North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

Christmas in North Carolina and the South

Christmas in North Carolina in antebellum times was more a religious and family tradition

and celebrated without official ceremony. Except for doubling the watch, the town commissions

ordinarily made no occasion of the day and left it to quiet church services, visiting parties,

and pleasant family reunions.

It followed the Thanksgiving observance which was first set aside on the third Thursday in

November by President James Madison in 1812, for fasting and thanksgiving on the conduct

of the war against the British. The governor accordingly issued a proclamation inviting

citizens to meet in prayer and fasting in their respective communities.

In 1848 Governor William A. Graham called for an annual Thanksgiving Day, “a season for kind,

social sentiment – for the forgiveness of injuries – for acts of good neighborhood and especially

for the charitable remembrance of the Poor.” The Legislature, in joint resolution ratified the

Governor’s recommendation on 16 January 1849, and authorized the governor to set apart a

day in every year for public thanksgiving and to give notice of it by proclamation.

“Christmas is coming,” wrote the Wilmington Journal on 23 December 1851, and “. . . were it not for

the little and big niggers begging for quarters, and the “noise and confusion” and the “Kooners,”. . .

and the fire crackers, and all the other unnamed horrors and abominations, we should be much

inclined to rejoice thereat. By the by, egg-nog is a most villainous compound to get sober on.”

Eight years later the Journal wrote regarding Christmas . . . “With a good sense that eschews

Blue-lawism, our town authorities on Christmas generally let the boys have their way so far as

mere noise is concerned, although order in all essential particulars is enforced . . . a good deal

of cheering and shouting, but nothing worse, and as the night wore

on even these ceased, and the town slept.”

Christmas on the plantation was usually a very festive annual affair and slaves took the

occasion as a time for celebration. Guion Johnson’s “Antebellum North Carolina” states that

“It is a mistake to assume that the Southern slave had no money and no means of earning any . . .

and the planter often rewarded his slaves for extra work by giving them small amounts of cash.

Planters found that their slaves worked better and were more contented if they had the

means of obtaining small luxuries for themselves, tobacco, molasses, clothing, furniture

for their cabins. It was customary to give slaves small amounts of money at

Christmas as well as other times of the year.

Slaves were normally given considerable freedom on Saturday afternoons, Sundays, and on

general holidays such as the Fourth of July and Christmas. The old custom of the South of a

lady’s keeping off the streets on Saturday afternoon arose from the presence of

great numbers of slaves in town at that time.

Christmas was the holiday slaves enjoyed most as the plantation hands for several days,

and sometimes from Christmas Day until New Year’s Day. Masters were very generous in

these times in issuing passes for journeys to neighboring plantations to visit relatives or

former masters. The slaves would usually have more money at this time than at any other

during the year as the master seldom failed to distribute financial gifts,

as well as presents on Christmas morning.

One of the diversions of the slaves on Christmas Day was called “John Canoeing” in

Edenton and “John Kunering” in Wilmington. The Negroes arose early Christmas morning,

singing their John Canoe songs and shouting “Chris’mas gif” at their masters’ doors.

With liquor on their breaths and money in their pockets, the spent the day in lone long jubilee.

(see more on this custom at: http://www.cfhi.net/JohnKuneringatChristmas.php

Before 1830 it was common for masters to educate their slaves, and especially those who

displayed intelligence and an ability to learn and excel. Most all masters would educate their

slaves in Christianity and encourage Christian habits in their moral and ethical lives.

This was despite the laws after the 1831 Nat Turner massacre in Virginia, in which nearly

70 women, children and old men were hacked to death by Turner and his gang. Turner

had become a black preacher and claimed to have heard voices directing him to his

murderous rampage, hence the barring of slave education after 1831.

The following provide insights to better understand the experience of North Carolinians

and Southerners in general before and during the war. It goes without saying that the war years,

especially after 1863, were times of sacrifice, scarcity and privations.

The Plantation Christmas

“No sooner was the harvest over, than preparations for Christmas began. Whole calves were

barbequed, pigs roasted, while wild game and venison were hunted. For days ahead there

was much cooking of plum pudding, fruit cakes, Sally White cakes, pies and all sorts of

good things, (they make your mouth water to think of them). The big Yule log was brought

in from the swamp the day before Christmas, where it had been soaking for weeks, the alert

darkies knowing that as long as it burned in the “great house” they would stop working.

The mansion was elaborately dressed with evergreens, while branches of dried cedar dried hydrangea

blooms were powdered with flour, making feathery white blossoms, as if in summer time. The holly

tree was ornamented with long strings of popped corn, strung by the white and colored children.

Early Christmas morning the “Great House” was awakened by the singing of the darkies and

voices calling out – “Ch’mas gif’, master, “Ch’mas gif”, mistress.” On the great tree were gifts for

everyone on the plantation. In the low country of the South the Negroes dressed themselves

as clowns, grotesque costumes (being known as “John Kunners”) and marched around ringing

bells, as the danced, singing – “Ch’mas comes but once a year, hurrah Johnnie Kunner –

give poor [Negro] one more cent, hurrah John Kunner.” With the passing of their hats,

pennies were dropped by the “white folks.”

Words fail to express the Christmas dinner of the old plantation. In front of “Marster” was a

roast pig (red apple in his mouth) or the largest gobbler. Innumerable were the desserts or sweet –

syllabub, custard, trifle, wine jelly, cocoanut and lemon puddings, mince pies, every kind of cake,

and Snow Balls especially for the children.

With the dinner, wines were served, made from the plantation scuppernong, James or Catawba grapes,

or from the luscious blackberry. In the quarters was served a wonderful repast to the entire colored

population, and their gayeties were shown in dancing the “double shuffle,” the “break down,” the

“chicken in the bread tray,” and the “pigeon wing,” followed by the “cake walk.” Up in the Mansion

the family and guests probably engaged in the Virginia Reel or other forms of dancing.

Until New Years’ Day, the festivities would continue, a party at every plantation within riding distance,

each house overflowing with merriment. A plantation Christmas would not be complete without a

fox hunt, for “to ride with the hounds” was one of the accomplishments necessary to the planter

and his sons. Space forbids further description of the happiness of life on an antebellum plantation

in the South, but many of our Southern writers have given indelible pictures of the bond between

master and slave, which was unique, will go down as an example of understanding affection.

Without trying to condone the rare case of unkindness from planters toward their slaves,

on the whole they were well treated and the hearts of the two races

were closely knit in the old plantation system.

There was a personal interest in the heart of the planter and his family for these dusky folks

who belonged to them. And they had a pride in their slaves that was reciprocated by them,

who felt that their “White Folks” were better than any others. In writing of the race problem

(after the Sixties) Henry W. Grady of Georgia said: “As I recall my old plantation home,

the spirit of my old Black Mammy from her home above the skies, looks down to bless

me, and through the tumult of the night the sweet music of her crooning, as she held me

in her arms and lead me smiling to sleep.”

One writer says: “The old plantation life is gone, but in that era of the Old South were

found the very finest and highest types of loyalty and of patriotism that America will ever know.”

(Plantation Life in the Old South (excerpt), Lucy London Anderson, The Southern Magazine, May 1934, page 10)

Christmas Cheer on the Plantation:

“The great fete of the people was Christmas. [All] times and seasons paled and dimmed

before the festive joys of Christmas. It had been handed down for generations . . . it had

come over with their forefathers. It had a peculiar significance. It was a title. Religion had

given it its benediction. It was the time to “Shout the glad tidings.” It was The Holidays.

There were other holidays for the slaves, both of the school-room and the plantation, such as Easter

and Whit-Monday; but Christmas was distinctively “The Holidays.”

Then the boys came home from college with their friends; the members of the family who moved

away returned; pretty cousins came for the festivities; the neighborhood grew merry; the Negroes

were all to have a holiday, the house-servants taking turn and turn about,

and the plantation made ready for Christmas cheer.

The corn was got in; the hogs were killed; the lard “tried”; sausage-meat made; mince-meat prepared;

the turkeys fattened, with “the big old gobbler” specially devoted to the “Christmas dinner”;

the servants new shoes and winter clothes stored away ready for distribution; and the plantation

began to be ready to prepare for Christmas.

In the first place, there was generally a cold spell which froze up everything and enabled the

ice-houses to be filled. The wagons all were put to hauling wood – hickory; nothing but hickory now;

other wood might do for other times, but at Christmas only hickory was used; and the

wood-pile was heaped high with the logs . . .

In the midst of it came the wagon or ox-cart from “the depot,” with the big white boxes of Christmas

things, the black driver feigning hypocritical indifference as he drove through the choppers to the

storeroom. Then came the rush of all the wood-cutters to help him unload . . . as they pretended

to strain in lifting, of what “master” or “mistis” was going to give them out of those boxes,

uttered just loud enough to reach their master’s or mistress’s ears where they stood looking on,

while the driver took due advantage of his temporary prestige

to give many pompous cautions and directions.

The getting the evergreens and mistletoe was the sign that Christmas had come, was really here.

There were the parlor and hall and dining-room, and, above all, the old church, to be “dressed.”

The last was a neighborhood work; all united in it, and it was one of the events of the year.

Then by “Christmas Eve’s eve” the wood was all cut and stacked high in the wood-house and on

and under the back porticos, so as to be handy, and secure from the snow which was almost

certain to come. The excitement increased; the boxes were unpacked, some of them openly,

to the general delight, others with a mysterious secrecy which stimulated the curiosity to its

highest point and added to the charm of the occasion.

The kitchen filled up with assistants famed for special skill in particular branches of the cook’s art,

who bustled about with glistening faces and shining teeth, proud of their elevation

and eager to add to the general cheer.

It was now Christmas Eve. From time to time the “hired out” servants came home from Richmond

where they had been hired or had hired out themselves, their terms having been common

custom framed, with due regard to their rights to the holiday, to expire in time for them to spend

the Christmas at home. There was much hilarity over their arrival, with their new winter clothes

donned a little ahead of time, they came to pay their “bespecs” to master and mistis.

Later on the children were got to bed, scarce able to keep in their pallets for excitement; the stockings

were all hung up over the big fireplace; and the grown people grew gay in the crowded parlors. Next morning

before light the stir began. White-clad little figures stole about in the gloom, with bulging stockings

clasped to their bosoms, opening doors, shouting “Christmas gift!” into dark rooms at sleeping elders,

and then scurrying away like so many white mice, squeaking with delight, to rake open the

embers and inspect their treasures. At prayers, “Shout the glad tidings”

was sung by fresh young voices with due fervor.

How gay the scene was at breakfast! What pranks had been performed in the name

of Santa Claus! The larger part of the day was spend in going to and coming from the beautifully

dressed church, where the service was read, and the anthems and hymns

were sung by everybody, for everyone was happy.

Dinner was the great event. It was the test of the mistress and the cook, or, rather, the cooks;

for the kitchen now was full of them. The old mahogany table, stretched diagonally across

the dining room, groaned; the big gobbler filled the pace of honor; a great round of beef held the

second place; an old ham, with every other dish that ingenuity, backed by long experience,

could devise, was at the side, and the shining sideboard, gleaming with glass, scarcely held the

dessert. After dinner there were apple-toddy and eggnog, as there had been before.

There were Negro parties, where the ladies and gentlemen went to look on, the suppers having

been superintended by the mistresses, and the tables being decorated by their own white hands.

There was almost sure to be a Negro wedding during the holidays. The ceremony might be

performed in the dining-room or in the hall by the Master, or in a quarter by a colored preacher;

but it was a gay occasion, and the dusky bride’s trousseau had been arranged by her young

mistress, and the family was on hand to get fun out of the entertainment.”

(The Old South, Essays Social and Political, Charles Scribner’s & Sons, 1892, pp. 174-183)

Christmas Letter to One of His Daughters:

Coosawatchie, South Carolina, December 25, 1861

“My Dear Daughter, Having distributed such poor Christmas gifts as I had to those

around me, I have been looking for something for you. Trifles even are hard to get in these

war times, and you must not therefore expect more. I have sent you what I thought

most useful in your separation from me and hope it will be of some service.

Though stigmatized as “vile dross,” it has never been a drug with me. That you may never

want for it, restrict your wants to your necessities. Yet how little it will purchase! But see how

God provides for our pleasure in every way. To compensate for such “trash,” I send you some

sweet violets that I gathered for you this morning while covered with dense white frost,

whose crystals glittered in the bright sun like diamonds, and formed a brooch of great

beauty and sweetness which could not be fabricated by the expenditure of a world of money.

May God guard and preserve you for me, my dear daughter! Among the calamities of war,

the hardest to bear, perhaps, is the separation of families and friends. Yet all must be endured

to accomplish our independence and maintain our self-government. In my absence from you

I have thought of you very often and regretted I could do nothing for your comfort. Your old home,

if not destroyed by our enemies, has been so desecrated that I cannot bear to think of it. I should

have preferred it to have been wiped from the earth, its beautiful hill sunk, and its sacred trees

buried rather than to have been degraded by the presence of those who revel

in the ill they do for their own selfish purposes.

I pray for a better spirit and that the hearts of our enemies may be changed. In your

homeless condition I hope you make yourself contented and useful. Occupy yourself in

aiding those more helpless than yourself. Think always of your father. R.E. Lee.”

(And to One of His Daughters, Civil War Christmas Album, Philip Van Doren, editor, Hawthorne Books, 1961, page 19)

Christmas After Fredericksburg, 1862

“After the battle of Fredericksburg [December 11-15, 1862] the fine weather, clear,

cold and bracing, which we had been having, changed into a real Virginia winter with a good deal

of the Northern thrown in. It snowed, froze, thawed and rained by turns, with here and there

bright days. All military operations were brought to a close, and both armies went into winter

quarters. The latter part of December was fearful; a long rain followed the battle, then a hard,

bitter freeze came. So intense was the cold that the men did nothing but cower over the fire

piled high with wood night and day….the earth was frozen as hard as granite;

the streams were solid: Ice King held all nature in a relentless grasp.

The Christmas of 1862 was cheerless indeed; the weather was frightful, and a heavy

snowstorm covered everything a foot deep. Each soldier attempted to get a dinner in honor

of the day, and those to whom boxes had been sent succeeded to a most respectable

degree, but those unfortunates whose homes were outside the lines had nothing whatever

delectable partaking of the nature of Christmas. Well! It would have puzzled [anyone] to

furnish a holiday dinner out of a pound of fat pork, six crackers, and a quarter of a pound

of dried apples. We all had apple dumplings that day,

which with sorghum molasses were not to be despised.

Some of the men became decidedly hilarious, and then again some did not; not because

they had joined the temperance society nor because they were opposed to the use of intoxicating

liquors, but because not a soul invited them to step up and partake. One mess in the Seventeenth

[Regiment] did not get so much as a smell during the whole of the holidays;

and a dry, dismal old time it proved.

We read in the Richmond papers of the thousands and thousands of boxes that had been

passed en route to the army, sent by the ladies of Richmond and other cities, but few found

their way to us. The greater part of them were for the troops from the far South who were

too distant from their homes to receive anything from their own families. The Virginians were

supposed to have been cared for by their own relatives and friends;

but some of them were not, as we all know.”

(The Christmas After Fredericksburg, Civil War Christmas Album, Philip Van Doren, editor, Hawthorne Books, 1961, page 23)

“Now I Just Know This Is Christmas”

"Varina Howell Davis, Mississippi-born wife of the Southern president declared, "That Christmas

season was ushered in under the thickest clouds; every one felt the cataclysm which impended,

but the rosy, expectant faces of our little children were a constant reminder that self-sacrifice

must be the personal offering of each member of the family."

Because of the expense involved in keeping them up, Mr. Davis had recently sold her

carriage and horses. A warm-spirited Confederate bought them back and sent them to her. Now she

planned to dispose of one of her best satin dresses to obtain funds; with Christmas on the way,

the children had high expectations, and she would use all possible makeshifts in an effort to

fulfill them. The Richmond housewives could find no currants, raisins, or other vital ingredients

for old Virginia mincemeat pie. But, Mrs. Davis went on, the young considered at least

one slice their right, "and the price of indigestion...

a debt of honor due from them to the season's exactions."

Despite the war, apple trees still bore fruit; with these as a base, she and the other women

of the city would utilize any other fruit that came to hand. A little cider and some salt were

obtained, as was brandy, though its usual price was a hundred

dollars a bottle in inflated Confederate currency.

As for eggnog, the Negro stable attendant, who brought in "the back log, our

substitute for the Yule log," said he did not know how they would "git along without

no eggnog. Ef it's only a little wineglass." Plans progressed for a quiet home Christmas

when unexpected word arrived: The orphans at the Episcopal home had been promised

a tree and toys, cake and candy, plus a good prize for the best-behaved girl,

and something had to be done about that.

Something was done. With Mrs. Davis's help, a committee of women was set up and the

members repaired to their children's old toy collections to salvage dolls without eyes, monkeys

that had lost their squeak, three-legged and even two-legged horses. They fixed and

painted everything, plumping out rag dolls and putting new faces on them,

adding fresh tails to feathered chickens and parrots.

The Davis's invited a group of young friends on Christmas Eve to help make candle molds

and string popcorn and apples for the tree; Mr. Pizzini, the confectioner, contributed

simple candies. For cornucopias and other ornamentation the Davis's guests used colored

papers, bright pictures from old books, bits of silk out of trunks. All in all, the Christmas Eve

of 1864 was far from unsatisfactory. When the small supply of eggnog went around, the

eldest Davis boy assured his father: "Now I just know this is Christmas."

(The Southern Christmas Book, Harnett T. Kane, David McKay Company, 1958, pp. 208-210)

Christmas Vandals in Georgia:

Mrs. Mary S. Mallard in Her Journal [1864, Liberty County, Georgia]

“Monday, December 19th.

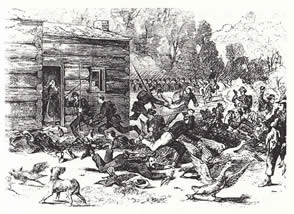

Squads of Yankees came all day, so that the servants scarcely had a moment to do anything

for us out of the house. The women, finding it unsafe for them to be out of the house at all, would

run in and conceal themselves in our dwelling. The few remaining chickens and some

sheep were killed. These men were so outrageous at the Negro houses that the Negro men

were obliged to stay at their houses for the protection of their wives; and in some instances,

they rescued them from the hands of these infamous creatures.

Tuesday, December 20th.

A squad of Yankees came soon after breakfast. Hearing there was one yoke of oxen left,

they rode into the pasture and drove them up…needing a chain…they went to the well and

took it from the well bucket. Mother went out and entreated them not to take it from the well,

as it was our means of getting water. They replied: “You have no right to have

even wood or water,” and immediately took it away.

Wednesday, December 21st. 10 A.M. Six of Kilpatrick’s cavalry rode up, one of them mounted

on Mrs. Mallard’s valuable gray named Jim. They looked into the dairy and empty smokehouse,

every lock having been broken and doors wide open day and night. They searched the

servants’ houses; then the thundered at the door of the dwelling. Mother opened it,

when one of them presented a pistol to her breast and demanded why she dared keep

her house closed, and that “he be damned if he would not come into it.”

She replied, “I prefer to keep my house closed because we are a helpless and defenseless

family of women and children.” He replied, “I’ll be damned if I don’t just take what I want.

Some of the men got wine here, and we must have some.” She told them her house had

been four times searched in every part, and everything taken from it. And recognizing

one who had been of the party that had robbed us, she said: “You know my

meal and everything has been taken.”

He said, “We left you a sack of meal and that rice.”

Mother said, “You left us some rice; but out of twelve bushels of meal you poured out

a quart or so upon the floor---as you said, to keep us from starving.”

Upon one occasion one of the men as he sat on the bench in the piazza had his coat

buttoned top and bottom, and inside we could plainly see a long row of stolen breast jewelry---

gallant trophies, won from defenseless women and children at the South to adorn the

persons of their mothers, wives, sisters, and friends in Yankeeland!”

(The War the Women Lived, Walter Sullivan, J.S. Sanders & Company, 1995, pp. 238-239)

Black Santa's Save Christmas in 1864

"It was a grim hour for all of the South when William Tecumseh Sherman [was] marching relentlessly

through Georgia . . . [and a] young mother has caught much of the pathos of the hour in several

brief entries in her diary. Dolly Sumner Lunt, from Maine, married a planter who lived near

Covington, Georgia. Three years before the start of the war her husband died, and as Mrs. Thomas

Burge, Dolly continued on the estate with her daughter "Sadai" Sarah. The Burge’s were still

there when Sherman's men passed and many of the plantation Negroes, afraid of the soldiers,

slipped into the house to be with their mistress.

On Christmas Eve, Mrs. Burge described her preparations for a bleak meal, her attempts to

provide the plainest of presents for her remaining servants. "Now how changed!" she wrote,

"No confectionery, cakes or pies can I have. We are all sad....Christmas Eve, which has ever

been gaily celebrated here, which has witnessed the popping of firecrackers and the hanging

up of stockings, is an occasion now of sadness and gloom." Worse, she had nothing to

put in her Sadai's stocking, "which hangs so inviting for Santa Claus."

On Christmas night Mrs. Burge penned a sorrowful afternote: "Sadai jumped out of bed very early

this morning to feel in her stocking. She could not believe but that there would be something in it.

Finding nothing, she crept back into bed, pulled the cover over her face, and I soon heard her

sobbing." A moment later the young Negroes had run in: "Christmas gift, Mist'ess! Christmas

gift, Mist'ess!" Mrs. Burge drew the over her own face and wept beside her daughter.

The next year, Christmas came more happily to the Burge plantation. On December 24 [1865]

the mother gave thanks to God for His goodness, "in preserving my life and so much of my

property." And on Christmas Day she added:

"Sadai woke very early and crept out of bed to her stocking. Seeing it well-filled, she soon had

a light and eight little Negroes around her, gazing upon the treasures. Everything opened that

could be divided was shared with them. "Tis the last Christmas, probably, that we shall be

together, freedmen! Now you will, I trust, have your own homes and

be joyful under your own vine and fig tree."

(The Southern Christmas Book, Harnett T. Kane, David McKay Company, 1958, pp. 205-206)

Copyright 2014 The North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission