North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission

Acts of Treason Against North Carolina

The question of loyalty to North Carolina is a seldom-discussed aspect of the War Between the States,

but an important topic nonetheless. Why did some North Carolinians choose to take the enemy’s side and

fight against their native State? Had North Carolina been victorious in the War Between the States, would it

have treated the “Buffaloes and renegades” as it did the Tories after the Revolution?

When the Northern fleet appeared off Hatteras in the fall of 1861, it was clear that the Lincoln administration

in Washington intended to invade North Carolina, and Lincoln's later appointment of former North Carolina resident

Edward Stanly as "governor" made it clear that the freely-elected government of North Carolina was to be overthrown

and replaced with one satisfactory to the North, not the people of North Carolina. Those levying war against North Carolina,

who adhered to and gave aid and comfort to the enemy, committed treason.

Definitions:

Traitor:

One who betrays his allegiance and betrays his country; one guilty of treason; one who, in breach

of trust, delivers his country to its enemy, or any fort or place entrusted to its defense, or who surrenders an army

or body of troops to the enemy, unless when vanquished; or who takes arms and levies war against his country;

or one who aids an enemy in conquering his country.”

(Webster’s Dictionary, 1828)

Treason:

“The action of betraying a trust; A violation by a subject of allegiance to the sovereign or to the State,

esp. by attempting or plotting to kill or overthrow the sovereign or overthrow the Government.”

(Oxford English Dictionary)

“Article 3, Section 3 of the U.S. Constitution defines treason as “only” levying war upon

the United States, or giving aid and comfort to their enemies. The “United States” is in the

plural, signifying free and independent States that are united in a cause. The word “their” is most

important because it also signifies that treason is defined only as levying war upon “them” – the free and

independent States, not something called “the United States government.”

This of course is precisely what Lincoln did when he levied war upon the Southern States.”

Dr. Thomas L. DiLorenzo, Loyola College

British and Colonial Origins of Treason Law

“The constitutional and legal foundation for the crime of treason was laid nearly 700 years ago

in the English statute of 25 Edward III (A.D. 1350).

{Among the] seven categories of “High Treason” in the Statute of Edward was that of “adhering”

to the King’s “enemies,” giving them “aid and comfort.” Although the provision endured throughout

the centuries in England, it is with the . . . colonial experience that its relevance [to America begins].

At one point or another, recognition of the crime of treason existed in most of the colonies, either

in express legislation or less formally. [The] first significant building block in the creation of the

modern American crime of treason came shortly after the Declaration of Independence. The Continental

Congress had formed the improbably named “Committee on Spies,” whose members included John Adams,

Thomas Jefferson, Robert Livingston, John Rutledge and James Wilson – all titans of the Revolution.

The Committee recommended that the colonies enact treason legislation, and Congress adopted the

recommendation, passed it on to the colonies, and, in doing so, utilized the then-familiar

language of the Statute of Edward:

“Resolved, That all persons abiding within any of the United Colonies, and deriving protection

from the laws of the same, owe allegiance to the said laws, and are members of such colony;

and that all persons passing through, visiting or make a temporary stay in any of the said colonies,

being entitled to the protection of the laws during the time of such passage, visitation,

or temporary stay, owe, during the same time, allegiance thereto:

That all persons, members of, or owing allegiance to any of the United Colonies, as before

described, who shall levy war against any of the said colonies within the same, or be adherent

to the King of Great Britain, or other enemies of the said colonies, or any of them, within the

same, giving to him or them, aid and comfort, are guilty of treason against such colony:

That it be recommended to the legislatures of the several United Colonies, to pass laws for punishing,

in such manner as to them shall seem fit, such persons before described, as shall be provably

attained of open deed, by people of their condition, of any of the treasons before described.”

Within a year, most of the former colonies, then members of the “United States,” had enacted

appropriate legislation using the Committee’s and the Congress’ recommended language.

Thus, at the birth of the Constitution of the United States of America in 1787, there was a

400-year-old acceptance of the idea that it was treason to “adhere” to a [Colony or State]

government’s “enemies” and give them “aid and comfort.”

(Aid and Comfort, Jane Fonda in Vietnam, Holzer & Holzer, McFarland & Company, 2002, pp. 95-96)

Buchanan Knew the Limits of Presidential Authority

“Mr. [James] Buchanan, the last President of the old school, would as soon have thought of aiding

the establishment of a monarchy among us as of accepting the doctrine of coercing the States into

submission to the will of a majority, in mass, of the people of the United States.

When discussing the question of withdrawing the troops from the port of Charleston, he yielded a ready

assent to the proposition that the cession of a site for a fort, for purposes of public defense, lapses,

whenever that fort should be employed by the grantee against the State by which the cession was made . . .

[and] the little garrison of Fort Sumter served only as a menace, for it was utterly incapable of holding

the fort if attacked . . . [and the attempt to provision it would be]

readily construed as a scheme to provoke hostilities.”

(Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, Vol. I, Jefferson Davis, 1881, pp. 216-217)

“[Dr. Marshall DeRosa notes . . . that Article III, Section 3, of the Constitution states:

“Treason against the United States shall consist of levying war against THEM or adhering

to THEIR enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.” [DeRosa explains:] “This is why Lincoln’s invasion

of the Southern States was the very definition of treasonous behavior under the Constitution.”

(The Long March Through the Constitution, C. Williamson, Jr., Chronicles, June 2014, pg. 27)

The North Carolina Constitution:

As noted elsewhere on this website, the State of North Carolina determined in convention assembled, to

peacefully withdraw from the political union it voluntarily joined in 1789, and then affiliate voluntarily with a new

political entity on 20 May 1861. It was no long part of the United States, and the allegiance of its citizens was

unquestionably to North Carolina. Facing immediate invasion from the North, and as the Constitution of 1776

did not address treason, an Amendment was added on 18 June 1861:

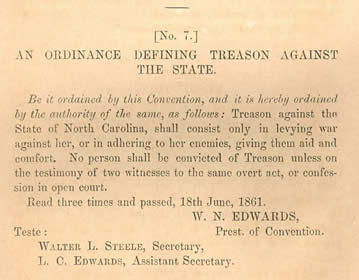

An Ordinance Defining Treason Against the State: Amendment to North Carolina Constitution,

read three times and passed 18 June 1861:

“Be it ordained that by this Convention, and it is hereby ordained by the authority of the same that follows:

Treason against the State of North Carolina, shall consist only of levying War against her, or in adhering to

her enemies; giving them aid and comfort. No person shall be convicted of Treason, unless on the Testimony

of two witnesses to the same overt act, or on confession in open Court.”

The United States and Confederate States Constitutions:

To further understand what constitutes a constitutional definition of treason, the following is presented:

The United States Constitution’s definition of treason (Article III, Section 3) states: “Treason against the

United States shall consist of levying War against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them Aid and Comfort.”

The Confederate States Constitution’s definition of treason (Article III, Section 3) states: “Treason against the

Confederate States shall consist only of levying war against them, or in adhering to their Enemies, giving them

Aid and Comfort."

Both Constitution’s were identical in language, both defining treason as against an individual State,

not a federal or confederate government or nation. Note the word "them."

John Brown Executed for Treason Against Virginia:

As an example, John Brown was hung by the State of Virginia in October, 1859 after being tried on

a charge of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, his intent being the overthrow of Virginia’s government

and inciting rebellion within the State. His act of treason against Virginia was not an act of treason against the

other States, and did not involve the United States government except in assisting in Brown’s capture.

Colonial Examples:

Peter Mallet:

A Connecticut-born (1744-1805) merchant who in 1765 was purchasing African slaves on the

Guinea coast for transport and sale in the West Indies for large profits. He established himself as a commission

merchant at Edenton, and later to Wilmington where he became a prominent merchant by 1769. In 1775 he was

ordered by the Wilmington Committee of Safety to return Negro slaves he brought as this was in violation of

the Continental Association’s agreement to not accept British imports. During the British occupation of the State,

Cornwallis was supplied with provisions by Mallet and he freely moved behind British lines. In January 1782 he

surrendered to State authorities and was charged with and tried for treason against North Carolina.

Sergeant Thomas Peters:

A soldier in the British Black Pioneers, formerly a slave in the lower Cape Fear who

joined British forces in 1776 and fought against North Carolina independence – evacuated from New York to

Nova Scotia in 1783. In 1785 a ship from Nova Scotia docked in New Bern and when it was learned that many of the

seamen aboard had aided the enemy in the late war, the Legislature asked the governor to arrest them.

Governor Richard Caswell ordered the sheriff of Craven County to detain 10 of the crew for treason.

At Savannah in December, 1778, African slave Quamino Dolly acted as a guide for the British forces laying siege

to the city and led them through an unguarded passage to the rear of the American army. The garrison was caught

by complete surprise, routed, and lost half its number to death, drowning and capture.

The War Between the States:

LIncoln's Proconsul -- Edward Stanly:

Diary Entry, June 12, 1862:

"[Edward] Stanly, the renegade, the traitor governor, appointed by Mr. Lincoln to rule his native State,

finds the way of the transgressor hard. He has stopped the Negro schools as being contrary to the

Statute Law of North Carolina, by which he has offended his Northern masters, but with a strange

inconsistency he ignores the fact (of which Mr. (George Edmund) Badger has reminded him however) that

his being here, as Gov, is as much an infringement on our rights, for the Laws of N.C. provide for an

election of the Gov by the people.

He said that if there was one man in N.C. whom he regarded more than another, one man whom he loved,

that man was Richard S. Donnell, & yet the first sight which greeted him on stepping ashore at New Berne

was the coffin of Mr. Donnell's mother with her name & the date of her birth & death cut on it, waiting shipment

to NY, her remains having been thrown out to give place to the body of a Yankee officer!

Such is our foe."

(Diary of a Secesh Lady)

Buffaloes: Thieves & Outlaws in Bertie County:

At least 805 Bertie Countians served honorably in defense of North Carolina during the War Between

the States; 63 would desert and adhere to the enemy. More than two hundred Bertie men would serve in

the First and Second Regiments North Carolina Union Volunteers, the equivalent of Tories serving the

British during the Revolution.

Upon the capture of Plymouth in 1863 by Major-General Robert F. Hoke of Lincolnton, twenty-two North Carolina

deserters found in Northern ranks were executed at Kinston. Many blue-clad North Carolinians captured at Plymouth

hid their identity and claimed to be assigned to other Northern regiments to escape execution – explaining how some

21 Bertie County men died at Andersonville. Author Thomas notes that “sufficient evidence exists that a number

of the [captured] North Carolinians “assumed the roles” of Northerners.”

Charles Freeman of Bertie County enlisted in Company C, First Regiment North Carolina Union Volunteers,

mustered in as private on 23 July, 1862 at age eighteen. Many North Carolinians who defected to Northern forces

were said to have done so to escape Confederate military service and defense of their State; perhaps most adhered to

the enemy to protect their families and property in enemy-occupied North Carolina.

John B. Harrell, Zadock Morris, Benjamin F. Jones, Nazareth W. Parker and Isaac Parker were among the men

who went over to the enemy, as well as David, George and William Hoggard. It is claimed that these men wished

to avoid Confederate conscription, yet were willing to accept military service with the enemy.

Confederate deserter John “Jack” Fairless of Gates County organized, with the endorsement of Northern

authorities, a company of fellow deserters and draft-dodgers “who would become notorious for their renegade

activity.” Confederate military personnel and citizens in general scornfully referred to the men who served in

Fairless’s company, as well as those in other eastern North Carolina Union units, as “Buffaloes”; the term

became synonymous with “thieves” and “outlaws.”

“Even Union military leaders in the area held [Fairless] in low regard.…[and referred to them as]

“our home guard thieves.” Fairless was a habitual drunk and was shot dead by a deserter from the

Nineteenth North Carolina Regiment, James Wallace, on October 20 [1862].

Littleton Johnson, a deserter from the Thirty-second North Carolina Regiment contacted a Northern captain

to offer his services in organizing another regiment of North Carolina deserters to serve the enemy. Johnson had

by then already recruited William Thomas, John T. Cale, and William A. Lawrence. David Thompson deserted from

the Eleventh North Carolina Regiment in January 1863 to become a paid recruiting agent for the enemy at Plymouth.

He was paid 50 cents per day for his services and recruited a number of Bertie County slaves

for the Northern navy. (Thomas)

Many of General Robert F. Hoke’s 2400 prisoners after the battle at Plymouth were sent to

Andersonville in Georgia, the North Carolinians among them desperately claimed to be members of

Northern units – to avoid being hanged as deserters and traitors to their State and families.

Abandoning Every Principle of Patriotism:

“During [Hoke’s] unhappy retreat from New Bern, Pickett had happened to be near a group of the Union

soldiers captured during the campaign. An officer of the Sixth North Carolina remarked, “They belong to my

company.” Overhearing the comment, Pickett was enraged. He screamed, “You damned rascals, I’ll have

you shot, and all the damned rascals who desert.”

As the prisoners were led away, Pickett told those around him, “We’ll have a court martial on these fellows

pretty soon, and after some are shot, the rest will stop deserting.” Almost as soon as the retreat was over,

Pickett ordered a court-martial, composed of Virginia officers, to convene at Kinston. Twenty-two of the prisoners,

all members of the First and Second Regiments, North Carolina [Northern] Volunteers, were hurried

before the tribunal.

Charged with desertion, the men were convicted and sentenced to die by hanging. Pickett summarily approved

the death warrants, and Hoke was ordered to execute the sentences.

While awaiting their execution…..On February 5, Hoke requested that Chaplain Paris visit two deserters who

were destined to be the first hanged. Paris found the captives to be the “most hardened and unfeeling men I

ever encountered.” These two men, known as William Haddock and William Jones, were hanged publicly

in the presence of Confederate soldiers and civilians.

Over the course of the month, the other twenty condemned men were taken to the gallows. After all the

death sentences had been carried out, the chaplain deemed it appropriate to deliver a sermon about

the executions to Hoke’s brigade. In his discourse on Sunday, February 28,

Paris asked Hoke’s soldiers,

“But who were those twenty-two men whom you hanged upon the gallows? They were your fellow beings.

They were citizens of our own Carolina. They once marched under the same beautiful flag that waves

over our heads, but in an evil hour, they yielded to mischievous influences, and from motives or feelings

base and sordid, unmanly and vile, resolved to abandon every principle of patriotism, and sacrificed

ever impulse of honor, this sealed their ruin and enstamped their lasting disgrace.”

Hoke’s personal sentiments about the executions were manifested when Bryon McCullom called on the

general to seek an order for the body of his brother-in-law, in order to bury it. When Hoke asked if he wanted

to bury the executed man in a Yankee uniform, McCullom responded in the affirmative. Hoke then

expressed surprise that “so respectable a man would bury his brother-in-law in a Yankee uniform.”

(General Robert F. Hoke, Lee’s Modest General, pp. 120-122)

Seizing Slaves for the Military

Black Troops From North Carolina in Northern Regiments:

“In May, 1863 Federal military authorities at New Bern began organizing the First Regiment North Carolina

Colored Infantry. Twenty-seven Bertie County blacks enlisted in the new regiment [from] May 20 through May 28.

During May and June, thirty-three Bertie County blacks enlisted in the regiment, which was formally organized

in June 1863. Forty-three Bertie County blacks enlisted in the second “colored’ regiment between

June 24 and August 3.

Escape to an Uncertain Future

Black plantation hands and their families would often hear of the freedom offered by the enemy, just

as Lord Dumnore had proclaimed in his emancipation decree in 1775. Then, Negro slaves fled to British lines to

join them in fighting against the colonists independence; during the WBTS, some did the same in fleeing to

enemy ships who were only interested in infromation about North Carolina's defenses and military movements.

“The desertion of Negro slaves as “Intelligent Contrabands” by the [enemy's] coasting cruisers

formed an occasional incident in the records of their official logs; but it is a noteworthy fact,

deserving honorable mention, that comparatively few of the trusted Negroes upon whom the

Confederate Army relied for the protection and support of their families at home were thus found wanting.

A pathetic and fatal instance is recalled in the case of a misguided Negro family which put off from the

shore in the darkness, hoping that they would be picked up by a chance gunboat in the morning.

They were hailed by a cruiser at daylight, but in attempting to board her, their frail boat was swamped,

and the father alone was rescued, the mother and all the children perishing.”

(Chronicles of the Cape Fear, James Sprunt, Edwards & Broughton, 1916, p. 392)

Aiding and Adhering to the Enemy -- William B. Gould:

Born in 1837 to an Englishman and slave mother, Gould was raised on the Nicholas Nixon plantation

north of Wilmington and being trained as a plasterer by his owner, hired out to work on homes in town.

He worked on the Dr. John D. Bellamy home at the corner of Fifth and Market Streets in the late 1850s,

employed by the free black carpenters who regularly used slave labor for their construction crews.

In late September, 1862, Gould and seven other slaves left their homes and families and rowed down

the Cape Fear River and across the bar to an enemy blockading ship. He then enlisted in the Northern

navy, providing aid and guidance for intelligence gathering and raiding parties which attacked the

important North Carolina salt production facilities along the Cape Fear coast.

Nearby, Fort Fisher’s commander, Colonel William Lamb, was to find that his trusted slave Charles Wesley

fled to the enemy in May, 1864. Wesley provided invaluable information to the enemy regarding the fort's

construction, armament and troop strength, greatly undermining the defense

of the Cape Fear River and North Carolina. Gould remained in the North after the war,

and is buried in Dedham, Massachusetts in 1923.

Aiding and Adhering to the Enemy -- Abraham Galloway of Brunswick County:

Born a slave in Brunswick County, Abraham Galloway abandoned his family in 1857

and ended up in Ohio, where he would become “a militant abolitionist” (Evans, p. 110).

He returned to North Carolina in late 1862 with enemy troops, gathering information and

capturing slaves to serve in Northern regiments. Of this enemy occupation, “A lady in Elizabeth City

wrote in early 1863 that over two hundred Negroes daily went out “to maraud the country,” which

added greatly “to the terror and alarm of the women and children.”

After the war Galloway was located in New Bern, then moved to Wilmington in 1867 to

organize the Republican party through its large black population. He served as a delegate from

New Hanover County at the Raleigh constitutional convention in January 1868 that replaced

North Carolina’s historic constitution. Galloway’s contemporaries regarded him as being

“of exceedingly radical and Jacobinical spirit,” who “favored heavy taxation of large

estates." (Evans, pp. 110-11).

Historian Hamilton wrote of the 1868 Republican-majority General Assembly of which Galloway

was a part, that “The ignorance and prejudice of the majority of Republicans made them easy

prey for the corrupt minority of the party which at once assumed leadership in the body.

Venality was profitable and many who did not belong in such company were betrayed into

joining in the spoliation of the State.” (Hamilton, p. 349)

Galloway was also a strong supporter of Northern Gen. Milton S. Littlefield, a notorious postwar

carpetbagger and Union League leader who orchestrated fraudulent railroad bond schemes

which impoverished the already prostate State. The Raleigh Sentinel reported that when

Littlefield left North Carolina he had “in his possession as he departed $4,000,000 in State

bonds, the un-squandered portion of [the original] $7,000,000.”

The Radical Republican-dominated Reconstruction machine helped elect him as a State senator

in April 1868, and reelected him in 1870. That year he narrowly escaped an attempt on his life,

but died shortly thereafter of jaundice and bilious fever. The Wilmington Daily Journal wrote of

his death on 2 September 1870: “Mortuis nil nisi bonum,” “of the dead nothing but good.”

(Sources: Powell, Hamilton, Evans, Daniels)

High on the list of those North Carolinians who adhered to the enemy and waged war upon the State

was the infamous George W. Kirk, a murderous leader of fellow deserters and bushwhackers.

Born in Greene County, Tennessee, he enlisted in Confederate service but deserted at the first

opportunity and fled to the enemy. The corrupt Reconstruction Governor W.W. Holden later utilized

Kirk to suppress North Carolinians who resisted his bayonet rule.

Kirk’s Bushwhackers and Traitors

“My father was Captain Thomas Anderson Long, C.S.A. Near the end of the war he was stationed

at Camp Vance, near Morganton, in Western North Carolina, where he was serving as captain

in the commissary. He was captured there when this small post, a training camp for conscripts,

fell into the hands of Colonel Kirk and his band of guerillas. These men were a motley crew

from east Tennessee; among them deserters from both armies, whose god was plunder and

whose sport was murder; a dozen or so Cherokee Indians gave color and flavor to the outfit.

Kirk and his men came down stealthily through the mountain trails. The post was too weak to do

anything but capitulate. Loading his plunder on forty horses and mules, Kirk took his booty and his

prisoners and made a dash back to the mountains; but he was forced from time to time to fight off

pursuing squads of [Home Guard] men – old men and young men – who had collected quickly.

In these skirmishes it was Kirk’s practice to place the prisoners in his own front rank so they might

be killed unwittingly by their own comrades. He was heard to say,

“Look at the damn fools shooting their own men.”

Some of the prisoners were shot down, but my father was fortunate to escape unhurt.

When the prisoners had crossed the mountains and had reached the Tennessee River,

they were distributed to various prisons, the officers being sent to Johnson’s Island in Lake Erie.

[The prisoners] felt lucky to [be alive]…Kirk himself would probably have treated the prisoners

more harshly if the Union general in command at Knoxville had not placed a restraining hand on Kirk.

Kirk raided the Carolina mountains many times and in many directions. Women and children were

the worst sufferers. Many of the men were in the army, and in their absence the women folk did

even the plowing; when Kirk took their cows and pigs and chickens, there wasn’t much left to live on.

If you wished to see men in this region bristle, all you need do is mention the name Kirk.”

(Son of Carolina, Augustus White Long, Duke University Press, 1939, pp. 11-13)

Adhering to the Enemy -- Charles H. Foster at Murfreesboro

Charles H. Foster (1830-1882) was a native of Maine who in 1857 had become editor of the

Norfolk, Virginia “Southern Statesman,” a Democratic organ. At the end of 1859 he had purchased

the small Murfreesboro, North Carolina weekly, “The Citizen.” Elected an alternate to the Democratic

National Convention in Charleston in 1860, he also represented North Carolina at the Baltimore

convention that year. He championed the nomination of John C. Breckinridge.

In October 1860 Foster had a change of heart, sold The Citizen and applied for employment with

the US Post Office in Washington, and took a clerkship position in February 1861. Before leaving

North Carolina Foster had become a strong Union man who opposed the secession of the State,

probably to ensure his new federal government position. Returning to Murfreesboro in May 1861

to visit his wife and infant daughter, he was suspected of being

a Northern spy and forced to flee northward.

Back in Washington, Foster claimed to represent all Unionists in North Carolina and attempted to

gain a seat in the special session of Congress in July 1861. He “contrived a series of letters,

postmarked from various North Carolina towns, representing that Unionism was rife throughout

the State. The letters also publicized a “Unionist election” in North Carolina in August for

the purpose of sending representatives to Congress.”

Foster was absent from Washington in July and August to create the impression of returning to

his imaginary Unionist constituents, and then reappeared in September “bearing credentials attesting

to his election to Congress by the Unionists” of the State.

Unable to obtain elective office to represent enemy-occupied areas of northeastern North Carolina,

Foster eventually found work as a recruiting agent for the invading army. He raised most of the

so-called “First North Carolina Union Regiment,” and was appointed Lieutenant-Colonel of the

“Second North Carolina Volunteers. The latter position he held until banished from the

army for “inefficiency as an officer” and complaints to Washington. The recruitment of

North Carolina men was gained by threats of retaliation against their families and destruction

of their farms and property. Merchants were required to take oaths of allegiance to the

Northern government to keep their shops open, and fishermen required to

do the same to continue their occupation.

Foster returned to enemy-occupied Murfreesboro late in the war where he practiced law, dabbled

in Republican politics, and was an “erstwhile correspondent” for the New York Herald and other

papers. In 1878 he and his family relocated to Philadelphia.

(Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, William S. Powell,, 1986)

While a North Carolina State Legislator in 1902, future Governor Locke Craig debated North Carolina’s

Republican US Senator Jeter Pritchard at Charlotte and denounced the Republican practice

of rewarding those who had committed treason against North Carolina.

Republicans Rewarding Traitors with Pensions

[The Republicans complain that] two hundred thousand dollars went to pension the Confederate

soldiers. We will take care of these old veterans, we owe them a debt of gratitude. In the wreck

and ruin of war we were rich in the priceless heritage of their memory.

“These were men whom death could not terrify, whom defeat could not dishonor.” They glorified the fallen

cause by the simple manhood of their lives and by the heroism of their death. They have cast over

the South the glamour or an immortal chivalry and consecrated the cause of Dixie with the blood

of an immortal sacrifice. It was devotion like this that made the South, though torn and bleeding,

beautiful and splendid in her desolation, and in her woe.

For forty years they have been the builders of the New South and the projectors of her larger destiny.

The Federal Government provides for the soldiers that followed its flag. That is right. We will provide

for the soldiers of the armies of the “storm-cradled nation that fell.”

When Senator Pritchard was a member of the Legislature in 1895 he and his party voted against

giving one cent of pension to the needy heroes that had hobbled home on crutches from Appomattox.

There is one class of men whom we do not believe in pensioning – the deserter. There are men here

who remember the last two years of the war. The world was against us. Armies were crashing down

upon us like a ring of fire. Sherman was marching to the sea and leaving behind him ashes and desolation.

In that time there were men whose courage never faltered.

Ragged and hungry and bleeding they stood in the trenches around Richmond and Petersburg.

They stood with an unfailing devotion, though sometimes they knew that their little ones at home

were living on the corn they picked up from the wagon ruts of the invading armies. They died

remembering Dixie like the Greeks remembering Argos – in the language of the old song:

“While one kissed a ringlet of thin gray hair and one kissed a lock of brown.”

But there were some who did not stand. Traitors and deserters they were. They turned their backs upon

the only home and country that they ever had. They sneaked through the lines. They threw away their

old gray uniform and put on the blue. They came back to shoot and kill, to rob the defenseless wives

and mothers of their comrades who were fighting and dying at the front; to burn their homes

and to murder the innocent.

To these men Senator Pritchard has given a royal pension. He said to the hero of the Confederacy

that he might starve, but with the money of the honest people he feeds and clothes the deserter.

Yes, I denounce this in the name of the forty thousand sons of North Carolina who sleep tonight

beneath the sod in the battle-scarred bosom of old Virginia. I denounce it in the name of the men

who rushed defiant of death through the storm of Chickamauga and Gettysburg. In the name of

every Confederate soldier I denounce it. In memory of the women who were robbed and the

men who were murdered I denounce it. In the name of all brave men who love courage and

despise cowardice, who believe in fidelity to comrades and in love for home and in loyalty to

a great cause, I denounce this infamous act. I do not stand alone.

Here is the resolution of the last Reunion of Confederate Veterans of North Carolina:

“Resolved, That we condemn and denounce the Act of Congress which rewards treachery and perfidy

in giving pensions to Confederate deserters for fighting against their former flag and comrades.”

The judgment of the South is that the party that starves the soldier and pensions

the deserter should be accursed forever."

(Speech (excerpt) of Hon. Locke Craig, Joint Debate with Sen. Jeter Pritchard, October 9, 1902,

Memoirs and Speeches of Locke Craig, Hackney & Moale Company, 1923, pp. 85-88)

Sources:

Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, William S. Powell, 1986

The Black Experience in Revolutionary North Carolina, Jeffrey Crow

The Savannah, Thomas L. Stokes

General Robert F. Hoke, Lee's Modest Warrior, D.W. Barefoot, 1996

Divided Allegiances, Bertie County During the Civil War, Gerald W. Thomas

Reconstruction in North Carolina, Joseph DeR. Hamilton, 1914

Ballots and Fence Rails, W. McKee Evans, UGA Press, 1995

Prince of Carpetbaggers, Jonathan Daniels, J.B. Lippincott, 1958

Copyright 2012 North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission