North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

The Human and Financial Costs of the War

This page helps us pause and reflect upon the human and physical costs of the war, 1861 through 1865.

This was a war which fundamentally changed the Founders’ Union from a republic of sovereign States to

a consolidate union of a centralized government based in Washington, DC, and controlled by a coalition

of States in the Northeast through a political party barely 5 years old at the start of open warfare.

Governor John W. Ellis is April 1861 replied to Lincoln’s demand for troops to invade South Carolina

with an appropriate negative, and stating that the United States Constitution did not arm the President

with such authority; after four years of war in April 1865, the freely-elected government of North Carolina

was replaced with a military regime which answered to the new central authority in Washington.

The Odds and Human Costs:

“…The (Confederate) government (presented) in May, 1864, about 264,000 combatants to Mr. Lincoln’s 970,000,

the number he had under arms at that time. While General Grant…was able to put in the field 620,000

men in May,1864, Mr. (Jefferson) Davis opposed him with about 125,000 in the several active armies.

The disproportion of forces, and the relative character of the rival armies may also be illustrated by

the numbers actually arrayed against each other in several battles.

At the critical turn of the first battle of Manassas (July 21, 1861), the official reports of Generals McDowell

and Beauregard show that the decisive grapple …was made by 6500 Confederates against 20,000

United States troops, including several regiments of regulars. The Confederates won it.

At Sharpsburg, 33,000 Confederates repulsed 90,000 Federalists. At Chancellorsville, 35,000 Confederates

beat General Hooker with the “finest army on the planet.” In the Wilderness, General Lee met General

Grant’s 142,000 with 50,000…In the battle on Winchester in the autumn of 1864, Sheridan won a dearly

bought victory from General Early by hurling 50,000 upon (Early’s) 12,000. In the closing struggle

General Lee’s 33,000 were not dislodged from Petersburg and Richmond until their assailants were

increased to 180,000.

And finally, the remnant of Lee’s heroic army did not surrender to this enormous host until it was reduced

to less than 8,000 muskets. The aggregate of men paroled at Appomattox was made up of some twenty

or more thousand stragglers and men on detached service who came in, to avail themselves of the

supposed pacification after the termination of military operations.

(Discussions by Robert.L. Dabney, S.B. Ervin, 1897, pp. 130-131.)

“We were outnumbered by over 2-1/4 millions. To put it another way they had 4-2/3 men to our one.

Of the millions against us were 494,000 men were foreigners. This number only fell short of our entire

number 110,000, and was more than made up by the 186,017 colored soldiers enlisted in the Federal army.

So my comrades, it will be seen that we were outnumbered by foreign and colored soldiers, and had to

contend against a surplus of 2,203,215 loyal patriotic soldiers of our own country. New York, Iowa and

Connecticut furnished more men than were in our entire army. They had an army, a navy and

ordnance to begin with, while we had neither. They had money and credit abroad, but we had none.

And yet, in spite of all these things, it took four long years for the North to overpower the brave South.

History presents no grander page than written by the Confederate soldier. We have the right to point our

children and the young people of today to the sanguinary conflict which we have passed through, and teach

them that their fathers were not traitors, but brave patriotic soldiers.

The Confederate went to battle at the call of his State; he recognized its authority as supreme.

We believed we were right and have not changed our minds, you believed you were right, and are of

the same opinion still. We cannot agree on this question, but since the close of the war the Confederate

soldier has been true to that starry flag, and is ready to follow it with the same patriotic heroism which

he followed that one with its stars and bars, which flag was ours. We stained it with our blood,

we upheld it as long as we could; we love it yet (and) we love the memories that cluster around it…”

(Hon. A.G. Hawkins, Confederate Veteran, October, 1895 page 313)

“The war cost the life of one soldier, Rebel or Yankee, for every six slaves freed and for every ten white

Southerners saved for the union. (Potter, 261). The money spent to field the two armies would have

purchased the liberty of the four million slaves five times over.” (Tombee, Portrait of a Cotton Planter,

Theodore Rosengarten, Morrow & Company, 1986, page 212.)

“Lincoln’s war ended up costing 620,000 battlefield deaths along with the death of some 50,000 Southern

civilians, including thousands of slaves who perished in the federal bombardment of Southern cities

and because of the devastation of the Southern economy. By 1865, the Lincoln government had killed

one out of every four Southern white males between the ages of 20 and 40.”

(The Culture of Death, Dr. Thomas DiLorenzo, 2001.)

“…2,326,168 men of the North and 750,000 Southerners took part in the struggle.

Of these, according to Fox’s estimates in the Photographic History, Vol. X, the North lost 259,000 men

killed in the field and died of wounds and disease; and the South lost 135,000 all told. In this stupendous

conflict, therefore, the loss aggregated nearly half a million lives lost and ruined in the armies, and even

a greater number of Negro lives caused by neglect, disease and starvation, making a total of upwards

of a million human lives. Not only this, but the women and children on both sides suffered miseries.

Then at the South there was a desolation of ruin and poverty estimated in the long run

at twenty billions of dollars.”

(A Southern View of the Invasion of the Southern States, Captain S.A. Ashe, 1935, page 64.)

General Robert E. Lee knew the ragged, half-starved, barefoot and poorly-armed American soldiers

under his command would not fail him against overwhelming odds, they performed admirably time

after time. This was America’s greatest military man, and men.

“There was a Confederate scout, Stringfellow by name, who on the 4th of May, 1864, the eve of the

opening of that [Wilderness] campaign, reported himself to [General] Lee, when the

following colloquy took place:

“Well, Captain Stringfellow, where do you come from?”

“From Washington, General.”

“What number of men has General Grant, and what is he doing?”

“He has about 140,000 men in front of you and is about to move on you.”

Without a moment’s hesitation Lee said: “I have 54,000 men up, and as soon as

he crosses the river I will strike him.”

Grant crossed the Rapidan on the following day, and as soon as he was entangled in the

Wilderness Lee struck him a staggering blow. In the four weeks’ campaign ending with Grant’s

bloody repulse at Cold Harbor on June 2…Lee had put as many of Grant’s men out of action as

he himself had under his command during the entire campaign – viz., 64,000.”

(Robert E. Lee, H. Gerald Smythe, Confederate Veteran Magazine, January 1921, pp. 6-7)

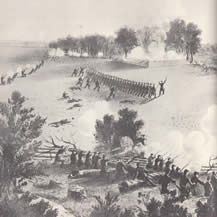

Americans Facing Overwhelming Odds:

“In this final carnage, (General Joseph) Johnston had at his entire command some fifteen-thousand

available men, while Sherman opposed him with an army seventy-thousand strong, flushed with victory.

On the morning of March 20 [1865] it was reported that the Federal right wing had crossed over to unite

with the left wing which had been driven back and was coming up rapidly upon the

left of [General Robert F.] Hoke’s division.

From noon to sunset Sherman’s army, now united, made repeated attacks upon Hoke’s division

of six-thousand men and boys, but were uniformly driven back. The skirmish line of the brigade and the

center were commanded by Major Walter Clark. The battle raged through March 20 and 21. The night

of the 21st the Confederate army re-crossed the creek by the bridge near Bentonville [North Carolina].

The Federals made repeated attempts to force the passage of the bridge, but failed. The Confederate losses

in the battle of Bentonville were 2343, while those of the Federals were nearly double that number.

No bolder movement was conceived during the war than this of General Johnston, when he threw his

handful of men on the overwhelming force in front of him, and when he confronted and baffled his foes, holding

a weak line for three days against nearly five times his number. For the last two days of this fight, he held

his position only to secure the removal of the wounded. The Junior Reserves lost a number of officers

and boys in this battle. General Hoke later wrote of the Junior Reserves:

“The question of the courage of the Junior Reserves was well established by themselves in the battle below

Kinston and at the Battle of Bentonville. At Bentonville they held a very important part of the battlefield in

opposition to Sherman’s old and tried soldiers, and repulsed every charge that was made upon

them with very meager and rapidly thrown up breastworks. It was equal to that of the old soldiers

who had passed through four years of war. I returned through Raleigh, where many passed by their

homes, and scarcely one of them left their ranks to bid farewell to their friends, though they knew not

where they were going nor what dangers they would encounter.”

(Walter Clark, Fighting Judge, Aubrey Lee Brooks, UNC Press, 1944 pp. 20-21)

The Grandest Soldiers That Ever Marched:

"Yes, the Northern army was a fine one, well equipped and well officered, with all the resources at

hand that could be desired for great and aggressive warfare; but it had to meet an army of Southern

troops composed of the grandest soldiers that ever marched to martial music, or fought in defense of country!

Just to think, that the Southern army of six hundred thousand men, poorly armed and equipped,

ridiculously clad and meagerly fed, without tents, without medicine, without pay, checkmating,

baffling, repulsing and often humiliating and disastrously defeating the Northern army of 2,778,304

men armed with the most improved engines of warfare, well paid, well fed, abundantly clothed;

backed by all the resources of a great nation, for four long, dreary years,

staggers the credulity of man to contemplate.

In a letter to General [Jubal] Early shortly after the close of the war, General Robert E. Lee wrote:

“It will be difficult to get the world to understand the odds against which we fought.”

From the number drawing pensions from the United States government today, fifty years

since the close of hostilities, there might have been a million more soldiers in the

Union Army than given in the figures named above.”

(Sketch of the War Record of the Edisto Rifles, William V. Izlar, The State Company, 1914, pp. 98-100)

Grant, the Butcher

"Here, we thought that Grant would certainly have had enough for the season, but shortly we again we found

ourselves making a forced march to cut him off at Cold Harbor, where we formed our lines and had some

terrible fighting. It was at Cold Harbor that Grant earned his title of “Butcher,” and deserved it. He hurled

his troops time after time against our men in earthworks from which he could not have driven them with

the whole Yankee nation to back him. How many men he sacrificed will, I suppose, never be told,

but the ground in front of our works was covered black with the dead, besides the thousands

who were carried off of made their way back, wounded. He never stopped till his men, themselves,

refused to be longer uselessly slaughtered.”

(The Haskell Memoirs, John Haskell, Govan & Livingood, editors, G.P. Putnam’s sons, 1960, pp. 67-69)

Incomparable American Soldiers:

"So much has been said about the morale of the Army of Northern Virginia after the Battle of Gettysburg...

and to say nothing about the splendid fighting of A.P. Hill's men and the cavalry at Ream's Station

in August 1864, and the almost daily fights that W.H.F. Lee's cavalry had along the Boydton

Plank Road and the Weldon Railroad at Ream's Station, we swept Hancock's celebrated

2nd Corps away from our front like the whirlwind.

Nothing stopped us and our force was far inferior [in number] to theirs....General A.P. Hill sent...

for a mounted man who was familiar with the country, and he [Lt. Aldrich] was sent. When he

reported to General Hill, the General said: "Lieutenant, how many men have you with the cavalry?"

Lieutenant Aldrich told him that he had about two thousand and then asked: "General Hill, how many men have you?"

The response was: "About eight thousand, I think."

Then the General said: "How many men do you think are in front of us Lieutenant?" To which

the Lieutenant replied: "All of Hancock's troops, I should say about twenty thousand men."

Lieutenant Aldrich then insinuated that the General was attempting a big job with the force

he had. General Hill then said:

"Lieutenant, if we cant whip them with this proportion we'd better stop the war right now."

History shows well how he figured. General Hancock, when he returned from the hospital testified to the

completeness of [his] defeat and told his Corps that the Confederate army could

not be beaten, but must be worn out."

(The Battle of Five Forks, David Caldwell, Columbia, SC, Confederate Veteran Magazine, March 1914, page 117)

The Financial Cost:

“The direct financial cost of the operation of the American [War Between the States] was about $8,000,000,000.,

which, with destruction of property, derangement of the power of labor, pension system and other economic losses,

is increased until the total reached thirty billions of dollars.”

(The Awful Cost of War, Confederate Veteran Magazine, page 389)

“Total cost of all expenses of the Civil War, actual cost of military and naval operations was

$6.2 billion. The direct outlay of the United States Government in the four years of Civil War was $3.4 billion.”

(History of the Spanish-American War, Henry Watterson, Peoples Publishing, 1898, page 578)

Grand Army of the Republic Pension Corruption

"By 1893 there were almost a million [Northern army] pensioners, receiving over $156 billion annually,

or almost a third of the entire expense of operating the government. That inveterate reformer Carl Schurz

called the pension system "a biting satire on democratic government. Never has there been anything

like it in point of extravagance and barefaced dishonesty."

The pressure exerted by the GAR and the political dynamite in the pension question had continually

precipitated more generous pension legislation. Furthermore, the lax administration of the pension laws

allowed applicants with the weakest possible claims, as well as some who were guilty of

"wholesale and gigantic frauds," to be admitted to the rolls. In May 1893, [Hoke] Smith...

revoked the notorious "Order No. 164" [of] 1890...an interpretation [by Republican Commissioner

of Pensions Raum] which proved highly advantageous to person with minor disabilities not of service

origin. During the second Cleveland administration, the spiraling cost of the Federal pensions was

checked...[but] it was in Congress that fundamental pension policy was determined and the

Congressmen were in a liberal mood as far as the [Civil War] veterans were concerned."

(Hoke Smith and the Politics of the New South, Dewey Grantham, Jr., LSU Press, 1958)

Old Grand Army Bummers and Their Pensions

"The assumption behind the original pension law of 1862 had been that the Federal government...

was liable only for injuries...sustained while in [service]. Mere service as a Union veteran did not entitle

a man to any special consideration, even if he happened to be sick, jobless or destitute. By far the

most common rebuttal [to pension reform] involved the declaration of a new principle: that the Union

veteran had a prior claim on the nation's treasury, not as a compensation for illness, not as a gratuity,

but as an absolute right.

The Service Pension Association's Frank Farnham, calling the GAR "the representatives of those who saved

the country, by the greatest of sacrifices," argued that "any reasonable demand" of the veterans should

receive the public's "unqualified support." Opposition to the Grand Army, he said, came mostly from

the ex-Confederates, ex-Copperheads and Mugwumps. New York supporters of the $8 service pension

bill were even more blunt. "The GAR," they proclaimed in 1886, "own this country by the rights of a conqueror."

["Nation" editor Edwin] Godkin...found service pensions appalling in principle. As Congress was considering

a proposal to pension all veterans over the age of sixty, he wrote: "A large proportion of the half-million people

who are added to the pension roll are persons who have no possible claim to consideration. Some of them

were worthless as soldiers during the war; others are now "hard up" simply because they have grown shiftless

and dissipated since the war; others are well-to-do and in no possible need of any increase to their income.

The simple fact about the matter is that any old "bummer" who can establish the fact that

he was connected with the Union Army in any way for ninety days, even if he got no further than the

recruiting camp, may now have his name placed on the pension roll and draw

$8 a month for the rest of his life."

(Glorious Contentment The Grand Army of the Republic, Scott McConnell, UNC Press, 1992)

North Carolina's Losses Severe:

In the battle [Gettysburg] of the first day, Captain Tuttle’s company [of the 26th North Carolina] went

into action with 3 officers and 84 men; all of the officers and 83 of the men were killed or wounded.

On the same day, and in the same [Pettigrew’s] brigade, Company C of the 11th North Carolina lost

2 officers killed and 34 of 38 men killed or wounded. Captain Bird of this company, with the 4 remaining

men, participated in the charge of the 3rd of July [Pickett’s] and of these the flag-bearer was shot, and

the Captain brought out the flag itself. The loss of the 26th North Carolina at Gettysburg was the

severest regimental loss during the whole war.

(Deaths in the Confederate Army, Confederate Veteran Magazine, page 434.)

“…Major [Henry] Grady of Georgia, with 250 of the 25th North Carolina regiment and a remnant of the

26th South Carolina stood between Grant’s army and the city of Petersburg for two long hours, until

[General] Mahone brought reinforcements; how, with that handful of brave Carolinians, he held back

fourteen regiments of federal troops…how he led the gallant charge which, after a hand to hand fight drove

the enemy from our works with a loss of 6,000, and fell mortally wounded just as victory

perched on our banners. (Confederate Veteran, November 1893, page 326)

“Of the 111,000 offensive troops supplied by the State and organized into 72 regiments, all were volunteers

except about 19,000 conscripts. Reserve and Home Guard units brought the grand total up to 125,000 men,

a larger number than the State’s voting population.

In the entire war 19,673 North Carolina soldiers were killed in battle. This was more than one-fourth

of all Confederate battle deaths and moreover, 20,602 died of disease. This total loss of 40,275 was

greater than any other Southern States.

North Carolina furnished the Confederate States with 2 Lieutenant-Generals, 8 Major-Generals and

26 Brigadier-Generals. Notable naval officers from North Carolina were Captain J.W. Cooke of the

ram Albemarle, Captain J.N. Maffitt of the cruiser Florida, and Captain James Iredell Waddell of the

Shenandoah which cruised the Pacific and Arctic waters destroying more union commerce than any other

Confederate ship except the Alabama. No State contributed more to the Southern cause in men,

money and supplies.

(The Civil War in North Carolina, John G. Barrett, UNC Press, 1963, pp. 28-29.)

Compilation of Historical Statistics:

The seceding States in 1861 had a population of 8 million, about 4 million of whom were slaves; the non-seceding

States, 24 million. At the date of surrender the armies stood:

United States, 1,000,516; the Confederate States, 272,025.

Total enlistments in Union army: 2,778,304.

Of that number, black enlistments: 182,000

Of that number, German enlistments: 176,800

Of that number, Irish enlistments: 144,200

The number of Confederate soldiers in Northern prisons, 220,000; the number of Northern soldiers in Southern

prisons, 270,000. The death rate in Northern prisons was 12%, in Southern prisons it was less than 9%.

These prison statistics are taken from the report of Secretary Stanton made July 19, 1866, and corroborated

by the report of Surgeon-General Barnes the following June.

(Confederate Veteran Magazine, November 1897, page 561)

Interesting War Statistics,

Over 250,000 (of the 2,326,168 Northern soldiers) were discharged for disabilities arising from wounds or diseases

which unfitted them for further service. The reported desertions during the war numbered 268,530.

Only 61% of the military (age) population of the loyal States served in the army and navy.

(Confederate Veteran Magazine, page 432)

Copyright 2012, North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission