North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

A Plea For Saving the Union:

Jefferson Davis

"Our fathers formed a Government for a Union of friendly States; [that] Union of friendly States has

changed its character, and sectional hostility has been substituted for the fraternity in which the

Government was founded.

But I call upon all men who have in their hearts a love for the Union, and whose service is not merely of

the lip, to look the question calmly but fully in the face...How, then have we to provide a remedy?

By strengthening this Government? By instituting physical force to overawe the States, to coerce the

people?.....No, sir; I would have this Union severed into thirty-three fragments sooner than have that

great evil befall constitutional liberty and representative government.

Our government is an agency of delegated and strictly limited powers. Its Founders did not look to its

preservation by force; but the chain they wove to bind these States together was one of love and mutual

good offices. The remedy for these (sectional) evils is to be found in the patriotism and affection of the

people, if it exists; and if it does not exist, if is far better , instead of attempting to preserve a forced and

therefore fruitless Union, that we should peacefully part and each pursue his separate course. “

(Senator Jefferson Davis, Speech to the United States Congress, excerpt, December 10, 1860)

North Carolina's Peace Commissioners

Seeking “to effect an honorable and amicable adjustment” of the sectional difficulties “on the basis of

the Crittenden Resolutions as modified by the legislature of Virginia,” North Carolina sent representatives

to the Southern government forming at Montgomery, Alabama, and to the Peace Commission which assembled

in Washington City from 4 February to 27 February, 1861. The Legislature on January 26 appointed as

commissioners Hon. Thomas Ruffin, Hon. D.M. Barringer, Hon. David S. Reid, Hon. John M. Morehead,

Hon. David L. Swain, J.R. Bridgers, Matt W. Ransom, and George Davis. Of this group Swain, Bridgers

and Ransom were sent to Montgomery to observe the formation of the new government. Swain penned

the report of the commission to Montgomery and described the flattering reception accorded them, though

they lacked official sanction to participate as anything but spectators.

Swain noted "that only a very decided minority of the community in these States are disposed at present

to entertain favorably any proposition of adjustment which looks towards a reconstruction of our national union."

The Washington Peace Congress

The Peace Congress sat in closed session with ex-President John Tyler at its head trying to find solutions

to the secession crisis which already saw several States leave the Union, but concluded without finding a

reasonable compromise between the sections.

The pro-secession Wilmington Journal of 21 February opined that the seceding States would not accept the

Crittenden compromise, stating that “it is too late in the day to talk about compromises…The border Southern

States must decide to which Confederacy they will attach themselves…There can be no half-way course now.”

The Wilmington Daily Journal of March 4 reported:

“George Davis, Esq., addressed his fellow-citizens on last Saturday, March 2, at the Thalian Hall in reference

to the proceedings of the late Peace Congress, of which he was a member…the hall was densely crowded by

an eager and attentive audience. Mr. Davis said he had gone to the Peace Congress to exhaust every

honorable means to obtain a fair, an honorable, and a final settlement of existing difficulties. He had done so

to the best of his ability, and had been unsuccessful, for he could never accept the plan adopted by the

Peace Congress as consistent with the rights, the interests, or the dignity of North Carolina.”

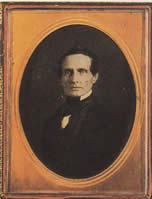

George Davis

Abraham Lincoln actually visited the Peace Conference while in session though he would not discuss any

peace initiatives. New York merchant William E. Dodge said blunt to him: “Then you will yield to the just

demands of the South…You will not go to war on account of slavery?” Lincoln responded vaguely:

“I do not know that I understand your meaning, Mr. Dodge. Nor do I know what acts or opinions may be

in the future---I will defend the Constitution as it is.”

The Peace Conference’s failure was widely attributed to Radical Republican insistence on its members

rejecting any compromise with the States of the South. At this same time, Lincoln’s incoming Secretary

of Treasury Salmon Chase openly declared that the Northern States “never would fulfill their obligations

under the Constitution in the matter of fugitive slaves.” This statement made many old time Southern Whigs

realize that there was but one alternative, and that was to quit the Union as the only way of saving

the Constitution of the Founders.

Up in Wilson, North Carolina, a Southern Rights meeting at the county courthouse resolved that it was

North Carolina’s duty, as well as every other [Southern] State, “to detach itself from the old confederation

whose constitution has been violated by a majority of the States composing it…and join the

brotherhood of the South.”

Virginia’s Peacemaker, John Tyler:

Former President John Tyler forewarned his countrymen in February 1861 of the result of a fratricidal war,

though his vivid description of war and bloodshed did not inspire his Northern friends toward peaceful

settlement of the issues. Born in 1792 during Washington’s presidency, Tyler exhibited a knowing perspective

of the Founders’ understanding of the Union to combat Northern revolutionary doctrines. His father was also

a good friend of Jefferson, a frequent guest to the Tyler household.

“After a few days’ rest…[former President] Tyler returned to Washington in time to be present at the

opening session of the Peace Convention. He was anxious, he said, to win the honor of a peacemaker and a

healer of the breach in the Union. He had worn all the honors of office through each grade to the highest

and no wanted to crown his career with the distinction of having restored the “Union in all its plenitude,

perfect as it was before the severance.”

[He] regretted that the Virginia Assembly in its call had included all the States. As the seceded States

would not send delegates, the convention would be dominated by the Northern States. His plan was to

have a convention of the border States – six slave and six free. To this convention two delegates each

should be sent from the Northern States of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan,

and the Southern States of Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee , and Missouri.

These twelve States were in a better position than any others to act as arbiters of the dispute, and

their recommendations would probably be accepted by both sides. If an agreement could not be reached,

peaceable separation might be agreed upon. This would be preferable to a fratricidal war. For if one section

should conquer the other in that war it would not gain anything.

“The conqueror will walk at every step over the smoldering ashes and beneath crumbling columns. States

once proud and independent will no longer exist and the glory of the Union will have departed forever.

Ruin and desolation will everywhere prevail, and the victor’s brow, instead of a wreath of glorious evergreen

such as a patriot…wear[s], will be encircled with withered and faded leaves bedewed with the blood of the

child and its mother and the father and the son. The picture is too horrible and revolting to be dwelt upon.”

If the recommendations of this smaller convention were not accepted by both sides, this would prove

that the restoration of peace and concord was impossible. In that event the Southern States should

hold a convention as a last resort. This convention should take the Constitution of the United States

and incorporate into it such changes as would be necessary to safeguard the rights of the South. These

guaranties, however, should not go “one iota beyond what strict justice and the security of the South require.”

The Constitution so amended should be adopted by the convention and then an invitation issued to the other

States to join them under the old Constitution and flag.”

(John Tyler, Champion of the Old South, Oliver Chitwood, American Historical Association, 1939, pp. 439-440)

Zebulon Vance Looks Back

"The experience of the commissioners, and the adverse vote a few weeks later on the [North Carolina secesssion]

convention proposal, serve to confirm the words of Governor Vance in 1875 when he described the temper of

the majority of North Carolina people during the weeks prior to April, 1861. After reciting the fact that

"seven-tenths of our people owned no slaves and, to say the least of it, felt no great and enduring enthusiasm

for its [slavery's] preservation, especially when it seemed to them that it was in no danger," Vance glorified

the chivalric devotion of his native State when he declared: "She was the last to move in the drama of

secession, and went out at last more from a sense of duty to her sisters and the sympathies of

neighborhood and blood than from a deliberate conviction that it was good policy to do so."

(North Carolina, The Old North State and the New, Archibald Henderson, 1941)

Republicans in No Mind to Prevent War:

“In the dark hours of January, 1861, when the Cotton States were withdrawing from the Union,

the eyes of many turned to [George Davis] for inspiration and guidance; and when the North Carolina

Assembly appointed delegates to a National Convention, seeking some settlement of the sectional

issues that would restore and preserve the Union, Mr. Davis was selected as one of them, his associates

being Chief Justice [Thomas] Ruffin, Governor [ John] Morehead, Governor [David] Reid, and Daniel M. Barringer.

The Convention met at Washington February 4th, and was attended by delegates from nearly every State

except those on the Pacific, and those that had seceded. At the outset, however, Salmon P. Chase

negative the idea that the North would make any concession, declaring that “the election must be

regarded as a triumph of principles cherished in the hearts of the people of the Free States, while

Mr. Lincoln urged his friends, “No step backward.”

All resolutions were referred to a grand committee. Nine days passed with no report. At length,

on the tenth day, the committee reported a proposition for a constitutional amendment composed

of seven sections. Two weeks elapsed in secret session, the South awaiting the result of its appeal

to the Union sentiment of the North – in anxious suspense.

On the 27th Mr. Davis telegraphed: “The Convention has just adjourned. North Carolina voted against

every article except one.” In the Convention each State had a single vote, cast by a majority of its

delegates. Davis, Reid and Barringer determined the action of North Carolina, Ruffin and Morehead

accepting the propositions, not because they were at all satisfactory, but with the hope of preventing war.

The Republicans in Congress, however, had no mind to prevent war. [Zachariah] Chandler, of Michigan,

gave voice to their purposes when he declared in the Senate: “No concession; no compromise; aye!

Give us strife, even blood, before a yielding to the demands of traitorous insolence!”

Union sentiment was in the ascendant in North Carolina [in February, 1861]; but among the people of the

Cape Fear section the hope of an amicable adjustment had almost faded away. On the return of Mr. Davis

the citizens of Wilmington invited him to address them, and he immediately complied. He declared that

he had gone to the Peace Convention determined to exhaust every honorable means to obtain a fair,

honorable and final settlement of existing difficulties. He had striven to that end, to the best of his

abilities, but had been unsuccessful, for he “could never accept the plan adopted by the Convention

as consistent with the rights, the interests, or the dignity of North Carolina.”

The recommendations of the Peace Convention, as favorable as it was to the North, however, [were] not

accepted by the malignants in Congress. President [James] Buchanan had declared that he would never

embrue his hands in the blood of his countrymen; but after a fortnight of vacillation, war was determined

on by Mr. Lincoln and his cabinet….When it came – when the only question presented was whether we

should fight with or against the South – all differences among our people ceased.”

(George Davis, Attorney-General of the Confederate States, Address Delivered Before the Supreme Court

of North Carolina, October 19, 1915, Samuel A’Court Ashe, Edwards & Broughton Printing, 1916, pp. 9-10)

Copyright 2011, North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission