North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

At War: Battlegrounds and the Homefront

The following paragraphs help us today in our understanding of North Carolinians at war 1861-1865, and bring us

an appreciation of the devotion to hearth, family and State they demonstrated so amply. Not simply a chronological

order of events and naming of various regiments and battles, the presentation below gives us many examples

and glimpses of the unsurpassed valor of North Carolina's soldiers who defended their State.

The Ranks Must be Filled:

"Old Thomas Carlton, of Burke county, was a good sample of the grand but unglorified class of men among us

who preserve the savor of good citizenship and ennoble humanity. He gave not only his goods to sustain

women and children, but gave all his sons, five in number, to the cause. One by one they fell, until at length a letter

arrived, telling that the youngest and last, the blue-eyed, fair-haired Benjamin of the hearth, had fallen also. When

made aware of his desolation, he made no complaint, uttered no exclamation of heart-broken despair, but called

his son-in-law, a delicate, feeble man, who had been discharged by the surgeons, and said, whilst his frail body

trembled with emotion and tears ran down his cheeks,

"Get your knapsack William, the ranks must be filled!"

Bethel:

“This battle [Bethel]…was fought on the 10th of June, 1861. Being the first serious fight of the war…

Col. D.H. Hill had, with the First North Carolina regiment, thrown up an enclosed earthwork on the bank

of Marsh creek. The Confederate position was held by the following forces: Three companies of the Third Virginia,

under Lieut.-Col. W.D. Stuart…three companies of the Virginia battalion, under Maj. E.B. Montague;

five pieces of artillery, under Maj. (afterward secretary of war) G.W. Randolph, of the Richmond Howitzers;

and the First North Carolina, under Colonel Hill.

The companies composing the North Carolina regiment, which had the envied distinction of being the initial

troops to enter organized battle, were: Edgecombe Guards, Capt. J.L. Bridgers; Hornet’s Nest Riflemen (Mecklenburg),

Capt. L.S. Williams; Charlotte Grays, Capt. E.A. Ross; Orange Light Infantry, Capt. R.J. Ashe; Buncombe Rifles,

Capt. William McDowell; Lafayette Light Infantry (Cumberland), Capt. J.B. Starr; Burke Rifles, Capt. C.M. Avery;

Fayetteville Light Infantry, Capt. Wright Huske; Enfield Blues, Capt. D.B. Bell; Southern Stars (Lincoln), Capt. W.J. Hoke.

The whole force was nominally under the command of Col. J.B. Magruder, and numbered between 1,200 and 1,400 men.

(The Northern attack] was repelled mainly by [Major] Randolph’s accurate fire, aided by the gallant conduct of the

Burke Rifles under Captain Avery and by the Hornet’s Nest Rifles. A little late in the action the Edgecombe Guards,

Captain Bridgers, gallantly retook a redoubt that had, on the accidental disabling of a gun, been abandoned by

the Confederates. In front of this redoubt the Federals had found shelter behind and in a house.

Colonel Hill called for volunteers from the Edgecombe guards to burn this house. Sergt. George H. Williams,

Thomas Fallon, John H. Thorpe, H.L. Wyatt, and R.H. Bradley promptly offered their services and made a brave

rush for the house. On the way a shot from the enemy’s rear guard struck Wyatt down. The determined spirit of

this heroic young soldier led to a premature death, but by dying he won the undying fame of being the first

Confederate soldier killed in action.

An attempt to turn the Confederate left having failed, [the Northern] forces retreated toward Fortress Monroe.

The Confederate loss in this precursor of many bloody fields was 1 killed and 11 wounded; the Federal loss was

18 killed and 53 wounded. In the South this little victory over a vastly superior force awakened the wildest enthusiasm,

for it was thought to indicate the future and final success of the cause for which its people were battling.”

(Confederate Military History, D.H. Hill, Jr., pp. 17-20)

Fleeting Moments of Loving Ministry:

“In 1861, Greensboro was a peaceful hamlet of about 2,000 souls, but when the tocsin of war sounded

at Sumter, the Revolutionary blood in the veins of our people leaped into instant action. In the dark time

of infinite endurance that followed, the women suffered and shared the fears and hopes of the impending battles,

the harrowing days, the hopeless nights, the dread to-morrows.

The noble army of the Red Cross had not then unfurled its banner to the world, and the unspeakable blessing

of hospitals and trained nurses was as yet unknown. More pitiful was the lack of anesthetics. Yet in this

painful lack of equipment, the self-sacrifice, the ingenuity, and faithful service of our women made what

amends were possible.

A central room was established where quilting and sewing were daily and diligently done. Every piece of old

linen was scraped and cherished, bandages made, carpets taken up; and all blankets, clothing, food, and

whatever could be given up for the comfort of the boys were sent to the camps. A little amateur band of canteen

workers met the trains bearing the wounded, often in the darkness of night, with such refreshments as they could

provide for the weary men, and in these fleeting moments of loving ministry precious items of news from home

and camp and friends were eagerly sought and given ere the train sped on.

Weary, footsore, and needy soldiers were daily passing through to be clothed, fed, and comforted; and

whenever the Danville train came in with grey-coats on board, it was a signal to broil bacon, bake cornbread,

and set out all the milk one could lay their hands on – the only delicacies we could then afford.

In this labor of love all our hearts were sore with suspense and foreboding for husbands, sons, and brothers

on the firing line, not knowing what a day or even an hour might bring forth; and many homes were darkened

as the casualties fell pitilessly here and there.”

(The Women of the South in War Times, pp. 230-231)

First Manassas:

"The six weeks that intervened between Bethel and First Manassas were weeks of ceaseless activity.

Regiments marched and countermarched; North Carolina was hardly more than one big camp, quivering with

excitement, bustling with energy, overflowing with patriotic ardor. The Confederate army under Generals Johnston

and Beauregard was throwing itself into positon to stop the "On to Richmond" march of the Federal army under

General Irvin McDowell. In this great battle, so signally victorious for the Confederate arms, North Carolina had fewer

troops engaged than it had in any other important battle of the armies in Virginia.

Col. W.W. Kirkland's Eleventh (afterward Twenty-first) regiment, with two companies -- Captain Conolly's

and Captain Wharton's -- atttached, and the Fifth, Lieut.-Col. J.P. jones in command during the sickness of

Colonel McRae, were present, but so situated that they took no part in the engagement.

The Sixth [North Carolina] was hotly engaged, however, and lost its gallant colonel, Charles F. Fisher

[Fort Fisher on the Cape Fear would be named for him]. When this regiment arrived at Manassas Junction,

the battle was already raging. Colonel Fisher moved his regiment forward entirely under cover until he reached

an open field leading up to the famous Henry house plateau, Fisher's presence was not even suspected by the

enemy until he broke cover...and with commendable gallantry, but with lamentable inexperience, cried out to his

regiment, which was then moving by flank and not in line of battle, "Follow me," and moved directly toward the

[enemy artillery] guns.

At this juncture Capt. I.E. Avery said to his courageous colonel, who was also his close

friend, "Now we ought to charge." "That is right captain," answered Fisher, and his loud command,

"Charge!" was the last word his loved regiment heard from his lips. In prompt obedience the seven

companies rushed up to the guns, whose officers fought them until their men were nearly all cut down

and their commander seriously wounded. But the charge was a costly one. Colonel Fisher, in the words

of General Beauregard, "fell after soldierly behavior at the head of his regiment with ranks greatly thinned."

With him went down many North Carolinians "whose names were not so prominent,

but whose conduct was as heroic."

One of the companies composing the Sixth came from Rowan county, and Colonel Fisher himself had long

been a conspicuous citizen of Salisbury. From 1851 Fisher had been convinced that secession was inevitable,

and after the election of Lincoln he had begun the organization of a volunteer regiment among the young men in

the western part of the State, particularly in the counties adjacent to the North Carolina Railroad. The Sixth Regiment,

equipped from Fisher's private purse, left its training camp in North Carolina on July 10, and had been at the "front"

barely ten days when fate assigned its commander a rendezvous with death. Charles Frederick Fisher was an eminent

figure in State politics during the first half of the century, and had been editor of the Western Carolinian at Salisbury

and in 1855 had succeeded John M. Morehead as president of the North Carolina Railroad.

The Sixth lost 73 men in killed and wounded. This battle ended the fighting in Virginia for that year [1861].

North Carolina, however, was not so fortunate, for the next month saw [Northern forces descend] upon its coast."

(Confederate Military History, D.H. Hill, Jr., pp. 21-23)

Mrs. Armand DeRossett: The Soldier's Angel of Mercy:

"The North Carolina coast was especially inviting to the attacks of the enemy, and Mrs. DeRosset’s

household was removed to the interior of the State. Her beautiful home in Wilmington was despoiled largely

of its belongings; servants and children were taken away, but she soon returned to Wilmington...and she devoted

herself to the work of helping and comforting the soldiers.

Six of her own sons and three sons-in-law wore the grey. The first work was to make clothing for the men.

Many a poor fellow was soon without a change of clothing. Large supplies were made and kept on hand.

Haversacks were home-made. Canteens were covered. Cartridges for rifles, and powder bags for the great

Columbiads were made by hundreds. Canvas bags to be filled with sand and used on the fortifications, were

largely used at Fort Fisher – and much more was in requisition.

The ladies would daily gather at the City Hall and ply their busy needles or machines, with never a sigh of weariness.

When troops were being massed in Virginia, Wilmington, being the principal port of entry for the Confederacy,

was naturally an advantageous point for obtaining supplies through the blockade, and Mrs. DeRosset, ever watching

the opportunity to secure them, had a large room in her dwelling fitted up as a store room. Many a veteran in these

intervening years has blessed the memory of Mrs. DeRosset and her faithful [aides] for the comfort and refreshment

so lavishly bestowed upon him. Feasts without price were constantly spread at the depot. Nor were their spiritual

needs neglected. Bibles, prayer books and hymn books were distributed.

Men still live [1895] who treasure their war Bible among their most valued possessions."

(Confederate Veteran, July, 1895, pp. 218-219)

Fighting Along the Coast:

"On its secession the State undertook the protection of its long coast line by the erection of forts at [the]

inlets and by the establishment of a fleet of small vessels fitted by their shallow draft to defend the waters

of the sounds. To lighten the load of the governor in this time of intense activity, the legislature, not profitting

by the failure of the Board of War during the Revolution, created a similar body known as the Military and Naval Board.

This Board, consisting of Warren Winslow, Military Secretary, and Chairman, James A.J. Bradford, and

Haywood W. Guion, took over most of the military activities of the State, including the coast defenses.

Under the direction of the Board two departments of coast defenses were established. The northern, extending from

Norfolk to New River in Onslow County, was put under the command of Brigadier-General Walter Gwynn; the

southern comprising the sea front from New River to South Carolina, was committed to Brigadier-General Theophilus

H. Holmes, who had recently resigned his commission as major in the United States Army and offered his

services to North Carolina, his native State. THese two officers, both of course acting at that time only

under State commissions, entered on their duties on May 27, 1861.

Just a month later, however, all the forts in process of building, together with those already existing, namely,

Fort Caswell and Fort Johnston near Wilmington, and Fort Macon at Beaufort Inlet, were ceded to the

Confederate government, but the transfer of property and troops was not completed until about the middle of August.

Forts were built at Hatteras, six miles from the stormy cape; at Oregon Inlet just south of Roanoke Island;

at Ocracoke Inlet, about thirty miles below Hatteras Inlet; and the formidable Fort Fisher, near Wilmington,

was begun. The three forts already existing -- Fort Macon, guarding the harbor of Beaufort, and Forts Caswell

and Johnston protecting Wilmington, were strengthened, but could not be either adequately armed or fully manned.

An attempt to have the State man its own seaboard fortifications was made shortly after North Carolina

withdrew from the Union. R.H. Smith, of Halifax County, introduced in the convention on May 28 an ordinance

to raise seven regiments of troops to be used exclusively for coastal protection. [Governor John W. Ellis] said:

"If the batteries are properly served, a fact of which I could entertain no doubt, the power of the

United States navy is not sufficient to effect an entrance into any one of these forts."

(Bethel to Sharpsburg, pp. 155-157)

From Roanoke Island to New Bern:

“Roanoke island, said the Raleigh Standard in October [1861], “is an important strategic point for the protection

of the region bordering upon Albemarle Sound, and to check any rear movement of the enemy against Norfolk.

It is, therefore, of great importance that the eyes of President [Jefferson] Davis and Governor [Henry Toole] Clark

should be directed to that point. The intimations from the North are strong that the enemy will soon attempt to

assail Roanoke island with a strong force from Hatteras.”

Early in January came reports that a fleet with many transports had sailed for Hatteras….[and] the New York Times

thought it was a matter of easy conjecture that its objective was the North Carolina forts on the Pamlico and

Albemarle sounds. The troops and the defensive equipment supplied to the forts at Roanoke island and at New Bern

were no match for the 15,000 Northern soldiers and the heavy ordnance carried on their gunboats. The defenders

comprised about 1435 men of the Eighth and Thirty-first North Carolina Regiments, assisted by the Forty-fifth

and Fifty-ninth Virginia Regiments. On the North Carolinians breastworks were smooth-bore cannon little superior

to the type used in the Revolution against the British. One regiment was armed with squirrel rifles and shotguns

and the best trained of North Carolina troops were in Virginia.

The battle of Roanoke island began on February 7, 1862. The small North Carolina fleet, commanded by

William F. Lynch, after using up all its ammunition had to retire. Northern troops were landed and the defenders were

compelled to surrender. In a few days the Northern fleet and troops raided as far as Elizabeth City, Edenton and

Winton, they burned the latter.

The next point of attack was New Bern, where General L. O’B. Branch [of Enfield, North Carolina] had less than

5,000 men against the formidable array of Northern ships and soldiers. The battle of New Bern was fought on March 14,

and despite the valor displayed by Col. Zeb Vance’s Twenty-sixth North Carolina Regiment and one or two other

units, Gen. O’B. Branch ordered a retreat to Kinston. New Bern was left to its fate.

No one but Negroes and “poor whites” were around to greet the victors. The Negroes, “hilarious in the employment

of their newly found “Uncle Sam,” were holding “a grand jubilee.” While some “in their rude way” thanked God

for their deliverance, others danced in “wild delight” and sang, and still others, “with an eye to their main chance,”

were pillaging the stores and dwellings.

The Northern soldiers and sailors soon joined the Negroes in these acts of lawlessness, and for a day or two after

its capture, New Bern was pillaged with no restraint. Northern General Burnside selected a stately old home in

New Bern for his headquarters, but when an aide went to get the home in order, he found it in the process of being

plundered by soldiers, sailors, and Negroes. One old Negro was trying his best to make off with all the china ware.

Only the threat of putting the vandals in irons got them out of the house.

The people of North Carolina were shocked and angry at the apparently easy conquest of New Bern. [And] as a

result of these successive defeats, North Carolina people, declared Gen. D.H. Hill, “saw plainly that the Richmond

authorities had been far too slow in realizing the State’s condition and the importance of the territory being lost.”

The effect, however, was to stimulate new exertions for home defense, and within a short time fifteen

regiments had been organized.”

(North Carolina, The Old North State and the New, Vol. II, pp. 230-231)

The Pillage of New Bern:

“For a day or two after its capture the town with its neighboring country was pillaged without restraint.

“The soldiers and sailors had free run in New Bern the first twenty-four hours,” writes Putnam,

a member of the Twenty-fifth Massachusetts Regiment. Everything that the soldiers wanted and much

that they did not want was taken from the defenseless homes. During the remaining years of the war the

Federal pillaging of Eastern North Carolina was so unrestrained and so shameless that a writer of this

generation has no heart to recount its sickening details.

Captain Thomas H. Parker of the Fifty-first Pennsylvania Regiment [wrote]: “All the large plantations

throughout the South have vaults or graveyards close to the mansion…a vault on this place, close to

the dwelling house and within 50 yards of the Trent river, contained a large number of coffins with remains

of members of the family for several generations back, but a visit to the place by members of a Connecticut

and a New York regiment, soon reduced the structure to a shapeless collection of ruins, having

burst the cerements of the departed and piled the bones in a confused mass…All the property in this

region was abandoned…and the places left to the ruthless mercy of the Yankee army…”

(Bethel to Sharpsburg, pp. 235-237)

Refugeeing in North Carolina:

The port city of Wilmington, guarded by Fort Fisher until early 1865, was a refugee center.

Those in search of commercial opportunities, employment, or passage to a foreign country flocked to the city,

but never were hundreds banished from Northern lines dumped on the city at one time as in the case of Charleston,

Savannah and Mobile. Refugees came from all areas of the Confederacy -- James Ryder Randall was surprised to find

several New Orleans families living in his boardinghouse. These, he said, "were birds of passage" who hoped to

get to Nassau. Although Wilmington was crowded throughout the war, hundreds of people in flight before Sherman

arrived in its last months. A local citizen referred to this last influx as "the most serious difficulty we have had to

contend with," and she estimated that "thousands...[representing] all classes and grades...[came] from all directions,"

and were being "put in every nook and corner" of the city. Although many Wilmington citizens moved to the

interior of the State, the greatest single evacuation was not the enemy but the yellow fever epidemic [of Fall, 1862]."

(Refugee Life in the Confederacy, page 78)

The Peninsular Campaign:

Caldwell County’s “Little Rebel”:

“For all the hardships on the home front, support for the war was still strong enough in the

spring of 1862 to allow the original companies raised in Caldwell to easily refill their ranks. Avoidance

of the stigma of being drafted and the desire to bond with friends and relatives who had been the first

to enlist played a major role in drawing older men into the army.

But at least as important was the fear of being seen as an effeminate coward by the young women,

nearly all of whom were impassioned Confederates. In addition to sewing and weaving clothes for the

troops and sending off packages of food, household items, and bandages, young women served as

the Confederate army’s most effective recruiters.

Laura Norwood, [Walter Lenoir’s] twenty-one year niece, took pride in referring to herself as a “little rebel.”

She was among the young women who presented a company flag to the Caldwell Rough and Readys

when they left Lenoir for the war. Writing Walter in April 1862, she assured him that “never will I be defeated,

never, under the Sun!” For her and countless other young women, the war was a heroic adventure in which

the “generous, the brave, the self-denying, self-forgetting, the fearless, the true-hearted, the daring, the

unyielding to temptation, in a word the True!” risked all in the defense of country and loved ones. She need

hardly have added that no coward could ever claim her love.

[Other Southern women] found reason enough to steel themselves when the read or heard of

Yankee atrocities committed on Southern soil. Unlike Laura, Walter’s sister Sarah was a reluctant

Confederate at the onset of what she called this “cruel war.” But her nephew Nathan Gwynn, home

recuperating from a wound in the winter of 1862, convinced her of the need to endure whatever sacrifices

were called for. “It makes my heart ache and my blood boil to hear Nathan tell about those Yankees!”

she wrote Walter. “I could not believe the newspapers! But I have to believe him! Surely our army would

not do so, in the Northern States. They would not harm the women and children and destroy the churches.!”

(The Making of a Confederate, pp. 69-70)

Methodist Clergyman Joel W. Tucker of Fayetteville:

"In quick succession he gave three sermons that were published and distributed throughout the South as

comforting, if stern, theological interpretations of the place of the Confederacy in divine history. In one of

the sermons, "God's Providence in War," delivered to his congregation in Fayetteville on Friday, 16 May 1862,

a general fast day, Tucker saw the ongoing war as "a conflict of truth with error -- of the Bible with

Northern infidelity -- of pure Christianity with Northern fanaticism -- of liberty with despotism -- of right with might."

In the next, "God Sovereign and Man Free" (1862), he prayed "for the success of our cause; for the triumph

of our armies," arguing that God could "answer our petitions, because he has sovereign control over of the

bodies and souls of men." These two sermons expressed succinctly and clearly the epitome of Southern

wartime religious ideology, making Tucker momentarily one of the most popular and lauded

prophets of the wartime South.

The third published sermon, "Guilt and Punishment of Extortion," preached on 7 September 1862, was

directed at the extortioners who caused serious price inflation and contributed to the scarcity of certain goods.

(Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, Vol. 6, page 58)

The Struggle for Richmond, 1862:

After the Seven Days Battle:

“In late June [1862], Walter [Lenoir] took a break from his camp duties and went to Richmond to confer

with [Zebulon] Vance on the disposition of the men in his Caldwell [county] company. There he had a chance

to walk over the sites of the Seven Days Battles, where thousands of Confederate troops had successfully

defended Richmond against General George B. McClellan’s massive Union army. The signs of combat

were still fresh and raw when Walter visited on June 30, picking up spent bullets, Yankee cartridges,

and other battlefield detritus as souvenirs for [his brother] Rufus.

He was struck by the incongruity of seeing so many dead and dying soldiers covering placid

farm fields: “To the eye they were fields with the fences down, and crops less interfered with than you

would have supposed, and fresh graves and dead men & horses lying in the sun here and there, all over them.”

When he returned a few days later to sites he had already visited, he observed that many of the Yankee

dead were still unburied. One poor soul, a wounded Yankee whom Walter had seen on Monday,

was still there on Friday, “dying but not yet dead.” By then, the Confederate dead had found

a resting place in shallow graves dug where they fell, their names inscribed on crude pieces of

planking placed at the head of their graves.

Unless the bodies were removed to a new burial site and more permanent markings erected,

the identity of the fallen would be forever lost, he mused. “They fell fighting as heroes and patriots fight,”

he wrote Rufus, “and they will be remembered and thought of with love & regret at home, long after

their memory would have been forgotten if they had lived in inglorious ease at home."

(The Making of a Confederate, Walter Lenoir, pp. 72-73

Second Manassas:

“North Carolina had eleven regiments and one battalion of infantry and two batteries of artillery engaged…

In [General Evander] Law’s brigade was the Sixth regiment, Major R.F. Webb; in [General Isaac] Trimble’s, the

Twenty-first and First battalion; in [General Laurence O’B.] Branch’s brigade, the Seventh, Captain R.B. MacRae;

the Eighteenth, Lt. Colonel Purdie; the Twenty-eighth, Colonel J.H. Lane; the Thirty-third, Lt. Colonel R.F. Hoke, and

the Thirty-seventh, Lt. Colonel W.M. Barbour; In [General William D.] Pender’s brigade, the Sixteenth,

Captain L.W. Stowe; the Twenty-second, Major C.C. Cole; the Thirty-fourth, Colonel R.H. Riddick, and the

Thirty-eighth, Captain McLaughlin; Latham’s battery, Lt. J.R. Potts, and Reilly’s battery, Captain James Reilly.

On the morning of the 30th [July, the Northern commander] massed [his troops] in a final effort to crush

[General Stonewall] Jackson. Straightaway…Reilly’s North Carolina battery…opened a destructive enfilade

fire on Jackson’s assailants. “It was a fire that no troops could live under for ten minutes,” is [General James]

Longstreet’s characterization of the work done by these batteries, soon added to by all of Col. [Stephen Dill] Lee’s guns.

The Federal lines crumbled into disorder from the double fire, but again and again they stoutly reformed, only at

last to be discomfited. For the possession of the Henry house hill, so vital to the Federal retreat, both sides fiercely

contested, and the dead lay thick on its sides. General Law reports that he united the Sixth North Carolina with his

other regiments in a charge on a destructive battery near the Dugan house, and drove the gunners from it.

Latham’s and Reilly’s batteries contributed their full share to this victory. Col. R.H. Riddick, whose power as a

disciplinarian and ability as a field officer had made the Thirty-fourth North Carolina so efficient, was mortally

wounded there, as was Major Eli H. Miller, and Captain Stowe, commanding the Sixteenth North Carolina. The

North Carolina losses in the two days and one night at Manassas were as follows: killed, 70; wounded 448.

At Ox Hill, or Chantilly, they were: killed, 29; wounded, 139.”

(Confederate Military History, pp. 99-104)

Captain Walter Lenoir at Cedar Mountain and Ox Hill:

“[On July 23, [1862] Walter W. Lenoir of Caldwell county learned] he had been elected and appointed first

Lieutenant of Company A in the 37th North Carolina regiment. On the way to Richmond, Walter learned that

the captain of Company A had resigned on account of bad health, and he had been promoted to take the

captain’s place. The news left him with a heavy sense of responsibility, for he was now asked to command

battle-hardened veterans.

Walter’s regiment had been in camp near Gordonsville [Virginia] for only a few days when it received

marching orders on August 6. [Despite stomach problems]…he found himself relishing the nightly fare

of dry army crackers, cakes of flour heated on strips of wood over an open fire, badly cooked beef

roasted on sticks, and raw bacon.

After a few days he and his men were filthy and covered with body lice, an indignity Walter blamed

on the abandoned Yankee knapsacks they found on the outskirts of Richmond. Since learning that

he would be serving in General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s corps, Walter had always expected

to be sent “to some place where there is good work to be done.” That place was Cedar Mountain.

Walter’s company had about an hour to rest before it was thrown into the battle to fill the gap in the

Confederate lines. The thought of dying, but not of being wounded, ran through his mind. Most of his men,

he observed, became serious as they awaited battle, yet once in action they seemed to possess an

amazing ability to cast aside their fear of death and face with cool indifference the awful sights and

sounds that would envelop them.

The battle enveloped Walter in a bedlam of noise and confusion as the retreating Virginians swarmed

through the Confederate lines, separating him from some of the men in his company …[but able to keep]

the remnant of his company moving forward only by constant effort. After repulsing a Union cavalry charge

(“in almost an instant eight or ten dead horses were piled in the road”), the Confederates charged…

across the cornfield to attack the fleeing Yankees, but they quickly fell back to a safe position.

After praising his men for their bravery and checking on casualties and those present for duty,

Walter joined other Confederates in roaming over the battlefield. The Yankees had been badly bloodied;

Walter stepped over the bodies of at least six or eight of their dead. Yet no one had been killed

or wounded in Walter’s company and casualties in his regiment were very light. He could find no

explanation for the contrast “except that our God in whom we trust favored our righteous cause.”

[Resting on a slight ridge after the Ox Hill engagement of August 31, Walter] felt an “awful pain” in his right leg.

A minie ball had ripped through it about halfway between his knee and foot, smashing both bones. No

sooner had he told [Captain] Morris that he thought his leg had been broken when a second ball, perhaps

skipping up from the ground, laid bare the shinbone in the same leg and took off his right toe.

Disabled and fearing that he would bleed to death from a severed artery, he began to drag himself toward

the rear…[and] Exhausted after crawling for about fifteen feet, he collapsed in a small clearing by the road.

As sand was thrown into his face by minie balls striking the ground near his head and Yankee artillery

shells exploded all around him, he realized he was in a more exposed position than the fence he had just left.

He lay hopeless, waiting to die.

Looking back, Walter marveled at how calm and resigned he had felt. What sustained him was faith

in the God he never had acknowledged in a public confession of faith. He felt that he was “in the hands

of a good and merciful God and that He would do with me what was right.”

(The Making of a Confederate, pp. 77-88)

Sharpsburg:

“On Tuesday, September 16 [1862], the prelude to the main battle at Sharpsburg began.

General McClellan had pushed the remained of [General Robert E.] Lee’s army through the gaps of

South Mountain to a point near Antietam Creek, where he hoped to trap and destroy the Confederates.

Major James T. Reilly

The Rowan Artillery [of Major James T. Reilly] joined the action at ten o’clock. Two sections of rifled guns,

composed of two three-inch rifles commanded by Lieutenant [Jesse] F. Woodard [of Wayne county]

and two ten-pound Parrott rifles commanded by Lieutenant [John A.] Ramsay [of Iredell county], received

orders to engage the enemy and maintain a steady well-directed fire until ordered to redeploy. After

expending four hundred and eighty-four rounds of ammunition and with two horses killed and one

wounded and abandoned, the battery was ordered to retire to the rear,

refill their ammunition chests and encamp.

Early in the morning, the battery’s two rifled sections proceeded with the rest of Major

[Bushrod Washington] Frobel’s Battalion to oppose the Union advance from the cornfield and around

the Dunkard Church. Reilly’s Battery fired into the enemy with devastation effect until their ammunition

was exhausted…During [the Antietam Creek bridge] assault, the howitzer section of the

Rowan Artillery suffered greatly from [Northern] massed artillery fire. All their horses were killed and they

had to draw theirguns back to safety to avoid capture. One gun was totally disabled; three men were killed,

two wounded and two missing.

More than five hundred cannons participated in the battle, firing over fifty thousand rounds of ammunition.

The cannonading was so intense that Confederate artillery commander, Colonel S.D. Lee, called it “artillery hell.”

The psychological effects and confusion were overwhelming. Extreme noise levels of the guns, exploding

of case and shot overhead and the agonizing screams of men being wounded and killed were deafening.

The odor of fresh flesh being torn from bodies and the putrid smell of flesh left to rot assaulted the senses.

Horrible sights and sounds included horses killed and wounded, struggling to escape without legs and

eyes as large as saucers from fear and panic.

General A.P. Hill’s arrival from Harper’s Ferry saved the Army of Northern Virginia in a nick of time.

Hill smashed into [the Northern] left flank, driving [them] back. This day, September 17, 1862, was

the bloodiest single day in American history with a total of twenty-three thousand men killed or wounded.

The day after the Battle of Sharpsburg the men of Reilly’s Battery were commanded to “trot march,” but

did not obey. The men and horses were “give out,” having been on the field of battle four days, the last

two and a half without rations.”

(Men of God, Angels of Death” pp. 54-57)

Battles in North Carolina:

Garrison Life on the Coast:

"It is difficult to imagine what life must have been like for the four hundred to eight hundred Confederate soldiers

[mostly North Carolinans] who were garrisoned at Fort Caswell during this war. Letters written to friends and

family memebrs bring the Twentieth Century viewer closer to their experiences and feelings than any other medium.

Letters Home:

"We have to cook for ourselves...You would laugh if you could be here about eating time, and see th soldiers

scrambling for something to eat. We have plenty to eat though you must know it is badly cooked."

(Lily, April 17, 1861)

"The weather is "absolutely hot. Hot enough to cook eggs if we had any of that article down here."

The soldiers speend the rest of their days lounging "about in the shade when we can find anything like

a shade (tree), there is no trees you must recolect (sic) and when night comes instead of getting cooler it

positively gets warmer and the mosquitoes come in swarms...Some of them (are) as large as humming birds

with bills half an inch long. So that with the heat and the mosquitoes there is no such thing as sleeping."

(McNeil, August 18, 1862).

Christmas, 1862 -- "We had turnips, Beef and Bacon for dinner which was good enough for supper. Oyster

soup which was better." (McNeil, January 4, 1863)

"Please send the following articles -- 1 or 2 hams (one boiled, the other raw) as much sausage as you can

spare, two or three bottles of catsup, as much butter as you can get well salted, two or three heads of cabbage,

some biscuit as many as you want to cook for those you cooked for me before I left home are better today

than the bread cooked here. Please send a bill of the things giving the market rates at home; for I must make

a report at the end of the month to the mess and will get pay or something else to eat in return for it."

(Turrentine, February 2, 1863)

Christmas 1863 -- "My mess had a very fine dinner -- for a sample, we had chicken, turkey, spunge (sic)

cakepound cake and a great many other kinds of cakes." (Duie, December 27, 1863)

(Fort Caswell in War and Peace, pp. 34-36)

Postwar Fort Caswell

Lincoln's Proconsul in Occupied New Bern:

"It was Lincoln's policy to "restore" disaffected States or parts of States to the [Northern] Union whenever

possible. In April, 1862, secretary of war Stanton announced the appointment of [North Carolina native]

Edward Stanly as military governor of North Carolina. He was a Whig, devoted to the Union, and on going

to California about 1856 had affilliated himself with the Republican party of that State.

He was quick to comprehend the difficulty in reconciling the population to the Lincoln administration. From

New Bern on June 12, in a letter to Secretary Stanton, he said..."Unless I can give them some assurance

that this is a war of restoration, and not of abolition and destruction, no peace can be restored here for

many years to come." Protesting against...the "shameless pillaging and robbery" which he had witnessed,

Stanly resigned early the following year."

(The Old North State and the New, page 243)

Catherine Edmondston's Reaction to the Appointed Governor:

June 12, 1862:

"Stanly, the renegade, the traitor governor, appointed by Mr. Lincoln to rule his native State, finds

the way of the transgressor hard. He has stopped the Negro schools as being contrary to the

Statute Law of North Carolina, by which he has offended his Northern masters, but with a strange

inconsistency he ignores the fact (of which Mr. (George Edmund) Badger has reminded him however)

that his being here, as Gov, is as much an infringement on our rights, for the Laws of N.C. provide

for an election of the Gov by the people.

He said that if there was one man in N.C. whom he regarded more than another,

one man whom he loved, that man was Richard S. Donnell, & yet the first sight which greeted him on

stepping ashore at New Berne was the coffin of Mr. Donnell's mother with her name & the date of her

birth & death cut on it, waiting shipment to NY, her remains having been thrown out to give place

to the body of a Yankee officer! Such is our foe."

June 22, 1862:

"We hear that Lincoln has recalled Stanly from the governorship of North Carolina. How true it is that it

is hard to serve two masters! The shallow artifice by which he attempted to throw dust in our eyes by

professing to govern us by the Statute Laws of N.C. displeased his Northern masters, whilst his

being here at all is such an infringement of our rights that no plausibility could even gild the pill.

Richard Dobbs Speight, Gov of NC, was killed in a duel by Edward Stanly's father many years ago.

His grave was violated by the Yankees when they had possession of New Berne, and his skull stuck

upon a pole was one of the first objects which met Stanly's eyes as he landed in New Berne

as Lincoln's governor, appointed to subjugate his native State."

(Journal of A Secesh Lady, pp. 193-200)

Lincoln's Proconsul Condemns Pillage:

“In a letter to Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, [Edward Stanly] describes the vandalism

of the [Northern] army on its various expeditions:

Had the war in North Carolina been conducted by soldiers

who were Christians and gentlemen, the State would long ago have rebelled against the rebellion. But,

instead of that, what was done? Thousands and thousands of dollars worth of property were conveyed North.

Libraries, pianos, carpets, mirrors, family portraits, everything in short that could be removed was stolen

by men abusing flagitious slaveholders and preaching liberty, justice and civilization. I was informed that

one regiment of abolitionists had conveyed North more that 40,000 dollars worth of property. They literally

robbed the cradle and the grave. Cases were numerous where old men were thrown into prison after the

horses and barns were destroyed by fire they were robbed. I remember one instance where several houses

were burned and robbed, and among others that of a Methodist preacher, whose

Bible, library and only horse were stolen.”

(Bethel to Sharpsburg, pp 237-238)

Appeal to Southern Patriotism at Wilmington:

“During a dress parade [at Camp Davis, near Wilmington] on the evening of May, 31 [1862],

[Col. Collett Leventhorpe] read the infamous “Woman’s Order” (General Orders No. 28), issued by the

Union commander of occupied New Orleans, Maj. Gen. Benjamin “Beast” Butler, in response to various indignities –

spitting, curses, hateful glances, etc. – heaped upon the Yankee soldiers there. Leventhorpe told his troops

[of the 11th, 43rd and 51st North Carolina Regiments]:

“Fellow soldiers: The infamous order which you have just heard, proceeds from the General, whom fortune

of war has placed in possession of one of the noblest cities of the South. The base enemy we oppose, not

content with crimes of invasion, with insurrectionary attempts among our domestic population, and with pillaging

the fairest regions of our country, has now openly dared the threaten our most sacred relations, and to place

our wives and daughters upon the footing of common prostitutes of the town.

Gentlemen of North Carolina, the debased passions of soldiery need no such incentive. The records of crime

written in the sad annals of Maryland, and in those other unfortunate portions of our country which have been

polluted by the enemy’s feet, prove but too well the fate, worse than death, which awaits those most dear

to us in the event of his conquest and our humiliation.

But, fellow soldiers, with the blessing of god, we need fear no such destiny for our country.

Relying then on that blessing, let us resolve as one man that Wilmington shall not be reached by the invader,

and, in the hour or trial, recalling these scandalous threats against our wives and daughters of New Orleans,

let us meet him sternly and hurl him back upon his beats at the point of a bayonet.”

(Collett Leventhorpe, the English Confederate, pp. 70-71)

Plymouth:

Chancellorsville:

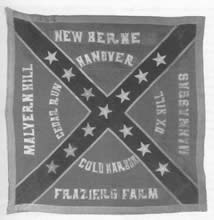

The Gettysburg Campaign -- The First Day

Colorbearers of the 13th North Carolina

By 4PM the Federal forces had retreated to Seminary Ridge, where they formed a hastily constructed line

with breastworks of rails and dirt on the slope fronting the west of the Ridge. The Confederate Brigades of

Brig. Gen. James Lane, Brig. Gen A.M. Scales, and Colonel Abner Perrin, in Maj. Gen Dorsey Pender’s

division of Hill’s corps, charged across an open field and then up the slope, encountering a storm of shot

and shell from the batteries and the musketry of the infantry.

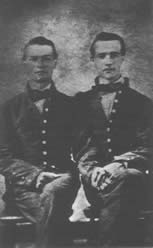

Levi & Henry Walker,

13th North Carolina Regiment

In many cases the colors of the regiments were advanced several paces in front of the line.

Despite taking severe casualties, they pressed on as ordered, without firing “until the line of [Northern]

breastworks in front became a sheet of fire and smoke, sending its leaden missiles of death in the faces

of men who had often, but never so terribly, met it before.”

One of the most incredible events of the battle occurred here, according to John B. Gordon, who fought

with the army throughout is entire existence. Pvt. William Faucette, colorbearer of the 13th North Carolina,

had the colors in his right hand when he received a mortal blow that almost severed his arm, tearing

it from its socket. Without halting or hesitating,

“He seized the falling flag with his left hand, and, with his blood spouting from the severed arteries

and his right arm dangling in shreds at his side, he still rushed to the front,

shouting to his comrades, “forward, forward!”

A few minutes later Pvt. Levi Walker, the fifth colorbearer of the 13th to be hit during this charge, was

shot in the left leg and knocked down. In the 12th South Carolina one colorbearer after another was

shot dead until all four were down. Every one of the colorbearers that went into battle with Perrin’s

brigade was killed, and several regiments had several men pick up the flag and then be wounded or killed.

The charge broke the Federal lines, and panic ensured. Federal troops fled off the entire line…and

headed back to Gettysburg and the safety of Federal reinforcements on Cemetery Hill south of town.

Perrin’s brigade followed the Federals into Gettysburg, with the 1st and 14th South Carolina in the lead.

The Federals ran through the town of Gettysburg in a mad dash to escape capture. Chaos reigned in the

streets, and men who had sought shelter and aid in the residences of citizens found themselves

in danger of being taken prisoner.”

(The Damned Red Flags of the Rebellion, pp. 106-108)

The Twenty-Sixth North Carolina and Col. Henry King Burgwyn

“All the men were up at once and ready, every officer at his post, Col. [Henry] Burgwyn in the centre,

Lieut. Col. [John R.] Lane on the right, Major [John T.] Jones on the left. At the command “Forward March!,”

all to a man stepped off, apparently as willing and as proudly as if they were on review. The enemy at once

opened fire, killing and wounding some…The enemy’s artillery on our right got an enfilade fire. Our loss was frightful.

But our men crossed [Willoughby’s Run] in good order and immediately were in proper position again, and

up the hill we went firing now with better execution.” (John R. Lane, Address at Gettysburg, 1905)

“Their advance was not checked, and they came on in rapid strides, yelling like demons. The Confederates

overpowered the Nineteenth Indiana, striking on both flanks. [The enemy] left was then exposed to an

enfilading fire and was forced to fall back. [Near the western crest of McPherson’s Ridge], the

Twenty-fourth Michigan fought desperately but the Twenty-sixth North Carolina would not be denied.

As Lane later recalled, “the engagement was becoming desperate, It seemed as if the bullets were

as thick as hailstones in a storm. At this time the colors have been cut down ten times, the color guard

all killed or wounded. We have now struck the second line of the enemy where the fighting is fiercest

and the killing is deadliest. Suddenly, Captain W.W. McCreery, Assistant Inspector General of the Brigade,

rushes forward to Col. Burgwyn. He bears him a message. “Tell him,” says General [James Johnston]

Pettigrew, “his regiment has covered itself with glory today.” Delivering these encouraging words,

Capt. McCreery…seizes the fallen flag, waves it aloft and advancing to the front, is shot through the

heart and falls, bathing the flag in his life’s blood.

Lieut. George Wilcox of Company H, now rushes forward, and pulling the flag from under the dead

hero, advances with it. In a few steps he also falls with two wounds – not fatal – in his body.

The line hesitates; the crisis is reached; the colors must advance. The gallant Burgwyn leaps forward, takes

them up and again the line moves forward. Returning again from the right Lieut. Col. Lane sees Col. Burgwyn

advancing with the colors. At this juncture, a brave private, Franklin Huneycutt, of Company B, takes the

colors and Burgwyn turns to hear from the right. Col. Lane says: “We are in line on the right.” Col. Burgwyn

delivers Pettigrew’s message….At that instant he falls with a bullet through both lungs, and at the same

moment brave Honeycutt falls dead only a few steps in advance.

The night of Wednesday, 1 July 1863, would never be forgotten by those who survived the slaughter in

McPherson’s woods. The air was rent by the piteous cries of the wounded, many still lying in the fields

and woods, pleading for water, for succor of any kind, and even perhaps for the ultimate relief that only

death could afford. And none had suffered more than the men of the Twenty-sixth North Carolina.

Out of the approximately eight hundred who had been engaged in that bitter fight…hardly more than two hundred

were able to make their way back to the narrow woods on Herr Ridge.

Although victorious, the Twenty-sixth was virtually destroyed.”

(The Boy Colonel of the Confederacy, pp. 327-336)

The Gettysburg Campaign -- The Third Day:

“Gettysburg was a national field of glory; but the paladins of the battle of July 3 were the native

North Carolinians, [General James Johnston] Pettigrew (born Tyrell County, July 4, 1828) and

Lewis Addison Armistead (born New Bern, February 18, 1817). Pettigrew, leading the spearhead of

the magnificent but forlorn attack, with reckless courage galloped along the advancing lines, giving great

shouts of encouragement to cheer on his men, through whose ranks huge gaps were being

torn by the enemy’s shells.

James Johnston Pettigrew

"Now Colonel, for the Honor of the Good Old North State, Forward."

After his horse was shot under him, Pettigrew led his men forward on foot until he himself was wounded.

Some scores of Pettigrew’s North Carolinians and Archer’s Alabamians and Tennesseans leaped the

stone wall east and south of the “bloody angle,” planted their standards there and drove back the first

Federal line from the wall; but these Confederates were quickly shot down, captured or driven back. In a

desperate gamble for victory, Armistead, leading a few scores of Virginians who followed his plumed hat held

aloft on the point of his sword, had penetrated to a point thirty-three yards east of the wall where he fell

mortally wounded; and most of his men were killed, wounded or captured.

North Carolinians of the division led by Pettigrew advanced to within twenty feet of the stone wall on their front,

about forty yards east of the point where Armistead fell. The easternmost point reached by Pettigrew’s

North Carolinians registered the “high water mark” of the Confederacy on this battlefield.

Pickett’s Virginians, first on the field to encounter the enemy, were the first to give way. Early in the action

[General] Garnett was killed and [General] Kemper grievously wounded. Col. E.P. Alexander, who

commanded the Confederate artillery, categorically states that “Pickett’s force was spent and his

division disintegrated before Pettigrew’s got under close fire.”

When [Northern] artillery opened on Pettigrew’s division, the fire was so devastating that, as [General] Trimble

observed, Pettigrew’s division “seemed to sink into the earth under the tempest of fire.” Responding lustily

to the stirring command, “Three cheers for the Old North State,” Pettigrew’s North Carolinians halted,

coolly returned the enemy’s fire, and then, giving a wild yell, dashed forward once again into the flame.

The North Carolinians sullenly withdrew from the field only after Pickett’s division was almost destroyed…

The desperate onslaught of the North Carolinians in this battle is fully attested by their opponents, who

by their own admission were on the verge of retreat; and the Confederate records attest the feats of valor

under devastating fire of the five North Carolina regiments in Pettigrew’s division which lost nearly as

many men in killed and wounded as the fifteen regiments in Pickett’s division.

William Dorsey Pender

The highest ranking officer from North Carolina to fall at Gettysburg was William Dorsey Pender, to whom

Stonewall Jackson, after receiving his mortal wound at Chancellorsville, called out: “You must hold your

ground General Pender, you must hold your ground, sir.” Three weeks later he was promoted to major-general,

and the first battle he wore the stars of that rank was Gettysburg. On the second day he was mortally wounded

and died on July 18. General Pettigrew, a grandson of Charles Pettigrew, the first “bishop-elect” of the

Episcopal church in North Carolina, survived the final assault at Gettysburg, but on July 14 when his division

reached the Potomac he was wounded in a surprise attack by Federal cavalrymen and died three days later.

[On] July 20 the Carolina Watchman said editorially of Gettysburg: “We do not see from all accounts received

how the Yanks can claim it a victory, when, if they had been successful, they could have permitted the

defeated army to withdraw and march to Hagerstown without pursuing it.”

(North Carolina, The Old North State and the New, pp. 257-259)

"[Pettigrew] was the highest ranking officer still on his feet in the brigade, and he had been wounded twice.

Every other colonel, lieutenant colonel, and major in the North Carolina brigade was dead or badly wounded

except for one who had been captured a few yards from the stone wall. The Twenty-sixth North Carolina had

gone into the first day of Gettysburg with more than 800 men and cam out with 216. After the third day's

action there were eighty men present for duty, a good-sized company.

On 7 July...Pettigrew dashed off a note to Governor [Zebulon] Vance, in as tone as exultant as a victor,

telling him that his old regiment, the Twenty-sixth, had covered itself with glory.

"None had more deeply at heart than he the cause for which he shed his blood," wrote Colonel [Collett] Leventhorpe.

"He gave himself up to it wholly, with all his fine energies, extraordinary talents, and the courage of a heart literally

ignorant of fear...I tell you the truth when I say that I have never met with one who fitted more entirely my "beau ideal"

of the patriot, the soldier, the man of genius, and the accomplished gentleman."

(Carolina Cavalier, pp. 200-205)

The Aftermath of Gettysburg:

Twenty-year old Captain Oliver Evans Mercer of Company G, 20th North Carolina Regiment was killed on the

first day of fighting at Gettysburg. Mercer joined the “Brunswick Guards” at Camp Howard in Brunswick county

in June 1861. Not knowing of her son’s fate in the battle, Mercer’s mother wrote Virginia-born Dr. J.W.C. O’Neal

who was identifying, recording and burying the Confederate dead left on the battlefield:

“Our Wilmington papers bring the welcome intelligence to many bereaved Southern hearts that you have

cared for the graves of many of our confederate dead at Gettysburg, replaced headboards and prepared a

list of names. May the Lord bless you is the prayer of many Southern hearts. Oh! We have lost so much.

There are but few families that do not mourn the loss of one or more loved ones, and only a mother who

has lost a son in that awful battle can and does appreciate fully such goodness as you have shown.

I, too, have lost a son at Gettysburg, a brave, noble boy in the full bloom of youth, and my heart yearns to

have his remains, if they can be found, brought home to rest in the soil of the land he loved so well. I need

your assistance and I am confident you will aid me. No sorrow-stricken mother could ask and

be refused by a heart such as yours.”

(Debris of Battle, Gerard A. Patterson)

Northern Raid in North Carolina – July 19-23, 1863

"A band of the Union troops almost seized former North Carolina governor Henry T. Clark at his plantation

home just outside of Tarboro. On the morning of the raid Clark was preparing to start his daily

horseback ride when he spotted the approaching Yankee cavalrymen. The soldiers sighted the former

governor, and what would have been just a peaceful ride on a summer morning became a desperate

dash into the woods. Unable to catch Clark, the Union troops returned to loot his house. The State Journal

reported that "Ex-Gov. Clark's residence, on the suburbs of the town, was shamefully abused. Mrs. Clark

and her niece, Miss Bettie Toole, were compelled to leave their house and take refuge in the kitchen.

They ransacked the house from top to bottom, breaking open trunks, chests, and drawers." Much of their

food was stolen, thrown down the well, or otherwise ruined, and the raiders plundered Clark's "stock

of wines and brandies.”

The Federal soldiers also raided the Branch Bank of Tarboro; fortunately, the valuables entrusted to the bank

had been taken away and hidden. The bank cashier was robbed of his watch and clothing while the raiders

searched the bank. The luckless cashier's home was also plundered that day. From Tarboro's Masonic lodge

the raiders "carried off the fine regalia of the Chapter and all the jewels and emblems even to the common

gavel, and damaged what could not be removed.”

(The Yankees Have Been Here, NC Historical Review, David A. Norris, January, 1996, pp. 12-13)

The Wilderness Campaign:

Spotsylvania: "A Butchery Pure and Simple"

“Elsewhere along the front, Grant had ordered attacks by all four Union corps against various points

of the Confederate fortifications. Most of these assaults failed to produce any positive results,

except a…charge that penetrated [General Richard] Ewell’s breastworks. The stalemate around

Spotsylvania continued. That evening [May 10, General Harry] Heth marched his division back to

reoccupy the ground on the far right in front of the Spotsylvania Court House. The 11th and 44th

North Carolina took up positions near an eastern bulge in the defensive line known as “Heth’s Salient.”

That night Lee, A.P. Hill, and several other generals congregated at Heth’s headquarters

in the Massaponax Church. A discussion arose among the generals about Grant’s tactics.

Unlike any other Union general they had fought, Grant had launched sudden assaults against

them on May 5, 6, 8 and 10. These attacks failed to overpower the Confederates and

cost thousands of Union lives. Grant’s aggressiveness not only amazed

the senior officers, it also appalled them.

The Confederate generals severely criticized Grant’s bludgeoning tactics. To their astonishment,

General Lee voiced a different opinion. More than any other Confederate general, Lee understood

that Grant’s pugnacity had smothered their ability to strike a powerful counterblow. Heth, Hill,

and the others saw the body count and thought they were winning.

Lee saw an opponent who kept attacking and worried.

[Lee] predicted Grant would withdraw in preparation for another move toward Richmond or Fredericksburg.

He then expressed a desire to attack Grant’s forces as they moved. Lee turned to Heth and

said, “I wish you to have everything in readiness to pull out at a moment’s notice, but

do not disturb your artillery, unless you commence movement. We must attack these

people if they retreat.” Lee rebutted their arguments with a remarkable insight:

“This army cannot stand a siege; we must end this business on the battlefield, not in a fortified place.”

Before dawn [on May12], Grant launched yet another massive assault against the Confederate

defenses. By 5 [AM] o’clock the engagement had become very hot. Burnside’s attack pressed

against pockets of the 11the North Carolina [and] Lt. Col. Frank Bird [of Bertie county] described

the savage fighting as “the hardest fought battle probably of the war.” The enemy made repeated

charges on our works but was repulsed with most terrible slaughter…I am unhurt, how I am unable

to say. I have been in the hottest battles.”

Despite the intense combat and persistent Union assaults, the regiment suffered only light casualties.

Frank Bird explained the disproportionate loss rate to his sister: “The accounts which you see in the

papers of our having killed and wounded so many more of them [Union troops] than they of is, are

not I think exaggerated. The difference is truly wonderful and I only account for it in one way. They

advanced on us in so many lines of battle, and were therefore so thick that we could not miss them.”

Although the regiment suffered little, personal tragedy struck Lewis Warlick [of Burke county]. Pvt. Logan

Warlick, his brother, was one of the few men killed on May 12. Warlick wrote home to his sister-in-law

to break the sad news to the family. A second Warlick son had died while serving in the Bethel Regiment.”

“Grant is twice as badly whipped as was Burnside and Hooker but he is so determined

he will not acknowledge it,” wrote Warlick.”

[The 11th North Carolina, or “Bethel Regiment,” was comprised of men from Mecklenburg, Burke, Bertie,

Chowan, Orange Lincoln and Buncombe counties.]

(More Terrible Than Victory, pp. 166-170)

Southern women during the war were known to have destroyed their precious libraries than to

allow Northern occupiers to enjoy its contents, as well as knocking in the heads of wine casks rather than

permitting Northern soldiers to sample their choice contents. The author of the following was

born in Indiana, migrated to Virginia in 1857 and later served in the Nelson (Virginia) Light Artillery.

The Temper of the Women:

“During the latter part of the year in which the war between the States came to an end,

a Southern comic writer, in a letter addressed to Artemus Ward, summed up the political

outlook in one sentence, reading somewhat as follows: “You may reconstruct the men, with your

laws and things, but how are you going to reconstruct the women? Whoop-ee!”

Now this unauthorized but certainly very expressive interjection had a good deal of truth at its back,

and I am very sure that I have never yet known a thoroughly “reconstructed” woman.

The reason, of course, is not far to seek.

The women of the South could hardly have been more desperately in earnest than their husbands

and brothers and sons were, in the prosecution of the war, but with their women-natures they gave

themselves wholly to the cause.…to doubt its righteousness, or to falter in their loyalty to it while

it lived, would have been treason and infidelity; to do the like now that it is dead would be

to them little less than sacrilege.

I wish I could adequately tell my reader of the part those women played in the war. If I could

make these pages show half of their nobleness; if I could describe the sufferings they endured, and tell

of their cheerfulness under it all; if the reader might guess the utter unselfishness with which they

laid themselves and the things they held nearest their hearts upon the altar of the only country

they knew as their own, the rare heroism with which they played their sorrowful part in

a drama which was to them a long tragedy;

[I]f my pages could be made to show the half of these things, all womankind, I am sure, would tenderly

cherish the record, and nobody would wonder again at the tenacity with which the women of the

South still hold their allegiance to the lost cause.

Theirs was a particularly hard lot. The real sorrows of war, like those of drunkenness, always fall

more heavily upon women. They may not bear arms. They may not even share the triumphs which

compensate their brethren for toil and suffering and danger. They must sit still and endure. The poverty

which war brings to them wears no cheerful face, but sits down with them to empty tables

and pinches them sorely in solitude.

After the victory….[the] wives and daughters await in sorest agony of suspense the news which may

bring hopeless desolation to their hearts. To them the victory may mean the loss of those for whom they

lived and in whom they hoped, while to those who have fought the battle it brings only gladness.

And all this was true of Southern women almost without exception.

[The] more heavily the war bore upon themselves, the more persistently did they demand that it should

be fought out to the end. When they lost a husband, a son, or a brother, they held the loss only an

additional reason for faithful adherence to the cause. Having made such a sacrifice to that which was

almost a religion to them, they had, if possible, less thought than ever of proving unfaithful to it.”

(A Rebel’s Recollections, George Cary Eggleston, Indiana University Press, 1959, pp. 83-85)

Cold Harbor:

"[Governor Zebulon] Vance received a letter from Petersburg, Virginia, dated July 20, 1864, which showed how

heavily the anguish of war bore on both sides. Captain john S. Dancy of the 17th North Carolina wrote of Grant's

ill-conceived assault on the Confederate lines:

"I forward you a Yankee flag captured at Cold Harbor, Virginia, on the 3rd of June 1864 by the 17th N.C. Regt.,

Col. W.F. Martin. It belonged to the 164th N.Y. Volunteers, who charged boldly up to within seventy-five yards of

the lone of the 17th Regiment and were literally cut to pieces. A few prisoners captured by us stated that themselves

and three others who reached their lines safely were the only ones left of the Regt. All the field and company officers

were killed in the immediate front of the 17th and the Yankee bodies were literally piled upon one another.

I forward the flag to you as the Executive of the State, with the hope that it may be taken care of or measures

taken to remember it as the capture of the 17th N.C. Regt."

(Zeb Vance, Champion of Personal Freedom, page 387)

The Petersburg Campaign:

Living Skeletons Defending Petersburg

“After the Union disaster at “the Crater,” the armies returned to three weeks of uneventful trench warfare.

During the first twenty days of August [1864], “nothing occurred with us to break the monotony

in the trenches, such as it was,” according to [General Johnson] Hagood. [General Alfred H.]

Colquitt’s brigade was permanently returned to Hoke on August 2.

On August 19, [Colquitt’s, Hagood’s and General Thomas L. Clingman’s brigades were assigned

to General William Mahone] in Lee’s unsuccessful three-day effort to dislodge the Federals from

the Weldon and Petersburg Railroad. Of the 681 officers and men Hagood sent into the battle,

only 292 emerged unscathed. General Clingman was seriously wounded in the

leg on the first day of the engagement and was lost to Hoke for the remainder of the war.

Because of deadly attrition and the casualties sustained on August 21, Hagood asked that

he be allowed to take his survivors “to some quiet camp where rest and access to water

might recruit their physical condition.” His request was granted by Lee.

When the 740 frail soldiers of his command emerged from the Petersburg trenches on August 20,

they represented just a third of the complement that had entered the works sixty-seven days earlier.

The brigade inspector was delighted when a local citizen offered his forty-acre estate in

nearby Chesterfield County for a camp site.

In mid-September, Hoke was granted permission to pull his other weary brigades from the

trenches and take them to the utopia being enjoyed by Hagood’s men. Of the twenty-two

hundred soldiers on hand when Brigadier-General [James G.] Martin put his soldiers in

the trenches, seven hundred “living skeletons” scrambled out under the command of

General [William W.] Kirkland on Thursday, September 15.

For ten days, Hoke and the worn and jaded men of his division enjoyed overdue pleasures.

In a letter to his sister, Lieutenant Edward J. Williams of the Thirty-first North Carolina

expressed the excitement that abounded: “The most pleasant topic amongst us . . .

is that we are at last clear of the ditches, shells, & [bales] of every description & are lying

at ease on a beautiful hillside washing our faces at least once per day and no work to do.

Since the 15 of June we have held a portion of the works in front of

Petersburg & have never been relieved until now.”

The brief respite from war ended all too soon on September 28, when the men returned to the trenches.

As a climax to the period of rest and relaxation, the division was honored with a grand review by General Lee

. . . dressed in full uniform with a yellow sash, was atop Traveller as he rode past the

remnants of Hoke’s four brigades.”

(General Robert F. Hoke, Lee’s Modest Warrior, Daniel W. Broadfoot, John F. Blair, 1996, pp. 218-219)

A Glorious Victory---North Carolinians at the Battle of Ream’s Station:

"On August 25, 1864, the three brigades of North Carolinians under Generals James H. Lane,

John R. Cooke and Wilmingtonian William MacRae were concentrated in a wooded area opposite the right

flank of Northern forces. MacRae had told his men that he knew they would go over the enemy works, and

that he wished them to do this without firing a gun.

Gen. William MacRae

The artillery fire of Col. William J. Pegram swept the enemy forces before the brigades advanced

late in the afternoon, charging up to the Northern earthworks and fighting hand to hand---ending

with a full rout of the enemy. MacRae had instructed Lt. W.E. Kyle and his sharpshooters to concentrate

upon the Northern artillery batteries firing at his forces, thus eliminating this threat. Once captured, the

guns were turned upon the fleeing enemy by Captain W.P. Oldham of Wilmington and his men of

Company K of the 44th North Carolina who opened a devastating fire.

“In a moment of panic our troops gave way,” a Northern colonel wrote (and) soldiers either threw themselves

on the ground in surrender or fled across the railroad. Never in the history of the Second Corps

had such an exhibition of incapacity and cowardice been given, a Northern soldier asserted. Author James

Robertson’s states in his “A.P. Hill, Story of a Confederate Warrior” that “of the 2700 (Northern) casualties,

2150 had surrendered on the field…in addition, the [Northern] army had lost 9 cannon, 3100 small arms and

32 horses. The [Northern commanding general] was so humiliated by the rout at Ream’s Station that

he submitted his resignation from the army.”

Col. Pegram’s artillery battalion thought very highly of MacRae’s brigade and felt that their guns could never

be captured by the enemy with MacRae supporting them. General Robert E. Lee publicly and repeatedly

stated that not only North Carolina, but the whole Confederacy, owed a debt of gratitude to Lane’s, Cooke’s

and MacRae’s brigades which could never be repaid---and personally wrote to Governor Zebulon Vance expressing

his high appreciation of their services. In his letter to Vance, Lee stated “If the men who remain in North Carolina

share the spirit of those they have sent to the field, as I doubt not they do, her defense may securely be

trusted to their hands.”

It is said that the great success of the assault at Ream’s Station was largely the result of the keenness of

MacRae in selecting the right moment to strike at the enemy without awaiting orders to do so. At his next major

engagement with the enemy at Burgess’ Mill in October 1864, MacRae’s brigade once again displayed coolness

and gallantry in battle. After an assault that broke the enemy line and captured an artillery battery, his brigade was

left unsupported while an enemy counter-attack closed upon his flanks. A desperate struggle to hold his position

ensued until nightfall, when his brigade fought through the new enemy lines that were forming to their rear.

The brigade entered that battle with 1,050 troops, with all but 525 being casualties of the engagement.

Though many times in exposed and dangerous positions himself, General MacRae suffered only one wound to the

jaw, and his uniform was pierced often by bullets and shrapnel. His sabres suffered the most damage with

two being cut in half by shots. Though he lacked formal military training, MacRae was described as

“one of the finest brigade commanders in Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia” and a brilliant tactician knowing

when best to strike an enemy, and where.

General MacRae and his brigade were not involved in the second Battle of Hatcher’s Run of February 1865 in

which some Southern units suffered severe losses. General A.P. Hill recognized MacRae’s value to his army

and later testified that “had William MacRae been here, the result would have been different.”

(Wilmington's Fighting Brigadier, www.cfhi.net)

Pocket Bible Saved His Life:

“With a loud cry, the Confederates advanced, forcing the Federal pickets to flee toward their main lines.

A few moments later after Lane and Cooke had made contact with the Federals, another Confederate brigade,

under General [William] MacRae, crashed into the Federal works and gained a foothold inside.

The Thirty-seventh [North Carolina], positioned near the center of Lane’s brigade, made the next

breakthrough. Hysteria-stricken Federal soldiers streamed to the rear. The Federal officers attempted

to get their men to counterattack, but their efforts were in vain, as the Union soldiers started

surrendering or heading for the rear.

But the fire concentrating on the Thirty-seventh was intense. “in gaining this point,” Major Bost would write,

“the Regt was exposed to a heavy fire of grape shot and bullets.” Portions of Lane’s brigade started falling

back, while other portions, including most of the Thirty-seventh, intermixed with elements of Cooke’s brigade,

pressed ahead, “capturing prisoners, caissons, horses…” Much of the fighting was done hand to hand.

Private Thomas M. Hanna (Company H) was one of the soldiers slightly wounded during the battle.

He would pen this account of his ordeal to his wife a few days after the battle:

“Dear wife:…God has spared my life through another bloody battle…The day I commence it we

were marched all night and fought the Yankees at Ream Station….we had to march 20 miles to get around

them in the hottest weather I ever felt. We had a desperate fight, made the attack and drove them from

their breast works…We also lost pretty heavily…I myself slightly wounded in the right breast. The ball struck

my pocket bible, and went halfway through it. [It] kill[ed] a man dead just in front of me and the doctor said it

would have killed me if it had not struck my pocket Bible.

A Gaston County pastor would relate many years after the war that the bullet had made “a track through

[the Bible] from Genesis to John…” and that the minie’ had come to rest on the “14th chapter of John…

”Peace be with you, my peace I give unto you.” Hanna would continue in his letter to his wife after the battle:

“I don’t know what I will do for a Bible, mine is ruined, torn and bursted all to pieces.”

(The Thirty-Seventh North Carolina Troops, Michael C. Hardy, pp. 207-209)

General Stephen Dodson Ramseur’s Furlough:

To oppose Sheridan’s army of about fifty thousand men [in the Shenandoah Valley in Autumn 1864],

[General Jubal] Early had four small divisions of infantry, a little cavalry and artillery, less than twenty thousand

in all. [General] John B. Gordon, commanding one of Early’s brigades…saw Sheridan’s camps spread out

below him in the Valley, and saw that the left flank was weak and could be turned. He was given three divisions,

his own and those of [General Stephen D.] Ramseur and [General John] Pegram, with which to cross the

mountain and attack the Union flank and rear….The attack was to be made just

at daybreak of October nineteenth.

Through the night before, quietly and secretly, the flanking column filed over the steep mountain.

Gordon and Stephen Ramseur, young North Carolina Major-General, sat on a bluff overlooking the

movement, through the night.

Ramseur had married since the war began; to him had been born a daughter, whom se had never seen.

He talked that night of the daughter, and of the young mother, and of his deep longing for a pause

that he might go home. As dawn he rose and started to his place in the battle line. “Well, Gordon,” he

remarked quietly and with perfect assurance, “I shall get my furlough to-day.”