North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

The University of North Carolina:

A Powerful Influence and Presence

(Excerpted from the Centennial Celebration Address of Stephen Beauregard Weeks, June 5, 1895)

North Carolina Among the Heroic in History:

“The heroic in history but seldom occurs. It is not often that the life of nations rises above the

monotonous level which characterizes the daily routine of duty. When such periods do

occur they are usually a part of some great national uprising like the leve en masse

in France under the first Napoleon, or the Landsturm in Germany in 1813.

Of the American States, none can show a fairer record in this respect than North Carolina.

There is little in the Colonial or State history of North Carolina that is discreditable. The key-note

to the whole of her Colonial history is unending opposition to unjust and illegal government,

by whom and wherever exercised.

During the period from the end of the Revolution to the Civil War there are no mountain peaks

in her history; the level of uniformity is hardly broken by a single event of importance.

And there is little in it to attract the student of the philosophy of history.

But there is a period in the history of North Carolina which stands pre-eminent. There is a time

which deserves to be characterized as the Heroic Period of the State. This is the period

of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Let other parts of our history be forgotten,

this period of itself, though it be less than half a generation in all,

will place North Carolina among the heroic in history.

During those years we see a renaissance of the ideas which characterized pre-eminently

the men of the Colonial period. The men of ’61 showed that the spirit of Colonial North Carolina

was still abroad in the land, and their watchword became again resistance to what they believed

to be unjust government, and with this as a basis they conducted a struggle for success

that has few parallels in history. They sought again to

carry out the program of their colonial ancestors…..

In this movement that led up to the war North Carolina took the part of a conservative,

ambitious for peace. She sought to escape the necessity of war by all the means

in her power; but, when the die was cast and war was no longer avoidable, she entered

into the struggle with characteristic energy, and prosecute it to the end, and when

the end came, no State accepted the crushing defeat with more steadfast loyalty

than North Carolina, or sought with more energy to build up the waste places.

Then came what was worse than defeat…..the terrors of reconstruction….broke over us like

the roar of some terrible simoon, bearing in its path further humiliation, accompanied by

a corrupt government, increased taxes, and a depreciation of values.

Such was the struggle through which the best men of North Carolina were called to pass in

those fateful years between 1860 and 1875. These were the years on which the

fate of the future in a large measure depended.

Well did the brave men of that generation come to the succor of the foundering ship of State,

and nobly did they rescue her from the rule of her motley crew. The best men of North Carolina

were engaged in this work, and among them, most frequently as leaders, were many

alumni of the University of North Carolina.

University Men in Public Life

The first alumnus to attain the Governor’s chair was William Miller in 1814. Between this date

and the [military overthrow] of Governor [Zebulon] Vance in [1865], no less than fourteen out

of twenty governors were University men – Miller, Branch, Burton, Owen, Swain, Spaight,

Morehead, Graham, Manly, Winslow, Bragg, Ellis, Clark and Vance. They filled the

chair thirty-eight years out of the fifty-two.

The governor in 1861, John W. Ellis, and his opponent on the Whig ticket in 1860, John Pool,

were both alumni. The two Senators in Congress in 1861, Thomas Bragg and Thomas L.

Clingman; four of the Representatives in Congress, L. O’B. Branch, Thomas Ruffin, Z.B. Vance

and Warren Winslow, were University men.

The speakership of the State Senate, under Warren Winslow, W.W. Avery, Henry T. Clark,

Giles Mebane, M.E. Manly, and Tod R. Caldwell, was constantly under the direction of

University men between 1854 and 1870. With the exception of a period of fifteen years,

this office was continuously in the hands of University men between 1815 and 1870.

The members of the Supreme Court of the State, M.E. Manly, W.H. Battle, and R.M. Pearson,

were all alumni. Of the judges of the Superior Court in 1861, the University was represented by

John L. Bailey, Romulus M. Saunders, James W. Osborne, George Howard, Jr., and Thomas Ruffin, Jr.

In the same way four of the solicitors were University men, Elias C. Hines, Thomas Settle, Jr.,

Robert Strange, and David Coleman, and William Jenkins, the Attorney-General (1856-62),

made a fifth. All of his predecessors in the office of Attorney-General since 1810 had

been University men, except for those filling the position for a period of fourteen years.

Daniel W. Courts, State Treasurer (1852-63) was another alumnus, and so had been his

predecessors since 1837, except for two years. Three of the successful Breckinridge

[presidential] electors in 1860, John W. Moore, A.M. Scales and William B. Rodman, were alumni.

The list of the public officials will show conclusively that the large majority of the more important

positions in the State were filled by the alumni of the University.

They were the men controlling the destiny of the State in 1861.

Union Sentiment in North Carolina in 1861:

North Carolina was the last to enter the Confederacy, and her slowness was due, beyond question,

to the paramount influence exercised by the conservative views of the alumni of the University.

Willie P. Mangum, who had been the personal friend of the abolitionist Senator, William H. Seward

[of New York], when the latter first entered the United States Senate, had said in the Senate long

before, when the nullification of South Carolina was the topic of the day: “If I could coin my heart

into gold, and it were lawful in the sight of Heaven, I would pray God to give me firmness to

do it, to save the union from the fearful, the dreadful shock which I verily believe impends.”

His feelings were not changed by time, and in 1860 he said to his nephew who had been taught

in the school of Calhoun and Yancey, and now talked loudly of secession, that if he were an

emperor the nephew should be hanged for treason.

The Union sentiments of Governor Graham, Governor Morehead and Governor Vance,

and General Barringer, were just as pronounced as were those of Judge Mangum.

All of the old line Whigs opposed the war, while some of the Democrats, like

Bedford Brown, denied the right to secede.

Action of North Carolina General Assembly:

With such sentiments as these from her leading men it is hardly a matter of surprise

that North Carolina moved slowly in the consideration of this great question. On the

other hand, Judge S.J. Person, the leader of the secession forces in North Carolina,

was also a University man, and on December 10, 1860, as Chairman of the

Committee on Federal Relations, made a report to the General Assembly, in which it

was recommended that a convention be elected on February 7, 1861,

to meet on the 18th, to consider the grave situation.

A minority report was signed by three members of the committee, Giles Mebane,

Col. David Outlaw, and Nathan Newby, all University men, in which they opposed

the calling of a convention, on the ground that it was “premature and unnecessary.”

The conservatives carried their point and no [secession] convention was called.

During the month of January, 1861, various delegations were received from the more

Southern States which had already seceded. It was the duty of these commissioners

to bring North Carolina over, if possible, to the side of the Confederacy. The University

found three of her alumni among these commissioners: Isham W. Garrott from Alabama;

Jacob Thompson from Mississippi, and Samuel Hall from Georgia.

Jacob Thompson

[North Carolina] sent a delegation to meet similar delegations from other States

at Montgomery in February, 1861. The State sent a committee “for the purpose of

effecting an honorable and amicable adjustment of all the difficulties which

distract the country, upon the basis of the Crittenden resolutions,” and the parties

chosen were all University men: President D.L. Swain, General M.W. Ransom,

and Colonel John L. Bridgers.

In the same way three of the five commissioners sent by North Carolina to attend

the Peace Congress in Washington in 1861 [chaired by former President John Tyler]

were University men. They were J.M. Morehead, George Davis, and D.M. Barringer.

Finally, on January 30, 1861, through the strenuous efforts of Judge S.J. Person,

W.W. Avery, and Victor C. Barringer, all again University men, the Assembly of North

Carolina passed an act providing for the calling of a convention. The election was

on the 28th of February. In [W.W.] Holden’s paper, the Standard, of the 20th of March,

the official figures are given as 467 [votes] against a convention.

The same paper estimates that out of 93,000 votes cast at this election, 60,000

were in favor of the Union, and that 20,000 sympathizers with the same side staid

from the polls. Of the delegates elected about eighty-three were for the Union, and

only about thirty-seven for secession. No convention was therefore called and

secession was defeated for the second time in North Carolina.

The North Carolina Secession Convention:

The next and the inevitable step [after Lincoln’s attempt at reinforcing Fort Sumter and

call for 75,000 troops, some from North Carolina] was the Convention of 1861.

It was provided for by act of May 1; the election was held on May 13; on the 20th the

Convention met; on the same day, North Carolina, after much deliberation,

after a long consideration….passed the ordinance of secession. In this convention,

as elsewhere, University of North Carolina men were all powerful.

The Convention had….about 139 [members]. About one-third of these had been

students of this University [and] most of the leaders were University men.

When the convention came, on the 18th of June, to choose Senators and Representatives

from North Carolina to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, which

met in Richmond, in July 1861, the dominating influence of the University was

still more powerfully felt. Four men were nominated for the senatorships:

George Davis, W.W. Avery, Bedford Brown, and Henry W. Miller. They were all University men.

Davis and Avery were chosen.

For the eight seats in the Confederate House of Representatives, 17 candidates

were presented. Eight candidates were University men and four of these were

elected: Burton Craige, Thomas D. McDowell, John M. Morehead, and Thomas Ruffin, Jr.

Alumni in Confederate Executive Service:

John Manning was a receiver of the Confederate States. Jacob Thompson [of Leasburg]

was confidential agent to Canada. His object was to open communications with

secret organizations of anti-war men in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, to arrange for their

organization and arming so that they, when strong enough, might demand

a cessation of hostilities on the part of the Federal government. He acquired no little

notoriety in connection with the attempted release of Confederate prisoners from

Rock Island, Camp Chase, and Chicago….

Two sons of the University served as the head of the Confederate Department of Justice.

Thomas Bragg was the second and George Davis the fourth Attorney-General [of the Confederacy].

University Men in Military Service:

The highest rank held by a University man was that of Lieutenant-General. This was attained

by Leonidas Polk under a commission dated Oct. 10, 1862 [and] with one exception, the

only man to attain this rank without passing through the preliminary grade of Brigadier.

The University had only one other son to attain the rank of Major-General,

Bryan Grimes, commissioned Feb. 23, 1865.

Of Brigadier-Generals she had thirteen [George Burgwyn Anderson; Rufus Barringer,

Lawrence O’Bryan Branch, Thomas Lanier Clingman, Isham W. Garrott, Richard

Caswell Gatlin, Bryan Grimes, Robert Daniel Johnston, William Gaston Lewis,

James Johnston Pettigrew, Charles W. Phifer, Matt Whitaker

Ransom, and Alfred Moore Scales].

In the medical department we find Dr. Peter E. Hines as the Medical Director of

North Carolina troops, Dr. E. Burke Haywood as surgeon of the General Hospital

at Raleigh, and Joseph H. Baker was the first assistant surgeon of North Carolina troops….

Other alumni rendered similar service to other States; Ashby W. Spaight was

Brigadier-General in the service of Texas; Thomas C. Manning was Adjutant-General

of Louisiana in 1863, with the rank of Brigadier; Jacob Thompson was an Inspector-General.

When we come to the list of colonels and lieutenant-colonels their number is very large.

These were furnished to the Confederacy by North Carolina; seventy six regiments

(besides thirteen battalions and a few other troops, making, perhaps, in all

eighty full regiments). Out of the seventy-six regular regiments we find that forty-eight

had at one time or another a son of the University in the first or second place

of command. The list includes forty-five colonels and twenty-nine lieutenant-colonels….

[and] it seems that not less than sixty-three Alumni attained the rank of

colonel in the various regiments furnished by the different States to the

Confederacy, and that not less than thirty became lieutenant-colonels.”

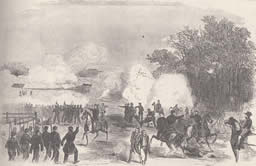

Chapel Hill:

[The] enthusiasm of patriotism] was not confined to the university. The residents

of Chapel Hill were among the earliest to enter the service. They had their representatives

at Bethel. A company was organized early in April [1861]. [Men from the Fourth

North Carolina District were] known as the Orange Light Infantry, and became

Company D of the First north Carolina, or Bethel Regiment, so called because of

its participation in the battle of Bethel.

Four companies were raised in Chapel Hill and vicinity during the war.

Company G, Eleventh North Carolina, was one of those companies that was made

up with volunteers from Chapel Hill and the surrounding regions of Orange,

with a few from Chatham county.”

The University faculty was not slower than the student body. Five of them

volunteered for the war. There were for the year 1860-61 five tutors in the University.

All of them volunteered. Four of them fell in the service. The total contributions of the

faculty past and present, of the University of North Carolina to the Confederate army

was fourteen, of whom seven, or fifty per cent, were killed.

Losses in the Field:

The University claims further, more than her proportion of the commanders of North Carolina

regiments that became distinguished because of their heavy losses in individual battles.

[The] 33rd North Carolina, under the command of C.M. Avery, met with a loss of [almost 42%]

at Chancellorsville; the 3rd North Carolina lost fifty per cent at Gettysburg; the 4th North Carolina

under G.B. Anderson, [over 54%] at Seven Pines; the 7th North Carolina , [56%] at Seven Days;

the 18th [North Carolina] under R.H. Cowan, [over 56%] at Seven Days;

the 1st North Carolina Battalion, under John D. Taylor, fifty-seven per cent at Bentonville;

the 27th North Carolina, [61%] at Sharpsburg; the 2nd North Carolina Battalion, [nearly 64%]

at Gettysburg; the 26th North Carolina, under H.K. Burgwyn,

[over 86%] at Gettysburg.

It will be seen that four of the nine regiments were under command of University

men at the time of meeting their heaviest losses.

The Sacrifice:

If we examine the records for the ten years before the war, we shall find that there

were 1331 matriculates between 1851 and 1860 inclusive; that out of these 1331 at least

759 or fifty-six and two-tenths per cent, saw service in the Confederate States army,

and they were in grades from private to brigadier-general.

Of the 759 that we know, 234 were killed. This means that thirty per cent of those

who went into the Confederate service from the University….sealed their faith with their

blood. The death rate is very near the average of the per cent of loss

sustained by North Carolina troops as a whole….”

Epilogue:

Saving always the fact that North Carolinians did not, as a rule, develop the peculiar

class of talent and character most highly esteemed by the President of the Confederacy,

it seems safe to say that no educational institution contributed more to the Confederacy

in proportion to relative strength than did the University of North Carolina.

[When] North Carolina saw, in May, 1861, that she had the choice between two evils and

that she could not remain neutral in the pending struggle, she made the choice that was

the most natural and reasonable. She chose the side of the State, or of local government,

against the growing tendency toward centralization then given

a new impulse by the Federal authorities.

The alumni of her University responded gladly to her call of duty. They were faithful to

the earlier teachings of their Alma Mater. They risked name and fame, life and fortune,

for their State. They laid down their lives at her command.

The names of our Confederate dead are carved in marble on our memorial walls,

but they have built themselves a monument more durable than marble. Their names are

written in lines of living light “On Fame’s Eternal camping-ground.”

The story of their heroism and their devotion to the call of duty will be cherished

by this University as the brightest jewel in her centennial crown, and their names

will be remembered in this institution as long as patriotism is honored here,

for “where deeds were done, A power abides transfused from sire to son.”

Confederate Veteran Alumni Reunion in 1910

(The Position of the University of North Carolina in 1861, Southern Historical Papers,

Vol. XXIV, R.A. Brock, editor, SHS, 1896. pp. 3-38)

Copyright 2012, North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission