without equal in my opinion. She was a most beautiful

seamstress, there was nothing in the way of fine work she could not do. She said, “I do not feel free unless

I go North” – I advised her to go and she secured a home with a Mr. and Mrs. White, at Chepachet, R.I.

They were, as many others at that time, interested in asking how the negroes were treated by their

owners in slavery times. So on long winter nights Hollen would regale them with tales of our plantation

life, and their surprise was great when they found how kind we were to the slaves.

No subject has ever been so misrepresented as has this one.

Quite a noted colored man was Arthur Simmons, who served as janitor of the “White House” through the term of

four presidents. He belonged to Mr. Attmore, of New Bern, North Carolina, who was a great friend of mine

when I was a young lady…You can imagine how my meeting [Arthur] at Washington some years ago brought

up so many recollections of the past. My son was with me and Arthur could not do enough to make our

visit interesting. In passing through several rooms we met a gentleman who proved

to be the Secretary of War, [Russell A.] Alger.

After our departure, he said to Arthur “Who was that lady and gentleman who seemed glad to see you and to whom

you were so very polite? Arthur told him with much gusto, and Mr. Alger replied, “We Northern people must

have misunderstood the friendly relation that existed between master and slave.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, pp. 12-13)

The following diary excerpts allow the reader today to calibrate their mind's eye to the ante-bellum and

wartime experienced by North Carolinans then -- and to help better understand their lives. While the men

of the family -- husbands, fathers, brothers, sons -- were off to war, the women and children had to maintain

the farm and face alone the wrath of the invader.

North Carolinian Estimate of Sherman's Associates

“On March 7, 1865 General William T. Sherman and his army of mercenaries from Germany, Ireland,

Scotland, Sweden, Switzerland and Prussia, as well as the northern United States, many of whom

could not speak English, crossed the North Carolina State line.

Behind them lay the smoking ruins of sacked Georgia and South Carolina cities, homeless widows

and orphans, and death by starvation. At Laurel Hill, NC, Sherman halted to refresh his troops, and from

here he wired General Schofield in Wilmington that he would be in Goldsboro, NC March 20, 1865

via Fayetteville, NC. On March 12th Sherman and his army of barbarians reached Fayetteville.

After plundering the residential section, it was then burned. Also destroyed were four cotton mills,

the churches, banks, courthouse and warehouses. Sherman then moved on looting and burning.

Any item that could not be carried, including furniture, carpets and farm equipment, was destroyed.

Even the cabins of the slaves were robbed by the Yankees.”

(Land of the Golden River, page 101)

The Cruel Yankee Enemy:

June 7 (1863). Sunday (Diary entry):

"From every side evidences of the barbarity, savageness, and insolent assumption of the

Yankee government in the policy on which they have resolved in the conduct of the war, thicken.

The policy fully disclosed is to trample out all opposition in all places which come into their possession,

even if it leads to a deportation of the whole population. They have Negro regiments in every military

department except Hooker's, mostly enrolled in the South. Massachusetts with

characteristic regard for consistency, principle, and thrift is sending her [non-resident] Negroes

to the wars to be killed off, a clear gain every way.

A letter (circular) was captured on a vessel taken on the Neuse (N.C.) some days ago, addressed

to General (John G.) Foster by (Augustus S. Montgomery) dated Washington City, which proposed

a plan for organizing a general insurrection on August 4 next throughout the Confederate States

to be supported by United States armies.

The slaves were to be informed through the contrabands, and the circular was to be passed from

one military commander to another, each writing below, without his signature, the word "approved"

so that the friends of the enterprise might know how far it had the support of the military authorities,

and that they might each be aware that it was generally known and approved. Copies of this were

sent by [North Carolina] Governor Vance to the War Department and to General Lee. This diabolism

was not authenticated by any government authority, but bore evidences of having

the countenance of the United States Government.

There is nothing which they suppose tends to the destruction of the South which they are not prompt

to embrace....The Earth contains no race so lost to every sentiment of manliness, honor, faith or humanity,

at once so servile and so tyrannical, so mean and so cruel, such willing slaves, and so bent on

destroying the independence and existence of their enemy."

(Inside the Confederate Government, pp. 69-71)

"In The Country of the Enemy"

Dec. 22, 1862

"At one point the column was confronted by a spunky secesh female, who, with the heavy

wooden rake, stood guard over her winter's store of sweet potatoes. Her eyes flashed defiance,

but so long as she stood upon the defensive no molestation was offered her. When...she changed

her tactics and slapped a cavalry officer in the face, gone were her sweet potatoes and other stores

in the twinkling of an eye."

Feb 8th, 1863

"Leaving the Washington [North Carolina] road on our right.....we were not long in ascertaining the fact

that we were on a foraging expedition, and if history should call it a reconnaissance, the misnomer will never

restock the stables and storehouses, the bee-hives and hen-roosts, that night depleted along the road of Long Acre.

We received an early hint that we were going to capture a lot of bacon twelve miles out of Plymouth,

but if the residents along the road this side that point managed to save their own bacon and things,

they certainly had reason to bless their stars. If it would not be considered unsoldierly and sentimental,

your correspondent might feel inclined to deprecate this business of foraging, as it is carried on.

It is pitiful to see homes once, perhaps, famed for their hospitality, entered and robbed; even if the robbers

respect the code of war. It is not less hard for women and children to be deprived of the means of subsistence

because their husbands and sons and brothers are shooting at us from the bush. But war is a great,

a terrible, an undiscriminating monster, and no earthly power may stay the ravages of the unleashed brute."

"In The Country of the Enemy," Diary of a Massachusetts Corporal, pp. 102-103

Pianos and Furniture for Northern Homes:

".....(I)t was during the winter of 1862-63 that General Foster made a raid from New Berne up to near

Tarboro, NC, and as soon as I could ascertain his designs and objective I began to concentrate troops

to meet him. Foster was at a village about twelve miles distant. In the morning Foster was far away

on his road to New Berne....it was cold and snow covered the ground,

and pursuit was useless except by cavalry.

I am quite sure vandalism (especially stealing) commenced in New Berne, for the pianos and furniture

shipped from there decorate to-day many a Northern home. At Hamilton most of the dwellings had

been entered, mirrors broken, furniture smashed, doors torn from their hinges, and especially were the

feather beds emptied into the streets, spokes of carriage wheels broken , and cows shot in the

fields by the roadside, etc. It was a pitiful sight to see the women and children in their destitute

condition. Alas! Toward the end (of the war) it was an everyday occurrence, and the main object

of small expeditions was to steal private property."

(Two Wars, General Samuel G. French, pp. 150-152)

A North Carolina Mother’s Diary

April 13: Preaching at Beth Car. Mr. McDonald’s text was in Matthew 24th Chapter and

44th verse. I spent the evening at Mr. James Robeson’s, and Mrs. M.E. McDowell

came home with me and staid all night.

April 21st: Sabbath day. We all went to the Methodist church – life & death, peace and war.

April 22nd: To Miss Ellen Owen’s. The whole topic of conversation was about the distressing

state of the country. I am heart sick, I know not what to do.

April 26th: Friday. The boys started to Muster, Johnny Whitted with them. He staid here last night.

Evening has come, the boys have come. Evander has volunteered.

May 10th: Mary Allen, Amelia Allen and Betsey Devand and myself busily engaged making

mattresses, flanen shirts, etc. for the volunteers.

May 13th: A day long to be remembered by me and many other sorrowing mothers. Our sons have

left us, we know not when (if ever) they will return. We can only commend or commit them to the care

of our Heavenly Father who hath said “Peace, be still.” He can comfort them, strengthen them,

and cause them to stand…Oh kind parent and Giver of all good, grant that my son may not

shed blood…I sincerely hope that with Divine assistance all grievances may be settled

without any more bloodshed.

1862

May 13th: This day 12 months my son Evander left home for the Army, how much longer he will

have to stay I know not but trust and hope the All Wise disposer of events will so order it that I may

again see my poor boy alive and well, not that I deserve it any more than any other mother,

for many a better mother than I have lost their all on the battle field, but Oh! Heavenly Father,

let that bitter cup pass me, but not my will but thine be done, Oh! Lord.

May 30th: I got a letter from Evander saying he is well and at Louisa C.H., Va.

And expect to be in a Battle ere [long]. O! Lord, keep my poor boy under the shadow of (Thy] wings

and convict and convert my poor wandering boy’s heart and if he is to fall in Battle he may be a fit heir

for thy Kingdom. I ask this not for any worthiness of my own for I am a miserable sinner, but for the

sake of thy son Jesus who died that I might live.

June 1st: I am alone and wretched. Mr. W. Cain came in and says he heard our boys [Bladen Guards]

were in the Battle and cut to pieces. I sincerely hope it is not so. O! Merciful Father, if I should here

my poor boy is killed sustain me in that hour of trial.

June 3rd: We called at Mr. Monroe’s and saw a list of the killed and wounded, 6 of the

Bladen Guards are killed, 3 wounded and 12 taken prisoner. Albert Rinaldi is killed. I am truly

sorry for his poor mother, but she has one consolation, her poor boy had embraced religion

and she sorrows not as one who has no hope.

(Diary of Elizabeth Ellis Robeson, Bladen County, NC, pp. 114-122)

Fuel and Toys of Goths and Vandals:

“Almost in the twinkling of an eye the whole social fabric of the South was swept away, and a half-century

has hardly sufficed to produce an entire readjustment to new conditions, so fundamental was the change.

The libraries and colleges, indeed all institutions that fostered and conserved its culture, suffered heaviest.

Almost every school building in the South was occupied at one time or other by soldiers as barracks

or hospitals, and books and instruments of unknown value were used as fuel or served as toys for the idle

hours of high privates. In many of the libraries, broken sets and mutilated volumes still remain as pathetic

reminders of the days of blood and fire.

The famous library at Charleston was partially destroyed, the building being used as a military hospital;

all the Virginia institutions suffered greatly, as did those in Kentucky and Tennessee. The most astonishing

episode, however, of the kind, in that most astonishing conflict, was the burning of the library building and

collections of the University of Alabama, during the final days of the war. This library, which was one of the

largest and best selected in the South, was ruthlessly destroyed at a time when the issue of the conflict

had been decided, and no conceivable gain could have resulted from such an action.

Of the influence of his books upon the man of the early South, we are permitted to judge by the work the

Southerner did in the forming of the nation. [The] schools and libraries of ante-bellum days surely had a

large share in the development of the men who defended, by impassioned speech and heroic deed, social

traditions and an ideal of the state doomed by the spirit of progress.”

(The South in the Building of the Nation, Volume VII, Edwin Wiley,

"The Battle of New Bern and Aftermath"

“Dear Children -- When Amy, my black mammy died, I was sent for, and mingled my tears along with the

dusky mourners about her coffin. In great contrast indeed, to this one day just after my return home after the

close of war and during that awful reconstruction period, I was walking along quietly on Broad street, when a fat

buxo[m] mulatto wench came up to me, and shaking her fist in my face ordered me off the side-walk.

I quickly looked up and seeing no white person visible, and the streets full of negroes, as a church had just

emptied itself into the streets, I stepped aside into the gutter and went home. I will not tell what

I thought on that occasion. (What sort of Christian teachings were preached inside those black churches?)

“The winter of ’61 was a most anxious one, we did not know what would be the result of so much political

agitation. Soon we heard news that Fort [Sumter] had fallen, then people began to talk of war and went to

raising companies and regiments. New Bern, being in an exposed position, it was thought best for as

many women and children as could leave to do so. In March, ’62 the Battle of New Bern occurred and

such a time of confusion and trouble!

We had extra dinners prepared, expecting to feed Confederate soldiers. Instead of that, there was perfect

panic and stampede, women, children, nurses, and baggage getting to the depot any way they could.

Our home and hundreds of others were left with the dinners cooking, doors open and everything to

give our Northern friends a royal feast, which I understand they thoroughly enjoyed.”

{When] we returned home at the close of the war, we found our beautiful and valued farm an abandoned

plantation, even the cedars that divided the fields, had been cut down, the nice comfortable negro cabins had

been dismantled, as also the barns and outhouses, the old Colonial brick dwelling, made of bricks from

England, was razed to the ground. Horses, cattle, sheep, of course, gone, and an apple orchard

of choice apples destroyed.

The refugees, as a general thing, were not cordially received by the up-country people. We went to several

places before finally settling, to Greensboro, Lexington, and lastly to a tiny farm four miles from Raleigh.

We had constant communication with Raleigh, the news of terrible battles in which our nearest and dearest

were either wounded or killed, kept [us] very unhappy. It was hard to get provisions, everything that could be

spared was sent to the army. Both your Grandmothers were kept busy knitting socks for the soldiers,

we cut up carpets for blankets, and sent blankets also, and used comfortable in their place;

boxes went off every day filled with necessary things for our boys.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, pp. 23-24)

"The Night of Horror Wore On"

“Dear Children -- One night, we had quite an experience in our country home. My Mother came from her room

above and said there were strange noises in the yard, the negroes were singing

“Hurrah! Hurrah! We are free! We are free!”

We peeped out of the narrow window, and there, sure enough, were many negroes singing and dancing

around the fire, with every demonstration of joy, and every little while we heard the fife and drum. We sprang out of

bed very much frightened, dressed ourselves, made a fire in the huge chimney place and anxiously awaited for

what was to come. Our feelings cannot be described. I looked at my daughter sleeping so peacefully in her crib

and thought that before morning the last of my race would be swept away; at my patient and invalid mother,

what a death for her to die! And perhaps that very night, none of us would be left to tell the tale. But the night

of horror wore on – and the morning dawned peaceful and bright with no evidence the mortal agony we had endured.

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, pp. 24-25)

"Scarlett Fever in Raleigh"

“Dear Children -- About this time, we succeeded in getting in Raleigh a small house of four rooms; we built

a log pantry and rented a kitchen on the next lot. Scarlet fever broke out and many, both white and black, died.

I was sitting by the fire in our cabin when Olly, a very good [black] servant, came in the room with a sick baby

in her arms; it grew rapidly worse, and as I took it from her, the breath left its little body.

I was completely unnerved; my little son had been taken away and the girl was a delicate baby and I knew

how deadly a disease scarlet fever was. I had the carriage ordered, put a few things in a traveling bag, took

nurse and baby and started away, I knew not whither; toward dark we drew up at a county place near

Wake Forest where my aunt was refugeeing. Before descending from the carriage, I told her from what I was

fleeing, but before I could finish, her big heart opened, her big arms took us in, and we were welcome.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, page 26)

"Offering Up His Life for a True, But Lost Cause"

“Dear Children – We had so many relations and friends in the army that we were always anxious.

Georgie…graduated from Chapel Hill in 1860, and was offered a Greek tutorship, which he accepted. He was

only eighteen years old, his only thought was books and religion; he cared nothing for politics, and intended

to study for the Episcopal ministry. But the cruel war had taken him, as it did thousands of our bravest

and best. George was made captain in the 2nd [North Carolina] Cavalry and fought gallantly until he lost his

life in the summer of 1864. Never shall I forget that dreadful day when the telegram came announcing that

he fell leading his men, and with the last words: “I am killed, boys, I wish I could live to take those works.”

He went into battle on August 16, 1864; he mounted his black horse and rode to death. His remains were buried

on some man’s farm, six miles from Richmond. There in the corner of the fence with only his oilcloth around him,

with only the birds to sing a requiem and the leaves to wave in pity, lies one of the bravest hearts that ever

offered up his life for a true but lost cause.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, page 27)

"Fall of the Confederacy Unexpected to the Last"

“Dear Children – One warm day in April [1865], a great many ladies and children assembled in the public

square in Raleigh, near the Capitol, all anxious to hear the news…some one said “It is reported that Lee

has surrendered” -- such consternation on the faces of the people, then as the news became more general,

such weeping and wringing of hands, such heavy hearts – privation, sorrow, death, defeat and poverty.

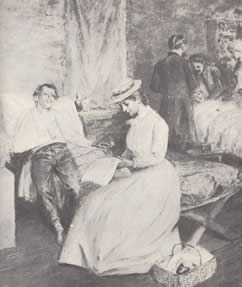

Raleigh was now filled with wounded and disabled soldiers; the churches and every available space turned

into hospitals. I did what I could, but it seemed nothing. The Episcopal church being nearer to me, I went

there mostly; many poor men were on the benches, some in high delirium, some in the agony of death.

A young soldier passed away, none knew his name or home; as the coffin lid was being screwed down,

a dear lady pressed her lips to his brow, and said: “Let me kiss him for his Mother.”

Every heart responded and all eyes filled with tears. Volumes of heartrending and pathetic incidents could

be written of our four years’ cruel war. Although we were becoming less hopeful, yet the Fall of the

Confederacy was unexpected to the last.

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, page 28)

Resisting the Vandals

“Only a Southerner can fully understand a devotion between master and slave so deep

that a slave often accompanied his master to battle to serve and protect him . . . . [and] Some

slaves proved their loyalty to their white masters in the most tangible of ways: they risked or

gave their lives rather than betray their masters.

“When the Yankee soldiers reached my grandfather’s plantation they took the slave who had

helped hide his valuables and knew where everything was and tried to make him tell on his master.

But he would tell then nothing. They took him in the front yard, made him lie down on the ground,

held the muzzle of a gun to his mouth, and told him they would shoot if he did not talk.

He refused to betray his master, and the soldiers let him go unharmed.

The soldiers never found the treasure.

(True Tales of the South at War, Clarence Poe, editor, Dover, 1995, pg. 188)

Hung for Protecting His Master

“In front of Hopewell Associated Reformed Church in Chester, South Carolina, is a memorial

stone for Burwell Hemphill [, a slave] of Robert Hemphill, a member of Hopewell Church. Indeed,

both master and slave were members of this church. The stone commemorates the fact that

Burwell . . . was hung by Sherman’s raiders when they passed through this section. The raiders

tried to make Burwell reveal the hiding place of his master’s valuables. They swung him

several times, then would lower him down, and would try each time to make him tell where he

had hidden those things. Truly he had given his life for his master. He died rather than be

unfaithful to those he loved and served.”

(True Tales of the South at War, Clarence Poe, editor, pg. 188)

Hung for Defending His Country

“Dear Children – Soon our troops began to pass through [Raleigh, April 1865], weary, dirty fellows,

and hungry also, every one that could, fed them; they could not stop but in passing, we stood at the gate

and handed them bread and ham; they were marching to the tune of Dixie, the war song that we vainly

thought was going to lead them to victory.

Our soldiers retreated towards Hillsboro, the Federal soldiers pursuing.

One reckless Confederate soldier from Texas was in the rear guard; he fired on a Yankee soldier,

so close were the pursuers to the pursued. After firing he turned and put spurs to his horse, but

unfortunately his horse stumbled, and he was captured. The next morning under a guard of soldiers,

he was carried by our home, (I looked on with anguished heart) to the grove back of your Grandfather’s,

and hung to the limb of a huge tree, under which your uncles and aunts had played in childhood.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, page 29)

“Dear Children – We had begun to get quite comfortably fixed in our refugee home, when Raleigh

was captured. Of course we asked for a guard or our house would have been sacked. As it was,

everything was taken that possibly could be. Our fine cow was killed and only a steak cut from

her side; the horse was killed also and a little colt left which we fed from a bottle.

Everybody adjusted themselves to the changed circumstances and went to work to repair their

shattered fortunes. The after effects were as trying as the war itself, the disgusting Reconstruction

period was a disgrace to all concerned. We submitted to the inevitable…the ruthless destruction of

our dearly loved plantations, the pillage of our homes, and then all we asked was to be let alone and

rebuild as our judgment told us was for the best. Reconstruction times as you may well know, was

trying to men’s souls, “getting back into the union” was a favorite expression, and in some ways

these times were worse even than the war.”

(A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, page 30)

Sons at War and Refugeeing Daughters:

“For Mary Allan Wright [of Wilmington] the war clouds must have appeared especially dark.

She lost her eyesight in 1856 and her beloved husband in 1861. Her four surviving sons all

took part in the Civil War. Adam Empie Wright survived it unscathed. Joshua Grainger Wright

was wounded. James Allan was killed on June 26, 1862. Charles Thomas died May 26, 1864.

After the war, his brother, Joshua Grainger wrote [to his aunt, Julia Wear]:

“Our youngest brother Charles Thomas, aged seventeen, received his death wound at the Battle

of the Wilderness, while acting as adjutant. Although so young, it was impossible to keep him from

what he deemed the path of duty. Nothing but the most implicit faith and submission to God’s will

enabled my dear mother to bear the heavy trials of such distressing times. Those only who have been

afflicted as we have been, know what it is like to lose such dear and noble sons. As you are living in the

country we hope you are spared the mortification of seeing Yankee Officers….and trust the day may not

be far distant when we will be rid of [them].”

Young Joshua wrote from Fayetteville where the female members of his family had refugee the last three

years of the war. [The Wright women had] doubtless… heard stories of Yankee atrocities, such as the

ones Melinda Ray of Fayetteville told.

“Gentlemen were hung up and shot at to extort from them where their imaginary treasure was

concealed. (One man) was hung up twice, shot at once, and finally his house was burnt. (The Yankees]

behaved as bummers or wretches, feeling no delicacy in helping themselves to silver, books, or any

other particle they particularly fancied; and acting in the most disagreeable manner. Blair, a Yankee General,

boasted while here that he had all the silver belonging to Colonel McFarlane

of Cheraw, South Carolina in his possession.”

(The Wrights of Wilmington, pp. 78-79)

“They Whipped Mrs. R.”

Chester, South Carolina, [February]. 27, 1865

“My Darling Sister, I am so rejoiced to be able to once more write you though it is more than probable

this letter may never reach its destination. Every day we were in hourly expectation of a visit from Sherman’s

troops. When Columbia was evacuated they sent all the Government stores to this place….The Treasury

Department went through to Charlotte. I saw a good many of the girls….only stayed a few hours and

were very anxious for me to go to North Carolina…..

I must tell you some of the outrages the Yankees have committed around here. An old man by

the name of Brice lived in Fairfield District….The Yankees hung him because he would not tell where

he had hid his money and silver. They robbed every house they passed, burnt a great many. They have

burnt Tom Boulware’s and some houses near there, burnt Mary S. DeG’s gin house, cribs, etc.,

and took two watches and some other things from here.

They stripped old Mrs. R., Kate’s mother, and whipped her, destroyed everything Mrs. N. Beckham had

to eat and the Boulware’s and Watson’s, I hear, are living off the corn left by our cavalry men in the woods.

It has been some time since I have had as comfortable a night’s rest as I had last night…

.

Wheeler’s men killed sixteen Yanks I hear in retaliation for whipping Mrs. R. Oh Ann, I do think the idea of

a Lady’s being stripped and whipped by those villains is outrageous, the most awful thing I have heard of.

Oh Annie, is it not awful to see the way our people are suffering and the sin that is committed…..

I just know people cannot die from fear…..”

(When Sherman Came: Southern Women and the “Great March,” pp. 229-230)

The Lowest Types of Poor Buckra:

The enemy cavalry reached Lancaster, South Carolina on 23 February 1865 as it continued

its feint towards Charlotte. The invader had crossed “the Catawba at Rocky Mount” known

for its scenes of a previous invader and struggle for American independence.

From Mrs. J.H. Foster’s Diary:

“We awaited the coming of Sherman’s army with the greatest apprehension, for the reports that

preceded its approach of the destruction and burning of everything in its wake were calculated to

arouse the alarm of any civilized community. I was standing in a high back porch, looking towards

the old Methodist Church, when I saw one, two, then several, Yankees riding rapidly to Main

street crossing; then I heard a gun fired, an a Negro girl ran through the hall and, in great

excitement, said: “Lor’, they done killed old Mr. Jack Crockett.”

He was an old citizen who was too old to go to the war, to which he gave his two sons. He was crossing

the street just as the Yankees rode into town, and they fired, without hitting him.

This, the beginning of the rabble, was rapidly increasing in numbers. They were entering residences on

every hand, and as I turned to enter the hall, numbers were rapidly entering our front door and, very

unceremoniously walking into bedrooms or other rooms; they asked for food, proceeded into

closets, the storeroom, dairy, smokehouse. If the keys were not furnished, the butt end of a musket

served to shiver the timbers, that they might gain access.

There were but few men in town. The white women and children, and their Negroes, were there to

meet the emergency as best they could. As children, we looked with wonder at all those rude

soldiers, going through closets, cupboards, drawers; desecrating, even by the touch of their hands,

the very Lares and Penates of our household.

We could see that our mother was very much exercised, for she thought best to unlock every door,

drawer, or any place they might suspect her of hiding gold or silver, of which they seemed to think we had plenty.

Those Yankees filled their knapsacks with whatever pleased their fancy. The hams were tied to their

saddles, or slung two across, and they ransacked every nook and cranny of the house. Many of them

seemed drunk to me. They asked for whiskey, but my mother said she had none. They did not believe

her and went searching through everything for it.

Several of them took the house servants and searched them for the jewelry we might have hidden

on them. Even old mammy was forced to the smokehouse by threats and the pistol, to give up anything

she had concealed. Our Negroes were too indignant over this treatment ever to have any use for Yankees.

They believed them to be the lowest types of ‘poor buckra”….and their minds seemed set upon finding treasure.”

When Sherman Came: Southern Women and the “Great March,” pp. 230-232)

Vandals Liberate Furniture in Wilmington:

“The Federal troops captured Wilmington on February 21, 1865; they took possession of our home,

which we had temporarily vacated, and it remained General Hawley’s Headquarters a long time, even after

Lee’s surrender. It was very galling…”

[Mother] came up to own dear house, accompanied by a friendly neighbor…who was related to

General Hawley, and had offered to introduce her. It was most humiliating, and trying, to be entertained

by Mrs. Hawley, in her own parlor. Mrs. Hawley showed her raising by “hawking and spitting”

in the fire, a most unlady-like act. During the call she offered Mother some figs (from Mother’s own tree)

which Aunt Sarah had picked---our own old cook, who had been left there in charge of the premises.

My father made several trips to…Washington City before they would grant him his “Pardon.”

For what? For being a Southern Gentlemen, a Rebel, and a large Slave Owner! The slaves he had

inherited from his father, and which he considered a sacred trust. Being a physician, he guarded

their health, kept a faithful overseer to look after them (his home being a regular drug store), and

employed a Methodist minister, Rev. Mr. Turrentine, by the year, to look after their spiritual welfare.

Although the war was practically over seven months, we did not get possession of our home

‘till September. [T]he beautiful white marble mantles in the two parlors were so caked with tobacco

spit and garbs of chewed tobacco, they were cleaned with great difficulty; indeed, the white marble

hearths are still stained…No furniture had been left in the parlors…On leaving here, the Yankees gave

[the] furniture to a servant…” In our sitting room, our large mahogany bookcase was left, as it was too

bulky for them to carry off; but from its drawers numerous things were taken, among them an

autograph album belonging to me brother Marsden.

A number of years later, when my brother John was in Washington as a member of Congress, this

same Hawley, then a senator from Illinois, told him of the album “coming into his possession” when

he occupied our house, and said he would restore it to him. However, he took care not to do it,

although repeatedly reminded.”

(Back With The Tide, pp. 5-8)

Vandals Pickaxe the Pews Again:

“After the capture of Wilmington this venerable church, established in 1738, was seized by order

of General Hawley for a military hospital, and in giving an account of it the rector, Dr. Watson

(afterward Bishop of the Diocese) reported to the Diocesan Convention of 1866 as follows:

“This was not the first calamity of the sort in the history of the Parish Church of St. James.

In 1780, during the occupation of Wilmington by British troops the church was stripped of its pews and

furniture, and converted, first into a hospital, then into a blockhouse, and finally into a riding school

for Tarleton’s dragoons.

In 1865 the pews were once again torn out with pickaxes…There was sufficient room elsewhere,

more suitable for hospital purposes. Other hospitals had to be emptied to supply even half the

beds in the church which were indeed, never more than half filled.”

(Some Memories of My Life, Alfred Moore Waddell, Edwards & Broughton, pp. 58-59)

If You Had Behaved Yourselves, This Would Not Have Happened

“…[T]he Yankees came by the hundreds and destroyed everything that we possessed---every living thing.

After they had taken everything out of the house---our clothes, shoes, hats, and even my children’s

clothes---my husband was made to take off his boots which a yankee tried on. The shoes would

not fit, so the soldier cut them to pieces. They even destroyed the medicine we had.

In the cellar, they took six barrels of lard, honey and preserves---and what they did not want, they let

the negroes come in and take. They took 16 horses, one mule, all of the oxen, every cow, every plough,

even the hoes, and four vehicles. The soldiers filled them with meat and pulled them to camp which was

not far from our home. They would kill the hogs in the fields, cut them in halves with the hair on.

Not a turkey, duck or chicken was left.

My mother in law…was very old and frail and in bed. They went in her bedroom and cursed her.

They took all our books and threw them in the woods. I had my silver and jewelry buried

in the swamp for two months.

We went to Faison Depot and bought an old horse that we cleaned up, fed and dosed, but which

died after a week’s care. Then the boys went again and bought an ox. They made something like a plough

which they used to finish the crop with. Our knives were pieces of hoop iron sharpened, and our forks

were made of cane---but it was enough for the little we had to eat.

All of which I have written was the last year and month of the sad, sad war (March and April, 1865).

It is as fresh in my memory and all its horrors as if it were just a few weeks ago. It will never be erased

from my memory as long as life shall last.

I do not and cannot with truth say I have forgotten or that I have forgiven them. They destroyed what they

could of the new house and took every key and put them in the turpentine boxes. Such disappointment

cannot be imagined. My children would cry for bread, but there was none. A yankee took a piece out of

his bag and bit it, and said: “If you had behaved yourselves this would not have happened.”

(Story in Sampson Independent, February 1960; The Heritage of Sampson County (NC), pp. 253-254)

The Yankee Chaplain’s Looted Library:

“Many years after the war, Dr. Joseph G.D. Hamilton happened to run across [Major-General Robert F.] Hoke

and his son-in-law at a restaurant in Raleigh. As the men sat together on the porch before dinner,

Hoke rested quietly, gazing off in the distance.

In a tone designed not to arouse the reticent old soldier, Hamilton began to relate a newspaper

story about an event that had occurred after the surrender of Plymouth. A Federal chaplain who had been

denied officer’s privileges and “his” library called on Hoke, who responded favorably to his pleas.

After the chaplain left, the general noticed two large wooden boxes. When he enquired about the contents,

a soldier responded, “They are the books of that Yankee chaplain.”

Hoke noticed that the top of one of the boxes was broken, so he removed a book. It bore the bookplate

of Josiah Collins of nearby Somerset Place in Washington County. When the boxes were torn open, it

was seen that all the books were likewise marked.

The chaplain was immediately summoned to Hoke’s headquarters, where the general dressed him

down and stripped him of all privileges.”

(General Robert F. Hoke, Lee’s Modest General, page 153)

Sherman’s Fiends Incarnate Liberate Women’s Clothing

“Where home used to be. April 12, 1865”

Your precious letter, my dear Janie, was received night before last, and the pleasure that it afforded me,

and indeed the whole family, I leave for you to imagine, [and I am thankful] when I hear that my friends are left

with the necessities of life, and unpolluted by the touch of Sherman’s Hell-hounds.

My experience since we parted has indeed been sad…..[S]uch an army of patriots [as ours] fighting for their

hearthstones is not to be conquered by such fiends incarnate as fill the ranks of Sherman’s army. Our political

sky does seem darkened with a fearful cloud, but when compared with the situation of our fore-fathers,

I can but take courage.

[At] about four o’clock the Yankees came charging, yelling and howling. They just knocked down all such

like mad cattle. Right into the house, breaking open bureau drawers of all kinds faster than I could unlock.

They cursed us for having hid everything and made bold threats if certain things were not brought to light,

but all to no effect. They took Pa’s hat and stuck him pretty badly with a bayonet to make him disclose

something…The Negroes are bitterly prejudiced to his minions. They were treated, if possible, worse

than the white people, all their provisions taken and their clothes destroyed and some carried off.

They left no living thing in Smithville but the people. One old hen played sick and thus saved her neck,

but lost all of her children. The Yankees would run all over the yard to catch the little things to squeeze to death.

Every nook and corner of the premises was searched and the things that they didn’t use were burned or

torn into strings. No house but the blacksmith shop was burned, but into the flames they threw every

tool, plow, etc., that was on the place. The battlefield does not compare with [the Yankees] in point of stench.

I don’t believe they have been washed since the day they were born. I was too angry to eat or sleep…

Gen. Slocum with two other hyenas of his rank, rode up with his body-guard and introduced themselves

with great pomp, but I never noticed them at all.

Sis Susan was sick in bed and they searched the very pillows that she was lying on, and keeping

up such a noise, tearing up and breaking to pieces, that the Generals couldn’t hear themselves talk,

but not a time did they try to prevent it. They got all of my stockings and some of our collars and

handkerchiefs. If I ever see a Yankee woman, I intend to whip her and take the clothes off her very back.”

(Janie Smith’s Letter (excerpts), Mrs. Thomas H. Webb Collection, NC Division of Archives & History)

William Henry Belk was a child of three in 1865 when his father Abel was murdered by Sherman’s

bummers, leaving his mother Sarah not only a widow but with three babies and several

Negro hands to feed and clothe. The industrious William would be working his first job in

Monroe, North Carolina at age fourteen, and at twenty-six had started his own business which

eventually spread to every State in the South.

Sarah Walkup Belk

"God Will Protect Us; God Will Take Care of Us"

“Across more than four-fifths of a century of incredible change William Henry Belk remembers

the day his father left home to escape the advancing Federals. It was 1865, and the Confederacy

was dragging wearily into its last days. The South was almost prostrate now; even Sarah Walkup

Belk’s beloved Waxhaw country, the country of Andrew Jackson, the gallant William Richardson

Davie, and her own Wauchope family, lay under the heel and torch of Sherman.

This Federal general . . . was moving north after his march to the sea, pillaging and burning

and slaughtering, and in the path of his troops, in the border region between South Carolina

and North Carolina, lay the modest home of Abel Washington Belk.

If young Belk, whose weak lungs had prevented his joining the Confederate army, should be found

at home, the Belk’s feared that Sherman’s men would steal his property, burn the house, and

possibly hang him. If he should leave and hide out with some of the Negroes and the valuables

that could be removed, the Yankee marauders might spare the house . . . over the heads of a

defenseless young woman and her three babies.

So he loaded up the wagons and took some of the Negroes and they went down to Gill’s Creek some

fifteen miles east of Lancaster, South Carolina . . . refugeeing on the creek down there until the

Yankees had got out of the country. And it wasn’t long before the Yankees caught a fellow . . .

who figured he’d save his own hide and get in their good graces by turning up my grandfather,

old man Tom Belk. This scoundrel told them that my grandfather had

barrels of gold hid out at his mine . . . .

But old Sherman’s men didn’t come by our house . . . [and] caught my father instead

of my grandfather. They asked him where the gold was hid out. He told them he didn’t know.

But they thought he was just trying to save his gold. So they took him down to the creek . . .

and held him by the feet and pushed his head down under the water.

Then they’d jerk him up and ask again where the gold was. When he’d tell them he didn’t know –

which he didn’t – they’d push him down again. That went on several times. His weak lungs couldn’t

stand it. I reckon they just filled with water . . . But they did drown him . . . on Gill’s Creek.”

A letter which was written by Henry Belk’s uncle to Sarah Walkup Belk was her first news

of the tragedy. It read as follows:

“Sister Sarah, I have sad news to tell you. Abel, your husband and my brother, is I suppose

no more. He is not found as we know but there is a certain person buried about one and

a half miles below here, in Graham’s field, who I suppose is Abel. His clothes were like

those that Abel had on [and] Abel’s little mule is lying dead on the road not far from where

the man was drowned. [signed] Herron.”

It was a cheerless, somber day when Sarah Walkup Belk turned away from the red mound in old

Shiloh graveyard. But even darker were the thoughts that threatened to crush her, for everywhere

she seemed to sense the very presence of death.

Beyond the stones of the graveyard . . . lay fields bare and brown and dead, and there was little

promise anywhere that the resurrection of spring would provide adequate crops. The Confederacy,

too, she knew, was at its death and tired hungry hopeless men could no longer stem the rush

of advancing hordes from the north.

And now her husband was dead. What would she do now? Where would she turn?

How could she make a living for herself and her three babies? How actually to find enough food?

She went back to her farm and organized what poor efforts she could command. She found food

and clothing for herself, her babies and the Negroes. She managed to provide security in those

perilous days, joy even and much love. And always she taught her children. Sometimes it seemed

that doubt and despair would engulf her. Always when the darkness was heaviest the pinpoint of

a star broke through. She held to her faith. And she worked.

When the days were darkest she would repeat over and over again and in staunch faith the

prayer and prophecy of that day when without knowing it she had waved her last good-bye

to her young husband: “God will protect us; God will take care of us.”

(William Henry Belk, Merchant of the South, pp. 3-8)

Better to Die in the Last Ditch

“Twenty years after Appomattox in a survey to determine “how the war had most significantly changed”

the lives of Confederate women, all said that doing their own work or adjusting to hired Negro

domestics was their major postwar problem. Sallie Southall Cotton wrote to

General William G. LeDue in 1909 about Reconstruction:

“Defeated, oppressed, humiliated, poverty-stricken, disenfranchised, taxed to pay the war debt, while

too poor to support ourselves, deprived of opportunity politically, and handicapped by pride and the

bitterness of rebellion against our condition, the South was a pitiable spectacle – and her rise from

that condition to the splendid attainments of today is a crown of honor she deserves because she

has won it by overcoming obstacles which at first seemed insurmountable.”

Dr. Henry Bahnson, in his speech to Confederate veterans, had this to say about Confederate women:

“We can speak in unstilted praise of the best and greatest glory of the South – the women of the war.

Their soft voices inspired us, their prayers followed us and shielded us from temptation and harm.

We witnessed their Spartan courage and self-sacrifice in every stage of the war. We saw them send

their husbands and their fathers, their brothers and their sons and their sweethearts, to the front,

tempering their joy in the hour of triumph, cheering and comforting them in the days of despair and disaster.

Freely they gave of their abundance, and gladly endured privation and direct poverty that the men

in the field might be clothed and fed. Their days of unaccustomed toil were saddened with anxious

suspense, and the lonely, prayerful vigils of the night afforded no rest.

They nursed the sick and wounded; they soothed the dying; and in the last stages of the war when

all was lost but honor, were made to marvel at their saintly spirit of martyrdom standing as it were

almost neck deep in the desolation around tem, bravely facing their fate, while the light of heaven

illuminated their divinely beautiful countenances.”

Catherine DeRosset Meares [of Wilmington] remarked: “The sense of captivity, of subjugation . . .

[was] so galling that I cannot see how a manly spirit could submit to it . . . Oh, it is such degradation

to see [our] young men yield voluntary submission to these rascally Yankees. Better to stand on

the last plank and die in the last ditch.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, Volume II, Xlibris, 2011, pp. 1082-1083)

![]()

McDowell County, Winter, 1864:

"[We] took seats on the porch and waited an hour or two until the road and the house

[was clear of Yankee marauders] . . . the pantry was as bare as old Mother Hubbard’s . . .

Most of the meat had been taken out of the smoke-house, and what was left was thrown down

on the floor, and a barrel of vinegar poured over it and then covered with dust and ashes.

"It was some consolation that the next set [of marauders] that came along took this same meat

and ate it.” Mrs. [Emma] Rankin recalled that another group of northern soldiers came and demanded

the keys to the bureaus and drawers, but she told the first set of marauders had taken them. Not to

believe the ladies, the men broke down doors with axes to find them bare. The frightened little band

of civilians went to bed without supper.

Northern soldiers continued to straggle through the area . . . [and] upon finding that the home was

completely [devoid] of anything eatable or tote-able, a cavalryman rode up and told the ladies that he

would provide a guard because a squad of Negro soldiers would soon pass. Other troopers found

some liquor, got drunk, and caused havoc, threatening to shoot the ladies if they

didn’t produce their jewelry and watches.

This time a squad of fifty men came in and demanded the women cook for them. The ladies

said they had nothing to cook . . . [after the Yankees left the Dining Room, the ladies] discovered

the men had found a keg of cornmeal and sorghum. What they didn’t consume was smeared all

over the furniture and floor, then dusted it with cornmeal.

As the night drew near, the women locked themselves in the bedroom determined not to open the

door under any circumstances. They prepared themselves for another sleepless night. They could

hear the cavalry unhitch outside, then the clinking of spurs and sabers, and heavy boots come across

the porch, then up the steps . . . the men insisted they open the door, but the dispirited ladies kept quiet.

On one of the raids to the Carson family, a soldier had stolen the funeral shroud of an old slave

named Aunt Lucindy, a “king’s daughter” from Africa. “She was said to be over a hundred years old,

and had her shroud laid up in her “chist” for many years.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1117-1118)

![]()

“Dr. Archibald Henderson related a story told by his grandmother, Mrs. Sarah Cain. [Yankee cavalry]

in the vicinity of Asheville, rode their horses up on the porch of the Judge Bailey homestead as the

family was eating supper. The ruffians rifled through trunks and boxes, taking valuables, even the

rings from the women. Thomas Bailey went with the riders as their prisoner. The next day the troopers

returned to the site to kill the old judge. “Next morning several villainous-looking Yankees came and

took away the family’s supply of bacon. The judge was insulted on the street by a negro in blue uniform;

Mrs. Middleton literally fought with the Yankee soldiers in the effort to prevent them from stealing

her husband’s watch; and Mrs. James W. Patton . . . was choked almost to death by a Yankee

soldier who tore [her watch] from her . . . Negro troops under General Howley committed nameless

atrocities in the neighborhood of Asheville . . . Mrs. Patton and her sister were dragged

from their sick beds, their persons searched, and their valuables stolen.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1121-1122)

![]()

“The day was well-advanced. Granny had put on a ham to boil, and was making preparations

for her usual dinner. The boys were in the house when we saw a squad of blue uniforms running

across the hill. They troubled not about the gates, pulling the palings off the fence, they sped

across the garden in a bee line, and across the yard, as if for wager and until sunset there

were swarms of blue coats everywhere.

In less time than I can tell, the ham was jerked out of the pot, the pig [quartered] and carried

off on bayonets. All the meat was taken from the smoke house, store room rifled of peas and corn.

One drove after another [and filling] the house, going into every box and drawer and taking

all that was of value in their eyes.

They poured rice, and rye, our substitute for coffee, on the dining room floor and poured molasses

over the pile while flour was tracked from the barrels across the house.

We never saw our cow, calf, and half-grown heifer after that day . . . towards evening [hordes]

of men, looking more like wild beasts, began to pour in. [They had been at nearby William Horne’s

place, who] was hanged to make him tell where his valuables, money, etc. were concealed.

Mr. John P. MacLean was also hanged, and his house burned. Mr. Hamley [?] in the

same neighborhood was also dreadfully used that he died from the effects.

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1130-1131)

![]()

“After a walk of four miles we reached home . . . We were greeted by the news “they are

just shooting down cows all thro’ the woods, five or six are lying dead round the stable,

and you better see about Bella,” our fine cow hid in the swamp. I tried to get one of the

negro men to go down and bring her home, but not one of them would stir. They were “afraid

of the Yankees.” I told them that thus far I had shared what little we had with them, but now

they might look out for themselves, for I knew they were pretending, and even then preparing

to go join the colored refugees and go to Wilmington by boat.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pg. 1133)

![]()

Vengeance at Fayetteville

“That night the heavens were in a glow, the red light of fires in town. Tuesday they burned the

Arsenal and all the government property. The offices of the Fayetteville Observer and the

North Carolina Presbyterian, both of which had aided in keeping up “the arrant and rampart”

rebellion.” They were destroyed. Cotton factories, of which there were six or seven, and an iron

foundry, gristmills too, shared the same fate.

The Arsenal was battered down and fired. The armory machine shops, rifle factory, officers’

houses, subordinate officers quarters, barracks, etc. Dense columns of smoke covered the sky.

Falling walls, shouts of soldiers, music of the band, as if exulting in our overthrow, combined to

make it a dreadful day. [The] cinders fell in our yard, and garden; and people living nearer had to

make strenuous efforts to save their houses.

Sherman said he intended to leave a howling wilderness behind him. Hundreds of horses and cows

were shot, and left to putrefy in our midst. Carriages, wagons, and buggies were burned, every

means of subsistence in his track was destroyed.

The poor Negroes suffered. Never accustomed to [caring] for themselves, taking medicine by the

“house clock,” fed and clothed by the mistress, Granny never left her ‘white children” and died

some years after in her own room, tenderly cared for by them [white children].

Joe had two hens left, one sitting which hatched a full brood, all named after Yankees –

“because I wont mind killing them when they are grown.” Miss Sarah Ann Tillinghast

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1134-1135)

![]()

Sheer Hate, Cruelty and Wanton Destruction

“Sherman gave orders to his troops when he reached Fayetteville to destroy all property,

private and public, which would be of any use to the enemy; that he was going to wind up

the war. They destroyed our household furniture . . . His army destroyed literally every useful

thing, filling all the wells on the place with dead hogs, shooting the cows, and all other

living things, leaving what they did not want lying on the ground.

They rolled out barrels filled with the year’s supply of molasses, into the front hall, burst in the

heads, and let the molasses run on the floor, after which they brought quantities of rice, oats,

peas, meal, etc., and poured all of this on the molasses; then went up the stairs, cut the feather

beds and shook the feathers down on it, and then ran the horses over it, through the house. They

broke out all the window panes, broke doors and window blinds, cut up carpets

and made saddle blankets for their horses.

They killed every living thing on the place except the rats and dogs and carried off all

remaining year’s supply of food stuff. My parents and Negroes lived a few days on the

dead fowls. The Yankees moved my mother’s maid with her family, into the room adjoining

my mother’s bed-room thinking they would be humiliated living in the

same house with their former slaves.

These Negroes proved a blessing; they cooked for the Yankees and thus got food for my

parents, as long as the army was passing. [After] the main army passed, the stragglers

who followed put a rope around my father’s neck and were going to hang him, but did not,

as the Negro men interfered and drove them off.

My sister, with her two children, who were then living on the farm near Bentonville,

was left alone with her slaves, while her husband was with the home Guards. No one

ever expected Sherman to reach North Carolina by way of Bentonville, but were

looking for the Yankees to come from New Bern.”

This family was left only with the clothes they had on their body. Because the Federals had

poisoned the well with dead hogs, Negro women walked one-fourth of a mile to a stream for water.

She continued:

“After the battle of Bentonville my sister was left without food or protection. An officer in blue

advised her to take her two children and the two Negro women with her, and leave, as he could

not protect her . . . [they walked] four miles in the woods, just far enough from the Yankee

army not to be lost or discovered . . . She reached a neighbor [Mrs. Cogdel, whose wounded

Confederate son] was lying delirious with fever. [A] squad of Yankees, on horses, rode up,

taking her horses, and firing the house in several places.

My sister, Mrs. Cogdel, her daughter, and the servants carried her son out on a bed, to a field

near the house, and there saw the house burn down. Just after sunset, an officer in blue rode

up and asked what they were doing there. My sister replied, “To starve and die.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1146-1147)

“The Yankees had not been [to Mrs. Sarah Whitfield’s house yet], but while she was giving

her experiences [to us] a lot of them came. She did not live on the line of march, but these

men were stragglers from Sherman’s army which had passed on the way to Goldsboro the day before.

The old grandmother, 84 years old, lived with her daughter and granddaughter whose sons

were in Lee’s army. The deaf old woman had fallen a month before and was in bed with a broken hip.

The Yankees ordered her to get up, which she could not do, then one took her by the feet and

one took her shoulders, and tossed her across the room, going out, locking the door,

bidding none to go out or go in.”

A fire was burning in the fireplace but was getting low. The old lady begged not to let the

light go out. All the candles and lamps had been removed. The women in the room found

a box of paper patterns, tore these into thin strips and burned [them] till dawn.

“The Yankees destroyed almost everything except what was in their room and a small

quantity of provisions. My sister and the two Negroes stayed for a few days and then went

to my parents. They were riding army horses, bareback, the makeshift vehicle having been

destroyed by the last group of stragglers. When she reached home she found devastation and

sickness everywhere and the whole air was reeking with dead animals.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pp. 1146-1147)

![]()

“Catherine P. Peterson, with of Gibson Peterson, took an old slave named Tibb with her when she

married. Tibb stayed with the family after the war was over. When Sherman’s troops came through,

the family hid their valuables. The oldest boy hid the livestock in the swamps. The family hid a large

box of brown sugar under the dining room table, which had been constructed to conceal the box.

Mrs. Peterson tied the family’s silverware on strings and fastened them to her belt underneath her

hoop skirt [with each] wrapped in soft fabric.

The marauders stole the poultry, pigs, fodder and corn. Inside the home they stole molasses,

dried peaches and apples, tubs of lard, bags of onions, and strings of dried red peppers. One soldier

noticed that honeybees were flying in and under the table [and] discovered the sugar box.

Many families that had been stripped of every morsel of food, had to apply to the enemy for food after

the surrender. Catherine, with her servant Tibb, went to the Freedmen’s Bureau in Smithfield. Federal

authorities gave her scant portions of lard, cornmeal, molasses, and a few potatoes but no meat or flour.

She glanced around the room at all the meat piled up, probably portions stolen from her farm, and

asked for some. They refused, but did give some to Tibb who graciously shared.”

(Blood and War at My Doorstep, McKean, pg. 1155)

Another Family Made Homeless to Sherman’s Glory

Kentuckian Milford Overly wrote in 1904 his assessment of Sherman’s mostly unopposed march

from Atlanta to Bentonville: “It means murder, robbery, arson, and nearly all other crimes enumerated

in the black calendar, the details of which would shame vandalism itself.” He thought Sherman

a cruel one, “waging war with little less barbarity than did the savage chief whose name he bore.”

“The last act of barbarism I saw Sherman’s soldiers commit was near Bentonville, N.C., on the morning

of the last great battle for Southern independence. On the preceding night Gen. Joseph E. Johnston . . .

quietly moved his army from Smithfield and threw it directly across Sherman’s path at Bentonville.

Gen. George G. Dibrell’s cavalry division, composed of his own brigade of Tennesseans and

Col. Breckinridge’s Kentuckians, was falling back in front of one of the advancing Federal columns,

the writer of this commanding the rear guard, closely followed by the enemy’s advance.

We had just crossed a narrow swamp . . . and passed by a neat, comfortable-looking farmhouse,

occupied by women and children. Halting some distance beyond and looking back, we saw Federal

soldiers enter the house. Presently women were heard screaming, in a few minutes the building

was in flames, and another family was homeless.

Sherman’s raid was ended, and he was a great hero. With his great army of veterans, almost

unopposed, he had overrun and desolated the fairest sections of the South, burning cities, towns,

and country-dwellings; had wantonly destroyed many millions of dollars’ worth of property, both

public and private; had made homeless and destitute thousands of women and children and

aged men by burning their house and destroying their means of subsistence. And it was to

glorify him and for these deeds of barbarism that “Marching Through Georgia”

was written, and it is for this it is sung.”

(What Marching Through Georgia Means, Milford Overly, Confederate Veteran, September 1904, pg. 446)

![]()

When Sherman Came: Southern Women and the “Great March,” Katherine M. Jones, Bobbs-Merrill, 1964

The Wrights of Wilmington, Susan Block, Wilmington Printing Company, 1992

A Grandmother’s Recollection of Dixie, Mary Norcott Bryan, (1912), Dodo Press, 2010

Diary of Ada Amelia Costin, Wilmington, NC, May 21, 1861. Special Collections, Randall Library, UNC-W

Land of the Golden River, Volume 2 & 3, Lewis Philip Hall, Hall’s Enterprises, 1980

The Annals of Lincoln County, North Carolina, William L. Sherrill, Regional Publishing, 1972

Facts and Falsehoods, Concerning the War on the South, George Edmonds, Spence Hall Lamb, 1904

Inside the Confederate Government, The Diary of Robert Garlick Hill Kean, LSU Press, 1993

A Rebel’s Recollections, George Cary Eggleston, Indiana University Press, 1959

In The Country of the Enemy, Diary of a Massachusetts Corporal, University Press of Florida, 1999

Two Wars, General Samuel G. French, Confederate Veteran Publishing, 1901

Diary of Elizabeth Ellis Robeson, Bladen County, NC, 1847-1866, NC Division of Archives & History

The South in the Building of the Nation, Volume VII, Edwin Wiley, Southern Historical Publication Society, 1909

Story in Sampson Independent, February 1960; The Heritage of Sampson County (NC), Volume I, Oscar Bizzell, editor

General Robert F. Hoke, Lee’s Modest General, Daniel W. Barefoot, John F. Blair, 1996

William Henry Belk, Merchant of the South, LeGette Blythe, UNC Press, 1950

Back With The Tide, Memoirs of Ellen D. Bellamy, Bellamy Mansion Museum, 2002

Blood and War at My Doorstep, North Carolina Civilians in the WBTS, Brenda Chambers McKean, Volume II, Xlibris, 2011

True Tales of the South at War, How Soldiers Fought and Families Lived, 1861-1865, Clarence Poe, editor, Dover, 1995

What Marching Through Georgia Means, Milford Overly, Confederate Veteran, September 1904

Copyright 2013 The North Carolina War Between the States Commission