North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

Sherman and Total War

Colonel Charles Colcock Jones, who opposed Sherman under Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee,

summed up the feelings of many Southerners when he wrote:

"The conduct of Sherman's army and particularly of Kilpatrick's cavalry and the numerous parties

swarming through the country in advance and on the flanks of the main columns during the march

from Atlanta to the coast, is reprehensible in the extreme ... the Federals on every hand

and at all points indulged in unwanton pillage, wasting and destroying what could not be used.

Defenseless women and children and weak old men were not infrequently driven from

their homes, their dwellings fired, and these noncombatants subjected to insult and privation.

The inhabitants, white and black, were often robbed of their personal effects,

were intimidated by threats — and occasionally were even hanged to the verge of

strangulation to compel revelation of the places where money, plate and jewelry

were buried, or plantation animals concealed, — horses, mules, cattle and

hogs were either driven off, or were shot in the fields,

or uselessly butchered in the pens."

Faithfully Executing Northern War Policy

In North America, European influence had always dominated and this logically

included modes of warfare mostly in accordance with European standards. There were

of course departures from this but usually armies fought each other rather than

terrorizing civilian populations – the war with Mexico being an example which did

not revert to total war against noncombatants.

In his book “Advance to Barbarism, F.J.P. Veale writes: “. . . the first historic break with

European practice . . . took place in the sanguinary American Civil War (or “The War Between the States,”

as the Southerners still prefer to designate it). It was the Northern or Federal armies which produced

this historic reversion to primary or total warfare. The North had endured much more bellicose

contact with the Red Indians and was much less influenced by Europe than the South.”

(C.C. Nelson, 1953, pg. 121)

Veale finds “the traditional habit of saddling [Sherman with the] Northern departure from

civilized warfare” unjust. He saw that “Sherman only executed the most dramatic and

devastating example of the strategy which was laid down by President Lincoln himself and

was followed by General Ulysses S. Grant as commander-in-chief of the Northern armies.

Veale continues: “That Lincoln determined the basic lines of Northern military strategy has been

well-established . . . [and] Grant only efficiently applied Lincoln’s military policy in the field.

[Professor Harry T. Williams writes that Grant] “grasped the . . . concept that war was becoming

total and that the destruction of the enemy’s economic resources was as effective and legitimate

a form of warfare as the destruction of his armies.”

Hence it is apparent that Sherman was only carrying out effectively the military policy

which Lincoln and Grant had adopted (pg. 122).

Setting Precedent:

“[The] kind of warfare practiced by the Federal military during 1861-65 turned America –

and arguably the whole world – back to a darker age. “It scarcely needs pointing out,” wrote

Richard M. Weaver, “that from the military policies of [William T.] Sherman and [Philip] Sheridan

there lies but an easy step to the total war of the Nazis, the greatest affront

to Western civilization since its founding.”

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Walter Brian Cisco, Pelican, 2007, pg. 17)

Advent of a Systematic Warfare of Destruction

“The American Civil War . . . marked a decisive turn in the direction of total war.

This can be seen in a striking way because in that war both concepts were present:

the old chivalric concept of the war of limited objectives conducted against soldiers only

and the new one of unlimited warfare involving campaigns against civilians and the

total destruction of the resources of the enemy.

The Federal commander George B. McClellan and the Confederate General Robert E. Lee

belonged to the old school. Both conducted the type of war which is designed to overthrow

the opposing army and decide the issue on the field of battle. Clifford Dowdey speaks

accurately when he writes of McClellan:

“He did not consider it his duty, and it was certainly not his desire, to make war upon those

civilians among his countrymen who differed from him on the interpretation of the Constitution.

He fought without hate, without cruelty . . . [and not against] an alien people to conquer and despoil.”

It was possibly for this reason that Lincoln, and especially the Radical leaders of Congress,

became impatient with his “slowness,” which was the price of his respect for forms, and

removed him from command after the Battle of [Sharpsburg]. The character of the war

changed drastically, and in the last two years of the war [Sherman and Sheridan] carried

on a systematic warfare of destruction in Virginia, Georgia and the Carolinas with

the object of involving the entire population.

(Visions of Order, Richard M. Weaver, LSU Press, 1964, pp. 96-97)

Sherman wrote Lincoln in 1863:

“I would banish all minor questions, assert the broad doctrine that a nation has the right,

and also the physical power to penetrate into every part of our national domain, and that we

will do it -- that we will remove and destroy every obstacle, if need be, take every life,

every acre of land . . . that we will not cease till the end is attained . . . the South has

done her worst and now is the time for us to pile on blows thick and fast.”

(The South, A Documentary History, Ina W. Van Noppen, Van Nostrand, 1958, page 311)

“Orders Not Designed to Meet the Humanities of the Case”

[Atlanta], which had been formally surrendered [to Sherman] by the Mayor on September 2,

with the promise, as reported, on the part of the Federal commander,

that noncombatants and private property should be respected.

Shortly after his arrival, the commanding general of the Federal forces, forgetful of this

promise . . . issued an order directing all civilians living in Atlanta, male and female,

to leave the city within five days from the date of the order (September 5).

Since Alva’s atrocious cruelties to the noncombatant population of the Low Countries

in the sixteenth century, the history of war records no instance of such barbarous

cruelty as that which this order designed to perpetrate.

It involved the immediate expulsion from their homes and only means of subsistence

of thousands of unoffending women and children, whose husbands and fathers were either

in the army, in Northern prisons, or had died in battle.

In vain did the mayor and corporate authorities of Atlanta appeal to Sherman to revoke

or modify this inhuman order, representing in piteous language “the woe, the horror,

and the suffering, not to be described by words,” which its execution would inflict on

helpless women and children. His only reply was:

“I give full credit to your statements of the distress that will be occasioned by it, and yet shall not

revoke my order, because my orders are not designed to meet the humanities of the case.”

(Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Vol. II, Jefferson Davis, D. Appleton & Company, 1881, pp. 563-564)

Genersl Robert E. Lee’s Invasion

“In the midst of his 1863 invasion of the United States, Gen. Robert E. Lee issued a

proclamation to his men. After suffering for two years innumerable depredations

by their enemies, some Southerners, soldiers and civilians, thought at last the time

had come for retaliation. Lee would have none of that. He reminded his troops that

“the duties exacted of us by civilization and Christianity are not less obligatory in the

country of the enemy than in our own.”

“The commanding general considers that no greater disgrace could befall the army,

and through it our whole people, than the perpetration of barbarous outrages upon the

unarmed and defenseless and the wanton destruction of private property, that have marked

the course of the enemy in our own country . . . It must be remembered

that we make war only upon armed men . . . “

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Walter Brian Cisco, Pelican, 2007, pg. 15)

A Genocidal Nature

“Fort Sumter was fired upon, and now the sulking Achilles came out to fight; and with

him blood and iron would play a part from the very beginning. In May [1861] he declared:

“the greatest difficulty in the problem now before the country is not to conquer, but so

conquer to impress upon the real men of the South a respect for their conquerors.”

As the war got under way Sherman became hypnotized by it . . . and refused to be diverted by

those who would minimize the task or mollify it by soft considerations of the claims

of humanity or too close adherence to the rule book.

As condemnation of his prodigality in the use of men began to come in, he replied

that the war could not be fought with breath, but that hundreds of thousands of lives

must perish, and he added, “Indeed do I wish I had been killed long since.” [He] began

“to regard the death and mangling of a couple thousand men as a small affair, a kind of

morning dash – and it may be well that we become so hardened.”

[In 1862 he wrote] the Secretary of the Treasury, “The Government of the United States

may now safely proceed on the proper rule that all the South are enemies of all in the North.”

As to the large number of people who were being arrested [for disloyalty] in Kentucky,

he would send them “to the Dry Tortugas, or Brazil, every one of those men, women

and children, and encourage a new breed.”

“To secure the navigation of the Mississippi River [to Northern shipping] I would slay millions.

On that point I am not only insane, but mad.” For every shot fired at a [Northern] river

steamer he would return “a thousand 30-pound Parrotts into every helpless town on Red,

Ouchita, Yazoo, or wherever a boat can float or a soldier march.”

But for no reason beyond the fact that the South was opposing the North, he would set stark

starvation loose upon the land. Before beginning his Meridian campaign early in 1864,

he wrote his wife, “We will take all provisions, and God help the starving families.”

[In 1863 he insisted] on war, pure and simple, with no admixture of civil compromises . . .

[and] considered it unwise at that time “or for years to come” to give the southern people

“any civil government in which the local people have much to say . . . All the Southern States

will need a pure military Government for years after resistance has ceased.”

By the summer of 1864 . . . [Sherman] offered this advice to General Sheridan, who might

find it useful in the Shenandoah Valley: “I am satisfied, and have been all the time, that the

problem of this war consists in the awful fact that the present class of men who rule the South

must be killed outright rather than in the conquest of territory . . . Therefore I shall expect you

on any and all occasions to make bloody results.”

He wrote Grant his well-known article of faith, “Unless we can repopulate Georgia it is useless

to occupy it; but the utter destruction of roads, houses and people will cripple their military

resources . . . After he had reached Savannah he wrote to Halleck, “ We are not only fighting

hostile armies, but a hostile people, and we must make old and young, rich and poor,

feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies.”

When he found himself on one of Howell Cobb’s plantations in Georgia, he instructed

his army “to spare nothing,” and on the march through South Carolina, one chilly night

he consumed in the blazing fireplace the furniture of “one of those splendid South Carolina

estates where the proprietors had formerly dispensed hospitality that

distinguished the regime of that proud State.”

His first disagreement with the Radical reconstructionists grew out of his long-standing

attitude toward the Negro. He had spurned abolitionism in 1861, and during the war he had

shown his contempt for Negro soldiers. He wrote in May, 1865, “. . . I do not favor the

scheme of declaring the Negroes of the South, now free, to be loyal voters, whereby

politicians may manufacture just so much more pliable electioneering material . . .

they are no friends of the Negro who seek to complicate him with new prejudices.”

Sherman set down as an article of faith, “The white men of this country will control it,

and the negro, in mass, will occupy the subordinate place as a race.”

[His postwar belief regarding Radical Reconstruction is summed up with] “The South is ruined

and appeals to our pity. To ride the people down with persecutions and military exactions would

be like slashing away at the crew of a sinking ship.”

(Sherman and the South, Coulter, North Carolina Historical Review, 1931, excerpts, pp. 46-53)

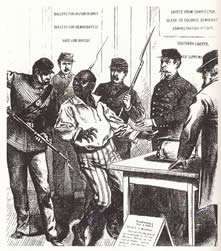

Sherman's View of the Black Race

“I won’t trust niggers to fight, wrote William T. Sherman in the spring of 1863,

“but don’t object to the Government taking them from the enemy, & making

such use of them as experience may suggest.”

In Union-occupied Tennessee the army impressed blacks and put them to work at hard

labor or hired them out to private contractors who often literally starved them. Many who

traded Southern owners and overseers for Yankee bosses,” observed an historian,

“very quickly discarded any lingering notions about Northern benevolence.” One Union

army officer in Nashville admitted that “colored men here are treated like brutes.”

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Walter Brian Cisco, Pelican, 2007, pp. 174-175)

Lecturing a Subordinate on Genocide

Headquarters, Department of Tennessee, January 1, 1863, Major R. M. Sawyer, AAG Army of Tennessee, Huntsville:

"Dear Sawyer---In my former letter I have answered all your questions save one, and that

relates to the treatment of inhabitants known, or suspected to be, hostile or "secesh." The war

which prevails in our land is essentially a war of races. The Southern people entered into a

clear compact of government, but still maintained a species

of separate interests, history and prejudices.

These latter became stronger and stronger, till they have led to war, which has

developed the fruits of the bitterest kind. We of the North are, beyond all question, right in

our lawful cause, but we are not bound to ignore the fact that the people of the South have

prejudices that form part of their nature, and which they cannot throw off without an effort of

reason or the slower process of natural change. Now, the question arises, should we treat

as absolute enemies all in the South who differ with us in opinions or prejudices – [and] kill

or banish them? Or should we give them time to think and gradually change their conduct so

as to conform to the new order of things which is slowly and gradually creeping into their country?

When men take arms to resist our rightful authority, we are compelled to use force

because all reason and argument ceases when arms are resorted to.

If the people, or any of them, keep up a correspondence with parties in hostility,

they are spies, and can be punished with death or minor punishment. These are

well-established principles of war, and the people of the South having appealed to war,

are barred from appealing to our Constitution, which they have practically and publicly defied.

They have appealed to war and must abide its rules and laws.

The United States, as a belligerent party claiming right in the soil as the ultimate sovereign,

have a right to change the population, and it may be and it, both politic and best, that we

should do so in certain districts. When the inhabitants persist too long in hostility, it may

be both politic and right that we should banish them and appropriate their lands to a more

loyal and useful population. No man would deny that the United States would be benefited

by dispossessing a single prejudiced, hard-headed and disloyal planter and substitute in

his place a dozen or more patient, industrious, good families, even if they be of foreign birth.

It is all idle nonsense for these Southern planters to say that they made the South,

that they own it, and that they can do as they please -- even to break up our government,

and to shut up the natural avenues of trade, intercourse and commerce.

We know, and they know if they are intelligent beings, that, as compared with the whole

world they are but as five millions are to one thousand millions -- that they did not create

the land -- that their only title to its use and enjoyment is the deed of the United States,

and if they appeal to war they hold their all by a very insecure tenure. For my part, I believe

that this war is the result of false political doctrine, for which we are all as a people responsible,

viz: That any and every people has a right to self-government . . . In this belief, while

I assert for our Government the highest military prerogatives, I am willing to bear in patience

that political nonsense of . . . State Rights, freedom of conscience, freedom of press,

and other such trash as have deluded the Southern people into war, anarchy, bloodshed,

and the foulest crimes that have disgraced any time or any people.

I would advise the commanding officers at Huntsville and such other towns as are

occupied by our troops, to assemble the inhabitants and explain to them these plain,

self-evident propositions, and tell them that it is for them now to say whether they

and their children shall inherit their share. The Government of the United States has

in north Alabama any and all rights which they choose to enforce in war -- to take their

lives, their homes, their lands, their everything . . . and war is simply power

unrestrained by constitution or compact.

If they want eternal warfare, well and good; we will accept the issue and dispossess them,

and put our friends in possession. Many, many people, with less pertinacity than the

South, have been wiped out of national existence.

To those who submit to the rightful law and authority, all gentleness and forbearance;

but to the petulant and persistent secessionists, why, death is mercy, and the quicker

he or she is disposed of the better. Satan and the rebellious saints of heaven were allowed

a continuance of existence in hell merely to swell their just punishment."

W.T. Sherman, Major General Commanding

(Reminiscences of Public Men in Alabama, Garrett, 1872, pp. 486-488)

The Search for Loot

“While we were gone – as I anticipated – nine . . . bummers quietly surrounded the dwelling . . .

and entered the grounds from different directions. The [owner] was sitting in a chair on the

front gallery by the door, and the first intimation he had that the thieves were at work was a

hand from behind him passed, snakelike, over his shoulder and down to his vest pocket to

get his watch; fortunately he had placed it where it was safe. In a few minutes those in the

house went through every wardrobe, bureau, closet, etc.

They took all the silverware and jewelry.

When the Yankees went to my plantation, in five minutes a company of about thirty

men marched into the garden, formed line, fixed bayonets, and, marched abreast,

probed the ground until they struck a box that was buried there containing silver

tableware. But in this case I am sure “old Aaron,’ a house servant who buried it

there for mother, betrayed her confidence and told the Yanks where it was.”

(Two Wars, Autobiography of Gen. Samuel G. French, Confederate Veteran, 1901, pp. 308-309)

Sherman Approaches Atlanta, 1864

David P. Conyngham was born in Ireland in 1840 and emigrated to New York at an early age.

At age 24 he accompanied Sherman’s army through the Georgia and Carolina campaigns.

His observations appeared in book form as “Sherman’s March Through The South,” (1865).

Though his sympathy was with the Union army he accompanied, he developed an infinite

compassion for the helpless souls caught in the struggle.

“Women and children were dreadfully frightened at the approach of our army.

It was almost painful to witness the horror and fear depicted on their features.

The country trembled at our approach, and hid themselves away in woods and caves.

I rode out one evening alone to pay a visit to another camp, which lay some six miles beyond us.

In riding along…I thought I saw a woman among the trees. Fearing a snare, I followed pistol

in hand; and heavens, what a sight met my view! In the midst of a thicket sheltered by a

bold bluff, were a dozen women, as many children and three old men almost crazy with fear

and excitement. Some of them screamed when they saw me,

and all huddled closer as if resolved to die together.

I do not think that one could realize so much wretchedness and suffering as that group presented.

Some of the women were evidently planters’ wives and daughters; their appearance and worn

dresses betokened it; others were their servants or the wives of the farm-laborers. There were

two black women and some three picaninnies. Under the shelter of a tree I saw a woman sitting

down, rocking her body to and fro, as she wept bitterly. I went over to her. Beside her was

a girl of some fourteen years, lying at full length.

She was dead. I understood she was delicate; and the hunger and cold had killed her.

So much were they afraid of being discovered that they had not even a fire lighted.”

Sherman’s “March to the Sea”

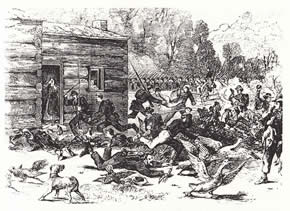

[In Madison, Georgia], the stragglers, who managed to get to the front when there

is plunder in view , and vagabonds of the army, crowded into the town and the work of pillage

went on with a vengeance. Stores were ripped open; goods, valuables and plate,

all suddenly and mysteriously disappeared.

Grinning Negroes piloted the army, and appeared to be in their element. They called out,

“Here massa, I guess we gwine to get some brandy here.” The doors would at once be

forced open, the cellars and shelves emptied, and everything tossed about in the utmost

confusion. If a good store chanced to be struck, the rush for it was immense.

I have seen fellows carry off a richly gilted mirror, and when they got tired of it, dashed it to

the ground. A piano was a much-prized article of capture. I have also witnessed the ludicrous

sight of a lot of bearded, rough soldiers capering about the room in a rude waltz . . . when they

got tired of this saturnalia, the piano was consigned to the flames, and most likely the

house with it. Cellars of rich wine were discovered, and prostrate men gave evidence of its

strength, without any revenue test. A milliner’s establishment was sacked, and gaudy ribbons

and artificial flowers decorated the caps of the pretty fellows that had done it.

We reveled in the splendid homes and palatial residences of some of the wealthy planters here.

The men…made themselves as much at home in the fine house of the planter as in the shanty

of the poor white trash or the Negro. They helped themselves, freely and liberally,

to everything they wanted, or did not want. It mattered little which.

Our campaign though central Georgia was one delightful picnic. We had little or no fighting,

and good living. A planter’s house was overrun in a jiffy; boxes, drawers, and escritoires

were ransacked with a laudable zeal, and emptied of their contents. If the spoils were ample,

the depredators were satisfied, and went off in peace; of not, everything was torn and destroyed,

and most likely the owner was tickled with sharp bayonets into a

confession of where he had his treasures hid.

Hogs are bayoneted, and then hung in quarters on the bayonets to bleed; chickens,

geese and turkeys are knocked over and hung in garlands from the saddles and around

the necks of swarthy Negroes…cows and calves…if too weak to travel are shot.

Should the house be deserted, the furniture is smashed to pieces, music is pounded out

of $400 pianos with the end of muskets. After all was cleared out, most likely some set

of stragglers wanted to enjoy a good fire and set the house, debris of furniture and all the

surroundings in a blaze. This is the way Sherman’s army lived on the country.

If a house was empty, this was prima facie evidence that the owners were rebels and all was

sure to be consigned to the flames. If they remained at home, it was taken for granted that

everyone in South Carolina was a rebel, and the chances were, the place was consumed…

and the country was converted into one vast bonfire. The pine forests were fired, the resin

factories were fired, the public buildings and private dwellings were fired.

Vandalism of this kind…was seldom punished. True, where everyone is guilty there will be no informers . . .

The only cases I know of theft being punished was on one or two occasions.

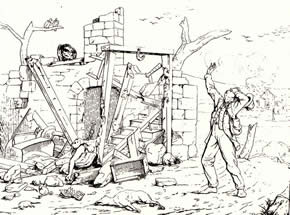

The word “bummer” has so often occurred in this work, that I think it well to give

an account of the signification of the name. Fancy a raged man, blackened by

the smoke of many a pine-knot fire mounted on a scraggy mule, without a saddle,

with a gun, a knapsack, a butcher knife, and a plug hat, stealing his way through

the pine forests far out on the flanks of a column, keen on the scent of rebels,

or bacon, or silver spoons, or corn, or anything valuable, and you have him in your mind.

Think how you would admire him if you were a lone woman, with a family of

small children far from help, when he blandly inquired where you kept your valuables.

Think how you would smile when he pried open your chests with his bayonet,

or knocked to pieces your tables, piano and chairs, tore your bedding into

three-inch strips, and scattered them about the yard.

The bummers say it takes too much time to use keys. They go through a Negro cabin in

search of diamonds and gold watches with just as much freedom and vivacity

as they “loot” the dwelling of a wealthy planter.

Terrorizing South Carolina

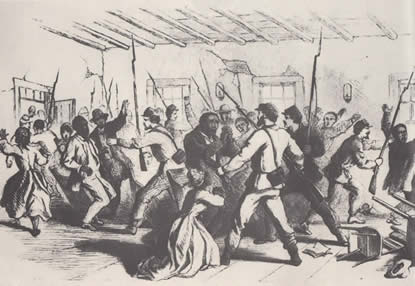

[In Columbia, South Carolina], crowds of our escaped prisoners, soldiers and Negroes,

intoxicated with their new-born liberty, which they looked upon as a license to do as

they pleased, were parading the streets in groups. As soon as night set in there ensued

a sad scene indeed. The suburbs were first set on fire . . . Pillaging gangs soon fired

the heart of the town, then entered the houses, in many instances carrying off articles

of value. The flame soon burst out in all parts of the city, and the streets were quickly

crowded with helpless women and children, some in their nightclothes. Invalids had to

be dragged from their beds and lay exposed to the flames and smoke that swept the

streets, or to the cold of the open air in back yards.

I trust I shall never witness such a scene again -- drunken soldiers rushing from house to house,

emptying them of their valuables and then firing them; Negroes carrying off piles of booty

and grinning at the good chance, and exulting, like so many demons; officers and men

reveling on the wines and liquors, until the burning houses buried them in their drunken

orgies. I was fired at for trying to save an unfortunate man from being murdered.

The frequent shots on every side told that some victim had fallen. Shrieks, groans, and cries of

distress resounded on every side. Men, women and children, some half naked as they rushed

from their beds were running frantically about, seeking their friends or trying to escape from

the fated town. A troop of cavalry, I think the 29th Missouri, were left to patrol the streets; but I did

not once see them interfering with groups that rushed about to fire and pillage the houses.

The 18th of February dawned upon a city of ruins. All the business portions, the main streets,

the old capitol, two churches and several public buildings were one pile of rubbish and bricks.

The streets were full of rubbish, broken furniture, and groups of crouching, desponding, weeping,

helpless women and children. Children were crying with fright and hunger; mothers were

weeping; strong men, who could not either them or themselves sat bowed down,

with their heads buried in their hands.”

(A Mirror For Americans, Volume II, William S. Tryon, editor, 1952, pp. 415-441)

Sherman’s Assessment of the Negro

“General Sherman said, “We all felt sympathy for the negroes, but of a different kind from

that of Mr. Stanton, which was not of pure humanity, but of politics . . . I did not dream

that the former slaves, without preparation, would be manufactured into voters . . .

I doubted the wisdom of at once clothing them with the elective franchise . . .

and realized the national loss in the death of Mr. Lincoln, who had long

pondered over the difficult questions involved.”

(“Dixie After the War”, M.L. Avary, pp. 281-282)

Drowning in Ebeneezer Creek

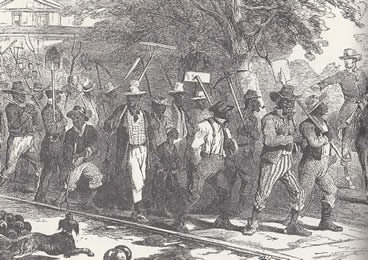

“[Sherman’s army] was now nearing the [Georgia] coast . . . [and] continued to support its

burden of Negro followers . . .altogether about twenty-five thousand – four Negroes for every

ten soldiers – tagged along, but about three-fourths of them became disillusioned by their

new “freedom” and, a few days after starting out, began the weary trek back to their home

places. When Sherman and his men came within sight of the coast,

the horde had dwindled to sixty-eight hundred.

In camp they looked after the pots and pans and helped out with the cooking. At night they

entertained their “liberators” with their plaintive plantation melodies.

And the good-looking women peddled sex.

Sherman naturally was reluctant to take on these added appetites to be satisfied.

And he had a strong personal dislike for colored people. (“Damn the nigger!” he once

exploded.) Women with young children [were] puffing and panting to keep up with the procession . . .

Some [babies] fell off [the back of mules] while the caravan

was crossing swamps and were drowned.

A large number of Negroes lost their lives in a few minutes of horror at Ebeneezer Creek.

[One of Sherman’s subordinates pulled up the pontoon bridge after the army crossed],

leaving the Negroes on the west bank. In desperation the Negroes attempted a mass crossing.

Even the few who could swim had great trouble making it . . . [but] many were drowned.”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, John M. Gibson, 1961, pp. 73-74)

Vandalizing Georgia:

“The much-vaunted “march to the sea” was a pleasure excursion, through a well-cultivated country . . .

Sherman boastfully writes that he “destroyed two hundred sixty-five miles of railroad, carried

off ten thousand mules, and countless slaves; that he did damage to the amount of $100,000,000.

Of this, his army got $20,000,000, and the $80,000,000 was waste,”

as they went “looting” through Georgia.

But not content with this, when “this cruel war was over,” he presented the delectable

spectacle of “how we went thieving through Georgia” at the grand review of his army in

Washington, by mounting his bummers on mules laden with chickens, ducks, geese,

lambs, pigs and other farm productions, unblushingly displayed, to cover up the concealed

money, jewelry and plate taken from the helpless women – to delight the President, to edify

the loyal people, to gratify the hatred of the populace to the South, to popularize the thirst for

plundering made by his troops, to be an object lesson to the present generation, to instill

a broader view of moral right, to heighten modest sensibilities, to refine the delicate

tastes of young ladies, to humiliate a conquered people; or wherefore

was this unwise “Punch and Judy” show given?

During the revolutionary war, when the British fleet ascended the Potomac river, one ship

sailed up to Mount Vernon – the residence of the arch rebel, Washington – and made

a requisition for provisions which his agent filled. The English commander must have

been a gentleman because he did not burn the dwelling,

insult the family, nor commit robbery!!!

Gen. Bradley T. Johnston, in his life of General J.E. Johnston, quotes that,

“Abubekr in the year 634 gave his chiefs of the army of Syria orders as follows:

“Remember that you are always in the presence of God, on the verge of death,

and in the assurance of judgment and the hope of paradise. When you fight the

battles of the Lord acquit yourselves like men, without turning your backs;

but let not your victory be stained with the blood of women and children.

Destroy no palm tree, nor burn any fields of corn….

nor do any mischief to cattle,

only such as you kill to eat . . .”

It is not I who charge Sherman with destroying cornfields, cutting down fruit trees,

or “driving off one cow and one pig;” he himself boasts as having done it. If he did take

“one cow and one pig,” he kindly left the poor women their tears and their memory.”

(Two Wars, French, 1901, pp. 264-266)

Vandalizing South Carolina

“Through the month of January (1864), a large part of Sherman's army passed through

Beaufort on the way to resume its march through the mainland of South Carolina.

The abuse of the freedmen that had always occurred whenever new troops came

into the island district was vigorously reenacted. Some soldiers cheated the Negroes

by selling them horses they did not own, and others behaved "like barbarians, shooting

pigs, chickens and destroying other property."

Negroes who attempted to defend their belongings were "very roughly" handled. Most of the

men spoke scornfully of "niggers" and would not listen to (Northern) teachers who

stoutly maintained that their scholars had ability equal to whites. General Saxton was

at last obliged to place Beaufort out of bounds to freedmen, for their own protection.

The missionaries and the spit and polish Eastern regiments stationed at Port Royal were

looking at an army the like of which they had never seen before. While ferociously

disparaging "niggers," the Westerners were inconceivably democratic among themselves.

"The officers and men are on terms of perfect social equality," marveled Arthur Sumner.

"Off duty they drink together, go arm in arm about the town, (and) call each other by

the first name in a way that startles the Eastern man. One civilian agent gasped to

hear a private address a brigadier general as "Jake."

The brotherhood of the Western army stopped abruptly, however, at the color line.

The Western soldier was appalled by the free manners of the missionaries with the Negroes.

The sight of "a beautiful white woman driving in a wagon with a coal-black Negro man "

so shocked one soldier that he subsequently declared he would have shot her on the spot,

"if she had been anything to me." "Sherman and his men," explained Arthur Sumner to

a Northern friend, "are impatient of darkies, and annoyed to see them so pampered,

petted and spoiled, as they have been here."

[While in Beaufort], Sherman's men made free use of all property "lying around loose"

and burned great quantities of lumber to keep the "movable army" warm. The morale

of the Western troops was high because they had made the slaveholding aristocrats

of Georgia feel the force of their élan. They could hardly wait to get to South Carolina.

The goal of Negro emancipation would continue to play for the "ragged heroes" a poor

second to the preservation of the Union and the destruction of treason.

In the matter of recruiting [black soldiers], General Saxton had assured [them] that

no man would be taken against his will, but he had been undone by General Hunter

in the first place, by General Quincy Gilmore in the second place, and last by General

John G. Foster, who in 1864 resumed wholesale recruiting "of every able-bodied male

in the department."

The atrocious impressment of boys of fourteen and responsible

men with large dependent families, and the shooting down of Negroes who resisted, were

all common occurrences. The Negroes who had been enlisted were promised the same

pay as other soldiers. They had received it for a time, "but at length it was reduced,

and they received but little more than half of what was promised."

(Rehearsal for Reconstruction, The Port Royal Experiment, Willie L. Rose, Vintage Books, 1964)

“When Sherman’s troops came through in 1864 everything was stolen or destroyed,

whether owned by planters or by hard-working slaves. A white diarist recorded that black women

were particularly threatened by the invaders. “These men were so outrageous at the Negro houses

that the Negro men were obliged to slap at the [soldiers’] horses (causing them to bolt) for the

protection of their wives, and in some instances they rescued them from the hands of these

infamous creatures.” One historian concluded that . . . “indiscriminate confiscation of black

property, and other anti-Negro acts committed by Sherman’s army, had a corrosive effect on

the enthusiasm with which many had welcomed them.”

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Cisco, 2007, pg. 175)

A seething hatred of South Carolinians consumed Sherman – they – men, women

and children -- were to be taught a stern lesson of terror and destruction for daring to

resort to arms to defend their rights under the Constitution from usurpation.

He would turn a blind eye at Columbia.

The Sack of Columbia

“Shortly after nightfall [on 17 February 1865] . . . A minister, standing in his front yard when

the first [signal] rocket went up, heard Federal soldiers [nearby] remark: “Now you will catch

hell – that is the signal for a general setting of fire to the city.” There can be little doubt that

the capital city of South Carolina was deliberately fired by the soldiers in blue . . .

“in more than a hundred places.”

Prepared for the job at hand, emboldened by whiskey, and ever increasing in members,

“the drunken devils roamed about setting fire to every house in every direction . . . “ The local

citizens gave up all thought of sleep and watched by the red glare of burning buildings the

“wretches” in blue as they walked the streets singing, hurrahing, cursing South Carolina,

swearing, blaspheming, and singing ribald songs.

Heart-rending cries of those in distress, the terrified lowing of cattle, and the frenzied

flights of pigeons added to the pathos of the situation. The college library next to the LeConte home

“seemed framed by the gushing of flames and smoke, while through the windows gleamed the

liquid fire . . . “The other buildings on the campus, filled with three hundred sick

and wounded soldiers, were soon on fire.

Three times the Methodist Church was set on fire. The pastor, the Reverend Mr. Connor,

twice put out the flames, but when the parsonage next door was fired, he had to tend his

sick child whom he carried out of the house in his arms. So incensed was one soldier

by this time that he tore off the child’s blanket and threw it into the flames, saying:

“Damn you, if you say a word I’ll throw the child after it.”

The Ursuline Convent suffered the same fate as the Methodist Church . . .

During the night, as the soldiers milled around the convent and sparks began to fall on

the buildings, the Mother Superior decided to evacuate the premises. Consequently . . .

[drunken soldiers] began to ransack the school. A thorough job of pillage was

enacted before flames destroyed the building.

Soldiers fired the house of [Dr. Robert Wilson Gibbes] by piling furniture in the drawing room

and igniting it . . . Lost in the blaze was a large library, many portfolios of fine engravings,

more than a hundred paintings, “a remarkable cabinet of Southern fossils,” one of the finest

collections of shark’s teeth in the world, American and Mexican relics, and an extensive

collection of historical documents, including much original

correspondence on the [American] Revolution.”

Drunks staggered under the accumulation of [stolen] sterling trays, vases, candelabra,

cups and goblets. Clothes and shoes, when new were usually appropriated, the rest

left to burn. Fraternal Orders were not overlooked [with drunken soldiers] absurdly

attired in Masonic and Odd Fellow regalias [strolling] about the streets.

The Negroes, urged by the ruffians to get in on the fun, were told they were receiving their

wages for years of unpaid labor. A fair number, having been disillusioned by the conduct

of their “friends” from the North, remained loyal to their masters.

There were very few rapes [reported] against the white women of Columbia . . .

[though] an extreme practice [was to ] catch her by the throat and feel in her bosom

for a watch or pull up her dress in search of a purse hidden in her girdle or petticoat.

Negro women were for the most part victims of the soldiers’ lust. A number of them

were woefully mistreated and ravished . . . [and many who fled their huts at night] fell

victim to the soldiers’ desires. The next morning their unclothed bodies, bearing the

marks of detestable sex crimes, were found about the city. An old Negro woman

belonging to the Reverend Mr. Shand was subjected to several brutal assaults . . .

[and] “put into the ditch and her head held under the water until her life was extinct.”

With the first light of dawn . . . The greater part of Columbia was in ashes. From the center

of town as far as the eye could reach, nothing was to be seen “but heaps of rubbish, tall dreary

chimneys, and shattered brick walls . . . “ The homeless, gathered in the open spaces and

parks of the city and huddled around their few belongings, were a pitiful sight . . . “crowded

with homeless women and children, a few wrapped in blankets and shivering in the night air.

Whitelaw Reed, the Ohio politician, called the burning of Columbia the “most monstrous

barbarity of the barbarous march.” On the night of the fire Sherman was inclined to

attribute the conflagration to whiskey. In conversation with Mayor Goodwyn that evening

he complained: “Who could command drunken soldiers?”

{Sherman later stated:] “Though I never ordered it and never wished it, I have never shed

any tears over the event, because I believe that it hastened what we all fought for,

the end of the war.” One native of Columbia expressed it: “They destroyed everything

which the most infernal Yankee ingenuity could devise means to destroy.’

(Sherman’s March Through the Carolinas, Barrett, 1956, excerpts, pp. 81-91)

“One black woman, a servant of Columbia minister Peter Shand, was raped by

seven soldiers of the United States Army. She then had her face forced down into a

shallow ditch and was held there until she drowned. William Gilmore Simms reported

how “regiments, in successive relays,” committed gang rape

in Columbia on scores of slave women.

“What does this mean boys” asked Sherman, coming upon a young African-American man

dead on a Columbia street. “The damned black rascal gave us his impudence,

and we shot him,” calmly replied a soldier.

“Well, bury him at once!” ordered Sherman.“Get him out of sight!”

When asked about the matter, Sherman said that “we have no time

for courts-martial and things of that sort!”

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Cisco, 2007, pp. 181-183)

Rapists in Blue

“Mary Chestnut recorded in her diary the horrific news that the bodies of eighteen black women

had been discovered on the Sumter District plantation of her niece Minnie Frierson and

husband James. Each had been stabbed in the chest with a bayonet.

“The Yankees were done with them! Wrote Mrs. Chestnut: “These are not rumors

but tales told me by the people who see it.”

(War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Cisco, 2007, pg. 183)

Vandalizing North Carolina

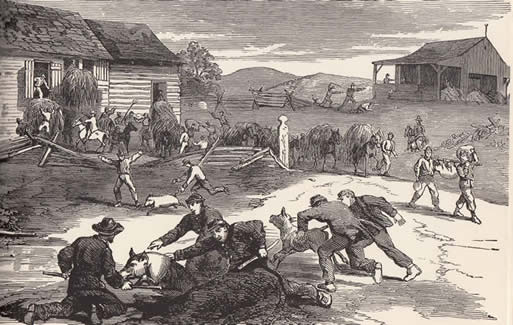

“The first sizeable raid [of Sherman’s cavalry in North Carolina] was at Monroe . . .

and Wadesboro . . . Striking furiously, a party . . . invaded and terrorized the town and

nearby rural community. The Rev. Thomas Atkinson, Episcopal Bishop of North Carolina,

gave up his watch, clothing, jewelry and horse under the threat of being killed if he refused.

A raider shot down one of the oldest and wealthiest residents of the county in his own house

when the old man did not surrender his money and watch, which he could not do because

another raider had already taken them.

Another wealthy Anson county resident stood by helplessly while the bluecoats fired his cotton gin,

and burned more than two hundred bales of cotton and destroyed his well-filled corn crib,

his granary, wheat, oats and field peas.

The raiders . . . broke into one place and “cut into fragments with an axe” every piece of furniture.

They “opened the [bed] tick and scattered the feathers over the floors of the chamber,” and

they filled buckets with molasses “and mixed it with the feathers by thoroughly stirring.”

Before they left the plantation . . . they hooked up the family’s team of bay horses [to their carriage]

and loaded it with hams from the smokehouse and other choice foods. Then they either shot or

drove off every horse, mule, cow, sheep, goat, duck and chicken around the place.”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, Gibson, 1961, pp. 189-190)

“House-burning, supposed to have ended at the State line, broke out again in the Antioch section.

Bluecoats were in the act of firing the home of Daniel S. Morrison when the Morrison children

saw them and started screaming. The soldiers took the hens off their nests, seized Mrs. Morrison’s

jewelry and talked the Morrison’s slaves into going off with them. The Negroes soon regretted

going, and returned home, sick and disillusioned. Mrs. Morrison nursed them back to health.”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, Gibson, 1961, pg. 196)

“Troops from Kilpatrick’s cavalry ransacked the Duncan Murchison mansion about

twelve miles from [Fayetteville] and, angered by their failure to find the carefully hidden

valuables, stormed into the bedroom of a young girl gravely ill with typhoid. When

relatives and neighbors pleaded with them to show some compassion for a dying child, an

officer told his men, “Go ahead, do all the mischief you can.”

She died while they were there.

Then they tried to kill seventy-year-old Mr. Murchison. While a friend of the old man

begged on her knees for his life, the soldiers dragged him half-dressed into the swamps

and left him. Inside the house they drove their swords into family portraits, broke up

furniture and poured molasses into the piano. The family was left without anything to eat.

They managed to stay alive by gathering up corn and other grain that

had been scattered about by horses.”

At another place the family Bible was spread open, thrown across a mule’s back, and used as a saddle”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, Gibson, 1961, pg. 204)

Black and White Suffering

“The Negroes suffered along with the white people. Martha Graham, a former slave,

told a newspaper writer . . . They took all the corn [out of] the crib and the things

[we had] stored. A soldier visited the house while her mother was straining milk.

Without saying a word, he picked up one of the two milk pans and drained it.

A few seconds later – “as soon as he hit the bottom step [after leaving], “ – she heard

a shot: “They [were] killing our turkey.”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, Gibson, 1961, pg. 204-205)

“[In April, 1865] seventeen-year-old Janie Smith . . . called “Sherman’s troops “fiends incarnate” . . .

[that] they left no living thing in Smithville – her home town and immediate site of the battle

[of Bentonville] – “but people and an old hen.” The Yankees “would run all over the yard to

catch the little things to squeeze to death.” They searched “every nook and corner,”

and the things they didn’t use were burned or torn to strings. They set the blacksmith

shop afire, and “into the flames they threw every tool plow, etc., that was on the place.”

They kicked down fences “like mad cattle” and marched into the house, “breaking open bureau

drawers of all kinds, faster than I could unlock” them. They “cursed us for having hid

everything and made bold threats if certain things were not brought to light . . .

all to no effect.” They “took Pa’s hat and struck him pretty badly with

a bayonet to make him disclose something . . .”

Everything of value she and her family had was lost . . . If she ever saw a ‘Yankeewoman,”

she intended to “whip her and take the clothes off of her back.” Looking forward optimistically

to an invasion of the North, she hoped Johnston’s and Lee’s armies would “carry the torch

in one hand and the sword in the other.” She wanted “desolation carried to the very heart of

their country . . . the widows and orphans left naked and starving just as ours were left.”

(Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, Gibson,1961, pp. 216-217)

The American South has not forgotten the misdeeds of a criminal military commander

sent by Abraham Lincoln to devastate their country, homes and lives – to this day Southerners

refuse to allow memorializing he and his vandals at any battlefields in their land.

War is Not Hell Unless a Devil Wages It:

“Petition to the Postmaster General by the Citizens of Texas:

We, the citizens of Huntsville, Tex., respectfully petition the Postmaster General to place

on sale in this State no stamps or postal cards bearing the likeness of W.T. Sherman.

We are loyal citizens, we love our country, we wish to forget the past differences and

bitterness; but there are two things which no true Southerner will ever forget or cease

to teach his children to remember. These are the deeds of W.T. Sherman

and the period of Reconstruction.

There were enough brave and chivalrous Union generals in the Civil War to

furnish subjects for stamps, and we object to the face of a ruffian who made war

on women and children being placed among the faces or Washington, Franklin,

Jefferson . . . and other honorable men and forced upon our children

when we have done nothing to deserve insult.

Sherman observed the laws of civilized warfare only when he had a hostile

army to fear. When Hood was defeated the people were helpless and defenseless,

he set his bummers upon them and boasted of it. Union armies were not bad unless

they had bad leaders. Among civilized people war is not hell unless a devil wages it.

If this man’s face is forced before us in this way, we shall be forced to teach in

public those lessons in history which we teach by the fireside, even if those with goods to

sell preach that all should be forgotten.

If W.T. Sherman’s face must be held up to view, send it to those who love his character

and celebrate his victory in song, but not to those whose homes he robbed, whose

daughters he insulted, whose sons he murdered, and whose cities and homes he burned.”

(Sherman’s Picture on U.S. Postage Stamps, Confederate Veteran, June, 1911, pg. 272)

To Humiliate a Conquered People

“But not content with [boastfully writing of his destruction on Georgia], when “this cruel war was over,”

he presented the delectable spectacle of “how we went thieving through Georgia” the grand review

of his army in Washington, mounting his bummers on mules laden with chickens, ducks,

geese, lambs, pigs and other farm productions, unblushingly displayed, to cover up the

concealed money, jewelry and plate taken from the helpless women – to delight the President,

to edify the loyal people, to gratify the hatred of the populace to the South, to popularize the

thirst for plundering made by his troops, to be an object lesson for the present generation,

to instill a broader view of moral right, to heighten modest sensibilities, to refine the

delicate tastes of young ladies, to humiliate a conquered people; or wherefore was

this unwise “Punch and Judy” show given?

Gen. Bradley T. Johnson, in his life of Gen. J.E. Johnston, quotes that “Abubekr gave

his chiefs of the army of Syria orders as follows: “Remember that you are always in the

presence of God, on the verge of death, in the assurance of judgment and the hope of paradise.

Avoid injustice and oppression . . . when you fight the battles of the Lord acquit yourselves

like men, without turning your backs; but let not your victory be stained with the blood

of women or children. Destroy no palm tree, nor burn any fields of corn.”

It is not I who charge Sherman with destroying cornfields, cutting down fruit trees, or

“driving off one cow and one pig;” he himself boasts of having done it. If he did take the

“one cow and the one pig,” he kindly left the poor women their tears and their memory.”

(Two Wars, Gen. Samuel G. French, Confederate Veteran, 1901, pp. 265-266)

Epilogue

Sherman and Lincoln, War Criminals:

“World War II was only one life span removed from the bloody hands of Sherman’s

Southern campaigns, even less than that from the warfare he levied on the Plains Indians.

At the close of World War II in 1945, the Allies commissioned and erected an international

tribunal to bring top Nazis to justice. The Charter of the International Military Tribunal,

known as the Nuremburg Trial Proceedings, has an eerie and familiar reverberation to it.

Title II, Article 6-13 of this charter establish the jurisdiction of the tribunal. Article 6

enables the tribunal to try and punish individuals’ crimes including:

(a) Crimes Against Peace: namely planning, preparation, initiation or waging a war of aggression . . . .

(b) War Crimes, namely . . . murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave labor or for any other

purpose of civilian population of the occupied territory . . . killing of hostages, plunder of public

or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns or villages, or devastation

not justified by military necessity;

(c) Crimes Against Humanity: namely, murder . . . deportation, and other inhuman

acts committed against any civilian population . . .

Clearly, Sherman and Lincoln were guilty on numerous counts of the crimes listed above.

As the political head of state, Lincoln’s guilt of “crimes against peace” and initiation

and waging a war of aggression cannot be controverted.

As the war dragged on, the Lincoln administration began to view military necessity

in a different light. The objective of the war was to reestablish political authority over

the Southern States. Gradually, any action that would likely hasten this was viewed

as militarily necessary.

Therefore, kidnapping, murder, torture, destruction of food stores

and livestock, and massive destruction of the means of food production [including

seizing slaves] came to be an acceptable consequence of restoring lost federal authority.

As Grant’s aide said, the Southern people, not just Southern armies, had to be “annihilated.”

[It] is important to expose the savagery of the U.S. Army toward the civilians of the South

because military commanders, political theorists, and despots worldwide watch and learn

from that which was tolerated in the past in order to apply it to future wars.

The federal government’s Civil War theory of military necessity and of total war,

originated by Americans to justify the butchering of other Americans, opened Pandora’s

proverbial box. Next time, the whole world would be involved. In World war II, the

justification for the haphazard destruction of London and massive fire destruction of

German and Japanese population centers were the twin evils military necessity and total war.”

(Lincoln Uber Alles, John Avery Emison, Pelican Publishing, 2009, pp. 250-253)

There was a time when certain groups, like women, children and the aged, were spared the

sufferings of war, and when armies fought each other on the field of battle to decide an issue.

This chivalric discrimination came to an end in the modern warfare practiced by Sherman.

Regressing Toward Total War

“The French Revolution marks the period when the impulse to end discrimination and to integrate

everything first began to make itself definitely felt. From the beginning of the age of chivalry until this

date the Western world had generally recognized a code of war.

The Napoleonic Wars following the French Revolution [brought] in the “democratic” conscript

army but they preserved the distinction between combatant and noncombatant. Civilians retained their

freedom of movement. The armies marched along paths prescribed for them, fought for victory rather

than for annihilation, and expected society to go on with its function. When the eighteen-year upheaval

was over, the central figure in it, though overthrown, was neither hanged or shot.

He was transported to an island where he could live out his years in comfort, if not in happiness.

When he escaped and repeated his offense, he was transported to a more remote island. There was

never any thought of trying to “prove” something by killing him. A distinction was preserved between an

enemy on the field of battle and an enemy captured.

During the Crimean War (1854-56) Russia continued to pay interest on its debt to its enemy Britain.

War was one thing; the honoring of financial obligations another.

The American Civil War, coming a decade later, marked a decisive turn in the direction of total war.

The Federal commander George B. McClellan and the Confederate General Robert E. Lee belonged

to the old school. Both conducted the type of war which is designed to overthrow the opposing army

and decide the issue on the field of battle. It was not part of their policy to turn the war against

civilians and non-military objectives.

[Lincoln and the Radical leaders of the Northern Congress] removed [McClellan] from command

after the battle of [Sharpsburg]. The character of the war thereafter was changed drastically, and in

the last two years the Federal Generals [Sherman and Sheridan] carried on a systematic warfare

of destruction in Virginia and the Carolinas with the object of involving the entire population.

The statement of the former that he would “bring every Southern woman to the washtub” and

the latter that he had devastated the Shenandoah Valley . . . sounded the end to the age of chivalry.

For his part in this General Sherman has been termed by an admiring biographer a “fighting prophet,”

who saw beyond the old concept of war to a new order, in which no one and nothing would be spared.

[The] advance toward totalism in [the First World War] certainly appears in the sweeping nature

of the conscription practiced by all belligerents and in the way in which every phase of life --

economic, financial, social, and cultural – was drawn into the struggle and made ancillary to

the war. To an unprecedented degree the idea was promoted that the nation should become

as one , with no thought but to kill and destroy.

The Second World War went immeasurably further and reduced the word “noncombatant” almost

to meaningless. Distinctions of sex and age and vocation vanished away. Neither status nor

location offered any immunity from destruction, and that often of a horrible kind. Mass killing

did indeed rob the cradle and the grave.

Our nation was treated to the spectacle of young boys fresh out of Kansas and Texas turning

nonmilitary Dresden into a holocaust which is said to have taken tens of thousands of lives,

pulverizing ancient shrines like monte Casino and Nuremburg, and bringing atomic

annihilation to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

These are items of the evidence that the war of unlimited objectives has swallowed up all

discrimination, comparison, humanity, and, we would have to add, enlightened self-interest.

We are compelled to recall Winston Churchill, a descendant of the Duke of Marlborough and in

many ways a fit spokesman for Britain’s nobility, saying that no extreme of violence

would be considered too great for victory.

Then there is the equally dismaying spectacle of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the reputedly great

liberal and humanitarian, smiling blandly and waving the cigarette holder while his agents

showered unimaginable destruction upon European and Japanese civilians.

The object of this reflection, however, is not to place blame for any particular atrocity, but to ask

whether civilization n has given itself a mortal hurt in going so far beyond bounds that were previously

respected. It is said that some kinds of animals become infected with a type of madness which

leads finally to their extinction as a species. Is this the kind of epitaph that will have to be written

for modern man if there is anyone left to write epitaphs?

(Visions of Order, The Cultural Crisis of Our Time, Richard M. Weaver, ISI Books, 1995, pp. 96-98)

Sources and Bibliography

(Rehearsal for Reconstruction, The Port Royal Experiment, Willie L. Rose, Vintage Books, 1964

Two Wars, The Autobiography & Diary of Gen. Samuel G. French, CSA, Confederate Veteran, 1901

Those 163 Days, A Southern Account of Sherman’s March, John M. Gibson, Bramhall House, 1961

A Mirror For Americans, Volume II, William S. Tryon, editor, University of Chicago Press, 1952

Reminiscences of Public Men in Alabama, William Garrett, Plantation Printing Company's Press, 1872

Sherman and the South, E. Merton Coulter, North Carolina Historical Review, Volume VIII, Number 1, January 1931

Lincoln Uber Alles, John Avery Emison, Pelican Publishing, 2009

War Crimes Against Southern Civilians, Walter Brian Cisco, Pelican, 2007

Sherman’s March Through the Carolinas, J. G. Barrett, UNC Press, 1956

Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Vol. II, Jefferson Davis, D. Appleton & Company, 1881

Visions of Order, The Cultural Crisis of Our Time, Richard M. Weaver, ISI Books, 1995

Copyright 2014, The North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission