North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

North Carolinians Among the "Immortal 600"

Memorial at Fort Pulaski Near Savannah

In mid-1864 Northern forces had laid siege to the city of Charleston after obtaining a foothold on Morris Island.

From this point artillery batteries had been erected in order to throw shells not only toward Forts Sumter

and Moultrie, but also the city itself and its noncombatants. This bombardment recalled the April, 1780 siege

of Charleston by British and Hessian forces and was the primary reason why Forts Sumter and Moultrie

were erected in the post-Revolutionary period – to defend Charleston from enemy attack from the sea.

The three highlighted paragraphs below describe the British-Hessian bombardment of Charleston in 1780. Ironically,

soldiers in the invading Northern forces were of German birth and posibly descendants of the earlier Hessian invaders.

Note:

Please see the website www.600csa.com for more information about the Immortal Six Hundred.

North Carolinians of “The Immortal 600”

“Obsessed with the reduction and capture of Charleston, the Northern commander in May 1864, the fourth

in four years who tried to capture the city, planned a massive artillery bombardment to force its capitulation.

His five-pronged attack which coordinated land and sea forces in late June ended in failure, capped by a

Southern counterattack which nearly annihilated the attackers, being saved from this by Northern

gunboats covering the retreat.

“At 10 o’clock in the morning of [April 13, 1780] our batteries began to play violently and seriously

on the city, and this fire was answered just as violently by the enemy. It lasted without interruption until

eight o’clock in the evening. Also, firebombs were shot into the city today, because of which the city, and,

indeed, the house of the governor and of the commanding officer were set on fire as soon as these

bombs began to be used. The Hessian artillery fired the fire-bombs. The enemy works suffered great

damage today, and several of their cannons were dismounted.

(The 1780 Siege of Charleston as Experienced by a Hessian Officer)

General Sam Jones

Commander, South Carolina District

Beyond bombarding Fort Sumter, Northern shells were being thrown indiscriminately into residential

areas of the city. It was claimed that Charleston was a “depot for military supplies, munitions factories and

foundries for war materiel,” and though Charleston’s commander, Major-General Sam Jones, sent

communiqués indicating the presence of non-combatants in the residential sections of the city.

Further, 50 high-ranking Northern officers were quartered in the home owned by

Colonel James O’Conner, what is now 180 Broad Street. These were five generals, forty-five colonels,

lieutenant-colonels, and majors who had arrived in early June. They had been in Charleston when

the increase of bombardment began.

"On the 14th the cannon fire was moderate on both sides. At noon we received news that the

Cathcart Legion and Ferguson’s Corps had attacked a corps of rebels thirty miles from here between

the Cooper and Ashley rivers and captured a hundred prisoners, including three officers, and almost

as many horses. A reinforcement arrived from New York. This consisted of the regiment von Ditworth,

the 42nd Scots Regiment, the Queen’s Rangers, Lord Rawdon’s Corps, and Colonel Brown’s Corps."

(The 1780 Siege of Charleston as Experienced by a Hessian Officer)

Hoping to appeal to the Northern sense of honor and humanity, General Jones notified his opponent

in August that no military targets were located in that residential area of the city. The reply was

“Charleston must be considered a place of arms…In reference to the women and children of the bombarded city,

I therefore can only say the same situation occurs whenever a weak and strong party are at war.”

General Jones was shocked by the reply and determined that this was simply “a threat to destroy

a civilian city in a dishonorable attempt to force a surrender.”

O'Conner House Where Northern Officers Were Held

Jones noted that only civilians were being harmed and killed while those manning the batteries that

would be considered military targets went about their business without drawing the fire of Northern artillery.

"The besieged in Charleston were now cut off from land on all sides [and] we became absolute masters

of the river. On the [May] 7th our siege was continued…Our jaegers caused great damage to the

enemy in the city….a battery did great and constant damage to the houses in the city…

The fire from this battery distinguished itself through the repeated pauses of all other batteries,

and it was not seldom that these Jacktars gave a full broadside.”

(The 1780 Siege of Charleston as Experienced by a Hessian Officer)

As a form of retaliation for Northern officers being in Charleston, fifty imprisoned Confederate officers

were “placed under fire…placing twelve to fifteen officers in the barracks to be constructed in each of the

Union forts, thus protecting the whole Union force on Morris Island.”

To underscore the non-combatant area of Charleston in which they were quartered, the five Northern generals

in Charleston sent a letter to the Northern commander that “[We] at this time, are as pleasantly and comfortably

situated as is possible for prisoners of war, receiving from the Confederate authorities every privilege that we

could desire or expect, nor are we unnecessarily exposed to fire.”

More Southern officers were sent as hostages from Fort Delaware prison, to include Brigadier-Generals

Basil Duke and Franklin Gardner, and Lieut.-Col. Marshall J. Smith. On August 20, six-hundred Southern officers

of all ranks we sent to Morris Island about the steamer Crescent City to be held in an open stockade in front

of the Northern batteries.

General Basil Duke

Captain John C. Gorman [Wilson County] of the 2nd North Carolina Regiment wrote that “We were packed as thick as we

could lie [below decks]…it was a perfect hell, and nearly as hot. The water that was given us was impure, and

some times the stomach would refuse it from its putrid smell. They fed us twice daily, on crackers and raw bacon.”

Other prisoners stated that “at one time we had no water for forty hours…We were almost famished, provisions

and water having given out two days before we reached Hilton Head.

Captain Walter MacRae of the 7th North Carolina Regiment wrote: “On the 7th of September we disembarked

at Morris Island and when we finally came out into the light of day and had a look at one another we were

astonished to note the ravages made by the terrible heat and the nauseous confinement. One could scarcely

recognize his best friends. There were six of us from Wilmington…all badly damaged.”

The rumors of the officers being put in the line of fire had become fact as they saw the stockade pen and had

never thought that a civilized nation would use prisoners as human shields. They would be held there for forty-five

days with artillery fire from their own batteries screaming over their heads and threatening immediate death.

Additionally, a battery of Billinghurst-Requa machine guns were trained on the camp in case the

prisoners became unruly.

A North Carolina Colonel and veteran of the Mexican War, John Lucas Cantwell of the 51st and 3rd North Carolina

Regiments became the official historian of the 600 while confined on Morris Island. He recorded and noted the

sick and wounded, and gathered names and units of the prisoners.

Colonel John Lucas Cantwell

On the evening of September 9th an artillery duel between Morris Island and Fort Moultrie occurred, and

most of the firing would be at night. The gunners at Moultrie fired well but occasionally a shell would

burst overhead and scatter fragments in the camp. The greatest danger to the prisoners came from the

Northern batteries behind them as shells fired could burst prematurely – and throw huge shrapnel into the

camp. After one of these incidents a horse was killed by fragments and a man’s leg sliced off.

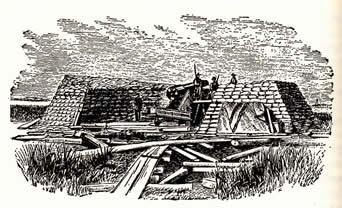

Northern Siege Gun, the "Swamp Angel"

One night “the whole heavens were illuminated and the mortar shells were darting through the heavens

in all directions as though the sky was full of meteors."

On September 10, General Jones in Charleston wrote the Northern commander that he had received

word that numerous Confederate officers were under fire from Sumter “because I believe you are

retaliating on those officers for a supposed disregard of the usages of civilized warfare in the

treatment extended to U.S. officers, prisoners of war, now in this city. Those officers are comfortably

housed and receive the treatment due prisoners of war.” He urged his opponent to bring his actions

within the confines of accepted rules of war.

Though the Northern officers in Charleston had little complaint of their prison fare of fresh meat, rice,

bread, meal and beans, the rations accorded the Confederate officers would barely sustain life.

Captain MacRae recored that “Some of the prisoners for the sake of the record complained to the

[Northern] colonel. He replied that it was all right; there was meat enough in the meal, bugs and worms,

and that if he had his own way he would be only too glad to feed us on greasy rags.” A Virginia captain

wrote about “the amount of dead animal matter in the shape of white worms, which was the mush given us.”

Another said they received “one-half pint bean soup, two crackers, wormy and full of bugs. Rations for

supper, two ounces of bacon, two crackers, wormy as usual.” The daily ration would change about three

weeks later, altered to one-quarter of the previous amount – resulting in severe weakness and intestinal

disorders in the prisoners. Water ration was cut as well, and the men began to catch rain or dig for water.

A Virginia officer said “they are starving us by degrees.”

After being under fire for three weeks, the first prisoner died – of starvation. Lt. William P. Callahan

of the 25th Tennessee cavalry officially died from chronic diarrhea and was buried at Morris Island.

On October 2, 1864, Lt. Frank Peake died of the same –a condition brought on by poor diet and

unsanitary living conditions. Passing from a wound that his diet could not help heal as well as

pneumonia, was twenty-two year-old John C.C. Cowper of the 33rd North Carolina Regiment.

He had been wounded and captured at Gettysburg over a year before.

Due to an outbreak of yellow fever in Charleston in late September, General Jones was forced to move

his Northern prisoners to safety in Columbia. He notified Morris Island on October 13 that no

Northern officers were confined in Charleston, though this was ignored and the shelling of the city

intensified. With retaliatory fire from the Charleston batteries replying in kind, many Northern troops

abandoned the prisoners inside the pen. Unmoved that their indiscriminate firing was killing civilians,

Northern gunners threw a shell into the city every fifteen minutes.

At the end of October the authorities in Washington ordered an end to the bombardment of Charleston and

Northern troops were to take up defensive positions instead. From their original number of 600 upon

departing Fort Delaware, they now numbered five-hundred forty-nine – and had been under fire in their

stockade for forty-five days.

The six-hundred were moved on to transports and taken to Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River.

Here they experienced more civilized guards and rations, though an early winter and exposure broke the

health of many officers – many caught colds and pneumonia. Many others had yet to recover from the

unsanitary conditions at Morris Island and long-term effects of the poor diet.

Fort Pulaski

Though food rations had improved, Christmas arrived and found many in the depths of depression,

tired of hoping for exchange or parole. It was too cold to walk around the prison barracks to relieve the

monotony. A Virginian noted that “Our rations are worse now than ever, our bread rations are being cut

down still lower and a few pickles being given us, which only increases our appetites for food which we

are not allowed to have. We have suffered most intensely from the cold during the last few days.”

Captain J. Ogden Murray of the 11th Virginia Cavalry wrote “I recall the dreadful sights and misery in that

Fort Pulaski prison – loved comrades starving to death, dying with that terrible disease scurvy, and the great

government of the united States responsible for all this wanton cruelty; and yet no effort was made to alleviate

or curtail it. Who will ever forget grand old Capt. John Lucas Cantwell – Gentle, kind, true…One thing that often

impressed me was the heroic conduct of our men under the ordeal…some of our comrades would…sing the

old familiar songs of the South, seeming for a time to forget the pains of retaliation and their hunger.”

Josyln writes or the physical result of their long confinement, starvation diet and physical deterioration:

“Young men, once vigorous, lay prostrate with the diseases of old age – rheumatism, pneumonia, and bronchitis.

The sound of coughing and labored breathing filled the room, disturbing the sleep of all. Scurvy and dysentery

existed in the extreme, causing debility and making life unendurable. In advanced stages, as many officers had it

by the end of January 1865, scurvy symptoms are similar to those of hemophilia. The blood vessels simply

disintegrate, spilling blood into the body. The joints are particularly affected, as the blood swells them and

prevents movement, causing excruciating pain. Most become blind to some degree, their palid faces like

ghosts from the anemia induced by scurvy. In the harsh conditions they clung

to each other for comfort, suffering patiently.”

Captain Murray of Virginia recalled “When the wolf, hunger, takes hold of a man, all that is human in the

man disappears. He will, in his hunger, eat anything. It is impossible to explain how we lived through

the terrible ordeal of fire and starvation. Those were horrible days – days which most thoroughly convince

me that nothing but actual experiment can determine how much starvation, hunger,

and bad treatment a human being can stand.”

Another Virginian wrote on January 2, 1865: “Yesterday…was the coldest day of the winter, which the

Yanks celebrated by refusing to furnish any wood. All day and all night many of us walked to keep up

the circulation, or shivered in our scanty covering. It was so cold that the boys who had no blankets had

to walk all night to keep from freezing.”

Capt. Henry Dickinson of the 2nd Virginia Cavalry wrote on February 1, 1865:

“On the 28th inst. Lieutenant [John M.] Burgin, of [the 22nd ] North Carolina, died from dysentery

at the hospital. Over 100 men are now sick, and scurvy in its worst form is among us…the scurvy sores

on the bodies of those around me are terrible sights.”

Many of the six hundred were shipped north and re-imprisoned at Fort Delaware in mid-March 1865.

At the ship’s arrival, seventy-five could not walk and had to be carried ashore – and many were

emaciated and near death after the sea journey from Georgia.

Adjutant Francis A. Boyle, 32nd North Carolina Regiment wrote on Wednesday, 15 March 1865:

“Their sufferings have been awful. By way of retaliation they were kept upon one pint of miserable wormy sour meal

and pickles per day for 45 days. Some actually starved to death upon this diet. Many others have been afflicted

with scurvy in its worst form, some still dying from its effects, and all whom I have seen show their bad treatment

plainly. At one time half their number were unable to rise from their beds. This diet was continued even after

many had been sent to the hospital in little better than a dying condition…”

After the fall of Richmond and Lee’s surrender at Appomattox in early April, many of survivors discussed

how the Northern government would treat them – as traitors and face execution? As expected, most would

refuse an oath of allegiance to what they considered a foreign government. They had reached a point where

they no longer had a country. But to many, “swallowing the dog” would release them to walk the long journey

home to family and hearthside

After Lincoln’s assassination reached Fort Delaware, the guards became mad and vindictive and

prisoners wondered “how many Southern lives it would take to appease the wrath and vengeance of the North.”

The prisoners were refused mail and word was passed that any sign of joy at Lincoln’s death would result

in immediate execution. As usual, boxes of goods sent to the prisoners by family and friends would be confiscated

and used by prison officials.

In late April and early May prisoners were repeatedly requested to take an oath of allegiance to the Northern

government, despite their sworn oaths to their home States. By the end of May and the life of the Confederate

government ebbing, and sensing their duty was to be home supporting their families and farms, only 161 of 2300

officers held in Fort Delaware refused the oath. Those that refused would continue imprisoned with sickness

and starvation their companion – and struggle with the thoughts of being home with their loved ones.

Fort Delaware

Most of the prisoners had taken the oath by June 1865 and all captains and lieutenants allowed to leave. No provision

for transportation was allowed and the sick, emaciated figures left the cold walls of the prison for the long walk home.

Colonel Tazewell Hargrove of the 44th North Carolina Regiment had steadfastly refused the oath as did

the remaining field-grade Confederate officers still held. After a letter from home from his father and a compatriot,

Hargrove and the rest relented after General Lee’s instructions to take the oath and help rebuild the devastated South.

He and the others were released on 24 July 1865.

After war’s end, John Lucas Cantwell returned to Wilmington and in 1866 formed the first organization of

Southern veterans -- the 3rd North Carolina Infantry Association. Fellow Wilmingtonian Captain Walter MacRae

later applauded Cantwell’s actions with this:

“the many attempts at escapes, always betrayed, the sickness, the wounds, the deaths, the organized efforts

for mutual help…are they not written and minutely set forth in Col. John L. Cantwell’s book of statistics and

notes which he began to collect from the start…even to the present day and which he preserved….Heaven

knows how, amid all the chances and changes of our prison life, so that it furnishes the only authentic statement

of those trying times which is now extant…Glancing over this little book, the eye rests on this pathetic sentence:

“Was not allowed to mark the graves of brother officers at Fort Pulaski, though headboards were prepared

(by the prisoners) for all the dead.” What need of any further comment.”

It is believed that the order from above to place the Southern officers under the fire of their own guns came

from Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton.

Source: Immortal Captives, The Story of Six Hundred Confederate Officers and the US Prisoner of War Policy,

Mauriel Phillips Joslyn, White Mane Publishing, 1996,

Flag of North Carolina

Roster of North Carolinians:

“Of the 600 Confederate prisoners sent to Charleston for exposure to the fire of their own artillery,

111 were North Carolinians. The list below has been provided by Col. John Lucas Cantwell of Wilmington, and the

few omitted had disgraced themselves by committing treason and taking an oath to the Northern government.

Abernathy, S.S., Wake County

Alexander, W.J., Wilkes County

Allen, W.B., Wake County

Allen, T.M., Fair Field

Allison, M.B., Webster

Albright, G.N., Melville

Andrews, H.C., Orange County

Anderson, W.T., Fayetteville

Avant, G.W., Chatham County

Barrow, T.P., Washington

Brown, Alex. H., Longstreet

Blair, J.A., Macon County

Blair, J.C., Boone

Bloodworth, J.H., Wilmington

Blue, E. McN., Moore County

Bohannon, S.S., Yadkin County

Bradford, N.G., Lenoir County

Bromly, C.R., Concord

Brothers, J.W., Kinston

Burgin, J.M., Marion

Bullard, D.S., Owenville

Bullock, Jno. T., Tranquility

Birkhead, B.W., Asheboro

Busbee, C.M., Raleigh

Cantwell, Jno.L., Wilmington

Carr, Robt. B., Duplin County

Carver, E.A., Forestville

Chandler, W.B., Yanceyville

Coffield, J.B., Tarboro

Coggin, J., Montgomery County

Cockerham, D.S., Yadkin County

Cole, Alex. T., Rockingham

Coon, David A., Lincolnton

Cooke, George S., Graham

Cowan, Jno., Wilmington

Coble, George S., Graham County

Cowper, J.C.C., Murfreesboro

Crapon, Geo. M., Smithville

Crawford, T.D., Washington

Darden, J.H., Snow Hill

Day, Wm. H., Halifax

Davis, A.B., Wilson

Dewar, W.A., Harnett County

Dixon, H.M., Moore County

Doles, W.F., Nash County

Earp, H., Johnston County

Elkins, J.Q., Whiteville

Fennell, Nicholas H., Sampson County

Floyd, F.F., Leesville

Folk, G.N., Morganton

Fowler, H.D., Rolesville

Frink, J.O., Cerro Gordo

Gash, H.Y., Hendersonville

Guyther, Jno. M., Plymouth

Gamble, J.F., Shelby

Gordon, W.C., Morganton

Gowan, B.A., Whiteville

Gurganus, J.A., Onslow County

Howser, A.J., Lincolnton

Harget, J.M., New Bern

Hargrove, T.L., Oxford

Hart, E.S., Bostick’s Mill

Hartsfield, J.A., Rolesville

Hartsfield, L.H., Kinston

Heath, J.F., New Bern

Henderson, T.B., Jacksonville

Henderson, L.J., Onslow County

Hines, Jno. C., Clinton

Hines, S.H., Milton

Highly, G.P., Lumberton

Hobson, J.M., Rocksville

Horne, H.W., Fayetteville

Ivy, W.H., Jackson

Jenkins, H.J., Murfreesboro

Jones, W.T., Moore County

Johnson, Wm. P., Charlotte

Johnson, T.L., Edenton

King, J.E., Onslow County

Kitchin, W.H., Scotland Neck

Knox, J.G., Rowan County

Kyle, J.K., Fayetteville

Lane, C.C., Snow Hill

Lane, J.W., Hendersonville

Latham, J.A., Plymouth

Lindsay, G.H., Madison

Lindsay, J.B., Wadesboro

Leatherwood, A.N., Ford Hendry

Lewis, Thos. C., Wilmington

Loudermilk, Z.H., Randolph County

Lyon, R.H., Black Rock

McDonald, J.R., Fayetteville

McIntosh, Frank, Richmond County

McLeod, Murdock, Carthage

McMillan, J.J., Wilmington

McRae, W.G., Wilmington

Mallet, C.P., Fayetteville

Malloy, J.D., Buck Horn

Moore, J.W., Wilmington

Mosely, N.S., Warrenton

Murphy, Wm. F., Clinton

Patrick, F.F., Columbia

Parham, S.J., Henderson

A few of the 600, including W.H. Kitchin, were confined in a felon’s cell at Hilton Head for the offense of

cutting the buttons off the coats of oath-takers, who, [Northern] Gen. [J.G.] Foster wrote to Gen. [Henry] Halleck,

were “the most worthless and unreliable fellows in the whole lot.”

(The South’s Burden, The Curse of Sectionalism in the United States, B.F. Grady, Nash Bros., 1906, pp. 144-147)

Copyright 2011, The North Carolina WBTS Sesquicentennial Commission