North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

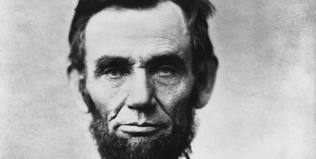

Lincoln and the First Shot of War

Prelude at Charleston Harbor

The small garrison of Major Robert Anderson at Fort Moultrie was under no military threat after the

secession of South Carolina, though that State saw no reason for United States troops to be on

their soil. If Anderson viewed his position at Moultrie as “exposed,” it was due to his government not properly

recalling him from a now-foreign country which was at peace with the United States, and sending

commissioners to Washington to negotiate peacefully.

Secession in no way prompted war, as the disagreements between North and South could have been

settled without armed conflict. President James Buchanan disagreed with secession but rightly

observed that as president, he had no constitutional authority to stop a State from withdrawing,

or could force a State to return. Buchanan was also an highly-experienced diplomat and saw statecraft,

arbitration and negotiation as the proper solution to America’s problems.

Lincoln was an old- line Daniel Webster/Henry Clay Whig and recent covert to the Republicans; as an

old-line Whig he believed in a consolidated central government with full authority over individual States,

high protective tariffs, a national bank, and government subsidy of internal improvements and private industry.

His actions before and after the Sumter crisis followed a predictable course.

Through the historical record, letters and diary entries between Lincoln and his cabinet and advisors,

and the reports of the Confederate commissioners in Washington, it is clear that Lincoln manipulated the South

into firing the first shots of the war. By doing this, he roused the lethargic and mostly disinterested North

into supporting his war against the American South.

Aggressions Against South Carolina:

“From the Confederate point of view the United States had made itself the aggressor long before Lincoln

acted to strengthen any fort. It was aggression when, on December 26, 1860, Major Anderson moved

his small force from their exposed position at Fort Moultrie to the somewhat more secure one at

Fort Sumter. Indeed, it was a continuing act of aggression every day that United States forces

remained in Sumter or any other place within the boundaries of the Confederacy.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pg. 207)

“Nationalistic appeals had been pouring into Washington from all over the North since January [1861],

filling the pigeonholes of the government’s foremost Unionists. Bellicose editorials had echoed those

demands, insisting on federal coercion against any State that attempted to secede.

Lincoln continued to receive many such letters, including one that promised him political oblivion

for his evident weakness. “Give up Sumpter,” wrote an anonymous correspondent, “& you are as

dead politically as John Brown is dead physically.” A Cincinnati man advised him that anything could

be borne but peaceful separation; supply Sumter at any cost . . . although he finally admitted

that it would be better still if the Confederates attacked it and slaughtered the garrison.

The ferocity of such comment, if not its volume, reassured many Republicans in Washington that

their political survival required a stubborn stance against compromise, which would in turn fuel

charges that party interest ultimately trumped national interest.”

Historians have since cited political necessity as at least partial explanation for the attitude

that led Lincoln to adopt a course that might best be described as passive aggression.”

(Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, pg. 18)

“In pondering his options regarding the Charleston crisis, Lincoln proved highly receptive to a plan

presented by his postmaster general, Montgomery Blair. The plan’s author, however, was Blair’s

brother-in-law, Gustavus V. Fox. Blair took him to the Executive Mansion on March 13, the same

day on which Lincoln had refused to meet with the Confederate commissioners. The resident was

enthusiastic about the possibility of a Fort Sumter expedition that would serve his ends.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 87)

“[Secretary of State] William H. Seward, who favored a peaceful solution of the sectional crisis,

argued that aid to Florida’s Fort Pickens would be less likely to lead to war than aid to Fort Sumter.

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 91)

“It cannot be denied,” conceded the New York Times on March 21, with vernal candor, “that there

is a growing sentiment throughout the North in favor of letting the Gulf States go.” That same

day the Philadelphia Inquirer called for popular elections in the seceded States to determine the

true measure of public sentiment, with peaceful division to follow a positive outcome, while the

Daily Intelligencer in Washington City endorsed a national convention of the remaining States

to bless the de facto division.

The following day Washington’s States and Union [illustrated] the wisdom of allowing the dissatisfied

States to take their portion of the nation’s wealth and depart, rather than holding them by force

in a union founded on mutual devotion.

On March 23 the Cincinnati Daily Commercial, which had backed Lincoln, acknowledged

growing popular acceptance of the confederate government and urged letting the South

have its experiment in independence. Delaware’s independent Smyrna Times, which had stood

firmly for the Union for four months, finally agreed that the South should go in peace

if it could not be held by persuasion.”

(Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, pg. 19)

“Throughout the South the President’s inaugural address had antagonized secessionists and

disheartened their opponents. The . . . Richmond Enquirer called it a war declaration:

“Sectional war, declared by Mr. Lincoln, awaits only the signal gun form the insulted Confederacy,

to light its horrid fires all along the border of Virginia. No action of our Convention can now maintain

the peace. She must fight! The liberty of choice is yet hers. She may march to the contest with

her sister States of the South, or she must march to the conflict against them . . . “

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pp. 52-53)

“[Lincoln] told [Illinois Senator Orville] Browning (as Browning recorded in his diary):

”He himself conceived the idea, and proposed sending supplies, without attempting to reinforce,

giving notice of the fact to Gov. [Pickens] of SC. The plan succeeded. They attacked Sumter –

it fell, and thus did more service than it otherwise could.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pg. 181)

“To most Northerners of the Civil War generation, it seemed obvious that the Southerners

had started the war. To certain Northerners, however, and to practically all Southerners,

it seemed just as obvious that Lincoln was to blame.

While the war was still going on, one New York Democrat confided to another his suspicion

that Lincoln had brought off an “adroit maneuver” to “precipitate the attack” for its “expected effect

upon the public feeling of the North.” A one-time Kentucky governor, speaking in Liverpool, England,

stated that the Republicans had schemed to “provoke a collision in order that they might say

that the Confederates had made the first attack.”

The Richmond journalist E.A. Pollard wrote in his wartime history of the war that Lincoln had

“procured” the assault and thus, by an “ingenious artifice,” had himself commenced the fighting.

“He chose to draw the sword.” The Petersburg Express asserted, “but by a dirty trick

succeeded in throwing upon the South the seeming blame of firing the first gun.”

[After the war, Alexander H.] Stephens . . . patiently explained that the aggressor in a war is

not the first to use force but the first to make force necessary. “He who makes the assault is not

necessarily he who strikes the first blow or fires the first gun,” Jefferson Davis wrote.

Referring to the Republicans and the Sumter expedition, he elaborated: “To have waited for further

strengthening of their position by land and naval forces, with hostile purposes now declared,

would have been as unwise as it would be to hesitate to strike down the arm of the assailant,

who levels a deadly weapon at ones’ breast, until he has actually fired.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pp. 182-183)

“In a book (1882) purporting to give the “true stories” of [Forts] Sumter and Pickens, and

dedicated to the “old friends” of [Major] Robert Anderson, a lieutenant-colonel of the United

States Army maintained that the advice of [General Winfield] Scott and [Secretary of State

William] Seward to withdraw from Sumter was quite sound from a merely military standpoint.

“But Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Blair judged more wisely that it would be better to sacrifice the garrison

of Sumter for political effect.” They sent the expedition “with the knowledge that it would compel

the rebels to strike the first blow. If the last man in the garrison of Sumter had perished, it would

have been a cheap price to pay for the magnificent outburst of patriotism that followed.”

In their ten-volume history (1890) Lincoln’s former private secretaries, John G. Nicolay and John Hay,

wrote that Lincoln cared little whether the Sumpter expedition would succeed in its provisioning attempt.

“When he finally gave the order that the fleet should sail he was master of the situation . . . master if

the rebels hesitated or repented, because they would thereby forfeit their prestige with the South;

master if they persisted, for he would then command a united North. But to make the issue sure,

he determined in addition that the rebellion should be put in the wrong.” His success entitled

him to the high honors of “universal statesmanship.”

In later generations a number of writers repeated the view that Lincoln himself had compelled the

Confederates to fire first. Most of these writers inclined to the opinion that, in doing so, he exhibited

less of universal statesmanship than of low cunning.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pp. 184-185)

“Not till 1935, however, did a professional historian present a forthright statement of the thesis

with all the accoutrements of scholarship. In that year Professor Charles W. Ramsdell, of the

University of Texas . . . summed up the case:

“Lincoln, having decided that there was no other way than war for the salvation of his administration,

his party and the Union, maneuvered the Confederates into firing the first shot in order that they, rather

than he, should take the blame for beginning bloodshed.”

According to the Ramsdell argument, Davis and the rest of the Confederate leaders desired peace.

They were eager to negotiate a settlement and avoid a resort to arms. But Lincoln, not so

peaceably inclined, refused to deal with them.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pg. 185)

“The stratagem was a shrewd one, worthy of the shrewd man that Lincoln was. He decided

to send the expedition and – most cleverly – to give advance notice. A genius with words,

he could make them mean different things to different people. To Northerners . . . the government

was taking groceries to starving men and would not use force unless it had to.

To Southerners the same words carried a threat, indeed a double threat. First, Sumter was

going to be provisioned so that it could hold out. Second, if resistance should be offered,

arms and men as well as food was going to be run in!

The notice was timed as carefully as it was phrased. It was delivered while the ships were

departing from New York. They could not reach their destination for three days at least, and so the

Confederates would have plenty of time to take counteraction before the ships arrived. Supposing

the entire force [including the ships heading for Fort Pickens] was heading for Charleston . . .

they had all the more reason to move quickly.

The ruse worked perfectly. True, the expedition neither provisioned nor reinforced Sumter;

it gave the garrison no help at all. But that was not the object. The object was to provoke a shot

that would rouse the Northern people to fight.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pp. 186-187)

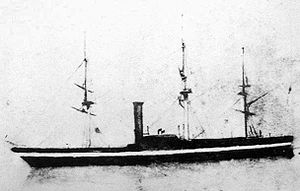

“The element of surprise was lost when the New York Herald published a list of “armaments

and troops, of the fleet [dispatched] from New York and Washington to Charleston Harbor,

for the relief of Fort Sumter.” Newspaper readers learned that three vessels

had sailed under sealed orders on Saturday, April 6.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 92)

“When [Lincoln] replied to the Virginia delegates at the White House, on April 13, he said in

an almost triumphant tone that the “unprovoked assault” would set him “at liberty” to go beyond

the self-imposed limitations of his inaugural and to “repossess” as well as “hold, occupy and

possess” Federal positions in the seceded States.

When he consoled the frustrated [Gustavus V.] Fox, on May 1, he wrote: “You and I both

anticipated that the cause of the country would be advanced by making the attempt to provision

Fort-Sumpter, even if it should fail, and it is no small consolation now to feel

that our anticipation is justified by the result.”

When he drafted his first message to Congress, for the July 4 session [and read it] to

Senator Orville] Browning, on July 3, he went on to remark, as Browning paraphrased him:

“The plan succeeded. They attacked Sumter – it fell, and thus,

did more service than it otherwise could.”

(Lincoln and the First Shot, pp. 192-193)

“Northern newspapers called the garrison “the heroes of Fort Sumter.” Before they reached

their destination, artisans were already working on the Sumter medal commissioned by the

New York Chamber of Commerce for presentation to [Major Robert] Anderson. At a parade on

April 20, thousands thronged the streets to take an excited part in what was described as

“America’s most gigantic tribute.”

Horace Greeley had mixed emotions. “Sumter is lost,” he mourned before rejoicing, “Freedom is saved!”

Nevertheless, in nearly every Northern State, a minority of voices joined in protest or despair.

At Saint Clairsville, Ohio, editors of the Gazette and Citizen hoped that Congress would soon

impeach Lincoln and give him “the reward of a traitor.”

Grimy [South Carolina] gunners boasted, “The sacred soil of South Carolina is free! We have thrown

out the invaders from the North.” Regarded in the South as lawful and legitimate, secession was

considered by many to have been vindicated. With US forces removed from Charleston, said optimists,

the peace movement would gain strength. Perhaps the new president would now consent

to submit the issue to the Supreme Court.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pp. 104-105)

“Had Northern voters been given an opportunity to register their views . . . a substantial

segment would have voiced opposition to any move likely to bring about armed conflict between the

sections of the country. Movements designed to effect “peaceful separation” or to hold a mediated

conference whose goal was compromise got nowhere.

From the time of his surprise inauguration, Lincoln harbored a vision from which he never wavered.

He would quickly restore the Union in its entirety . . . [and] initiate a Second American Revolution

by which he would bring to mature fulfillment the glorious promises of the Declaration of Independence.

Thus his General Order No. 1, issued January 22, 1862, called for the concerted advance of all armies

on or before the symbolic date of February 22, Washington’s birthday.

[The] president made his position clear: “My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union,

and is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 64)

“Several Northern newspapers suggested that Lincoln’s actions were designed to evoke the chain

of events that followed. In Pittsburgh it was said that Jefferson Davis and his subordinates

“ran blindly into the trap” set by the first Republican president,

that “Lincoln used Fort Sumter to draw their fire.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 107)

“Addressing Evangelical Lutherans on May 13, 1862, [Lincoln] spoke of “the sword forced into our hands.”

As late as Lincoln’s brief but carefully crafted second inaugural address, he noted that four years earlier

“all thoughts were anxiously directed to an impending civil war.” In almost self-righteous fashion, he laid

blame for the long and bloody war squarely upon the shoulders of the secessionists at

Charleston to whom he had given two unacceptable choices . . . . . . .”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 109)

“Lincoln expected too much of Unionists in the South, failed to grasp the depth of State pride

in the South and East, and did not dream that secessionists would fight so fiercely for

“homes and firesides.” Although met promptly, his call for men did not signal the quick

capitulation by his foes. Instead it started a fast-moving series of increasingly

severe strikes and counterstrikes.”

(Lincoln’s Little War, pg. 122)

“Sumter surrendered on April 14 [and] Lincoln began composing a proclamation appealing

to the individual States for seventy-five thousand militia for three months of federal service –

the maximum allowed by law. [Montgomery] Blair’s expectation that [Lincoln’s] decisive action

would cultivate latent loyalty even in the border States [was probably the reason] Lincoln’s

proclamation went out to the country the next morning. With it came a call for Congress to

meet in special session, but not until July 4; for the present,

Lincoln intended to make all the decisions himself.

The president sorely misjudged the upper South if he expected his marital gesture to arouse

Unionism there. His proclamation instantly cost him half the remaining slave States and

vastly augmented the Confederacy in both population and territory, not to mention political

sympathy. Even Northern immigrants who lived or worked in the South understood how the

burning resentment of federal aggression inspired a virtual unanimous spirit of resistance.”

(Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, pp. 27-28)

Lincoln, undoubtedly a skilled politician, had a primary goal -- to suppress an independence

movement in the South. That he was able to defeat this independence movement attests to

his impressive political abilities and acumen. He led a very divided Republican party and North down

a trail of dubious constitutional measures and questionable legality, survived enormous military

losses, especially in 1864 when his re-election seemed impossible,

and managed to overwhelm all opponents.

Admitted by his political appointees and subordinates, the full power of the War Department

was enlisted to police the polls and ensure his reelection in 1864 after a vocal Northern peace

movement was gaining momentum. Had that peace movement blossomed and had George

McClellan elected president in 1864, the Northern Democrats would probably have pursued

and armistice and compromise measures in an attempt to settle the sectional differences.

“In his zeal to preserve the Union, [Lincoln] abandoned statecraft, exploiting the delicate issue

of Fort Sumter and committing the nation to a bloodbath far worse than he or any of his advisors

ever envisioned. At the time, his belligerent course promised no better result than maintaining

the territorial integrity of the United States at the expense of weakening the Constitution,

and with no initial hint at eliminating slavery.

In his mission to preserve the nation’s geographic boundaries, Lincoln quickly violated his oath

to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” He did so in the executive

power he assumed, in the increase of federal authority that he imposed in order to prosecute

the war, and in his arbitrary suspensions of constitutional liberties.

By sheer military might his proxies deposed the duly elected legislatures of two States of the Union.

If he did not resurrect the Roman custom of dictatorship in a time of crisis, he did introduce a

modified form of the concept in a republic that would previously never have borne it.

Lincoln gradually arrogated so much authority to his office that his own dominant party dared not pass

that power on to a member of the opposition. When the Democrat Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln

and resisted Radical Republican aims, a Republican Congress and Supreme Court quickly curtailed

presidential powers through legislation, judicial interpretation, and political maneuvers, including the

first exercise (and the first abuse) of the power to impeach a president. Unfortunately, no

retroactive restraint could restore the antebellum intolerance to authoritarian government.

Lincoln . . . might have averted the clash [at Sumter] had he been willing to negotiate a

peaceful separation, but he represented a nationalist faction [and culmination] of a peaceful settlement

would have demanded truly inspired statecraft: instead, Lincoln elected to risk a confrontation at

Fort Sumter even though his personal emissary, Stephen Hurlbut, had assured him

that it would end in violence.

By the end of his first year in the White House he had probably begun to understand the

depth of his misjudgment on that point, although he may not yet have begun to imagine

how ghastly the consequences would be.”

(Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, pp. 281-282)

Sources:

Lincoln’s Little War, Webb Garrison, Rutledge Hill Press, 1997

Lincoln and the First Shot, Richard N. Current, J.B. Lippincott Company, 1963

Mr. Lincoln Goes to War, William Marvel, Houghton Mifflin, 2006,

Copyright 2013, The North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission