North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

“Of course I cannot give you much criticism upon the war, or the causes of our failure; nor can I attempt to

do justice to the heroism of our troops or of the great men developed by the contest. This is the business

of the historian, and when he traces the lines which are to render immortal the deeds of this revolution,

if truth and candor guide his pen, neither our generals nor our soldiers will be found inferior to any who

have fought and bled within a century."

Governor Zebulon Vance

Aftermath: Destruction & Military Rule

Witnessing the End at Chapel Hill:

“My very young eyes saw Joseph E. Johnston’s army pass through the old college town of Chapel Hill;

Sherman was hanging on its rear. As I stood by the side of the road with my mother, my hand in hers,

I was too young to see what my eyes saw, “the most pitiable sight I ever beheld,” she always said.

I did not know what it all meant, but I probably wondered why there were so many horses in one

place and why so many of them were limping. The end of the war was near, Lee had surrendered,

and Johnston’s surrender was only a matter of days. Ragged uniforms and barefooted men told

the story. The limping horses belonged to General Joe Wheeler’s cavalry.

After my father was captured and taken to prison on Lake Erie, my mother and I went to live with

Uncle John and Aunt Nancy, an elderly couple without children, on the Fred Hargrave plantation,

situated a mile from Chapel Hill in a crotch made by the roads from Durham

and from Raleigh as they approached the village.

The Hargrave Negroes still lived in their cabins and still put in crops of corn and cotton as

they had always done. Lincoln’s Proclamation had freed them many months before, but they

did not know what to do with their freedom; they did not know where to go or how to get there;

so they stood in their tracks, waiting for the future to turn its page.

One warm day [little Betsy Toler] sat under a tree fanning herself…[and] a Negro boy came running

in from the field, scarcely touching the furrows as he came. When he got in the yard,

he spluttered, “Yankees! The Yankees are coming!” Betsy, out of the corner of her eye

catching sight of a blue column, rushed to the house…landed in her feather bed, rolling

it over as a covering, and disappeared from sight.

A group of troopers – commonly called Sherman’s bummers – straggled away from the column,

rode into our yard, and began rummaging through the house without ceremony. As they went up

the stairs, their swords rattled against the steps – clank, clank, clank.

The first room they entered was Betsy’s. They jerked off the feather bed; there she lay fully swathed:

“Come here boys; here’s the dying Confederacy.” With a loud laugh they stalked into the next room.

They snatched me up asleep in a crib and ran their hands under the little mattress; they were too late

as Uncle John had already done the collecting and had buried the silver out in the orchard,

covering the spot over carefully with leaves.

After the crops had been laid by on the Hargrave plantation, we moved back to Chapel Hill and went

to live in the house on Rosemary Street where I was born. [Here] my father had kissed [my mother]

for the first time; here they were married, and here I first opened my eyes; it was in this house he said

a lingering goodbye when he put on his uniform; now we awaited his return from a Northern prison.”

(Son of Carolina, Augustus White Long, Duke University Press, 1939, pp. 4-11)

Nineteen Year-Old Major Walter Clark and Neverson Go Home:

General Johnston broke camp near Smithfield on April 10, and on April 12 reached Raleigh.

There it was learned that Lee had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. President Davis and his

cabinet had abandoned the Confederate capital at Richmond and arrived at Greensboro on April 11. While

not officially advised that the Army of [Northern] Virginia was no more…[Johnston] did not surrender…until

April 26. On May 2, 1865, at Bush Hill, near High Point, Major [Walter M.] Clark and what remained of the

third Junior Reserves were paroled and turned their faces sorrowfully homeward.

The next day Major Clark and his faithful Neverson began their weary horseback ride one hundred and fifty

miles to Ventosa [plantation]. On their way home they passed through Hillsboro and in sight of the military

academy from which Little Clark had gone so ambitiously and hopefully four years before. He knew that

[academy headmaster] Colonel [C.C.] Tew had been killed at Sharpsburg, but did not know until afterward

that every one of his instructors in the academy had gone to the war and either had been wounded or captured.

The lonely trek of these two boys, their minds numbed by harrowing memories, was enough to chill their hearts,

but there was worse to come.

When home was finally reached, there was no home – nothing but the land was there, and that covered with

a tangled growth of bushes and briars. The once great cultivated fields of cotton and corn were now a

wilderness of weeds. The slaves were wandering aimlessly through the neighborhood, and raiding

Federal soldiers had stolen the livestock. The invading armies had burned to the ground the spacious

Ventosa mansion, and its beautiful gardens had disappeared. All the happy memories of Walter’s childhood

here lay waste in ashes before his eyes. With an almost broken heart he turned to seek elsewhere for his

father and mother, his sisters and brothers, in the hope that he would find them alive.”

(Walter Clark, Fighting Judge, pp. 21-22)

General Bryan Grimes and the Reign of Terror:

“Grim scenes abounded as the homeward-bound North Carolinians rode South. One event in particular

must have made [General Bryan] Grimes wonder what was in store for him as a defeated soldier

without the means to fight back. According to Grimes’ astute traveling companion, Thomas Devereux:

“A few miles from the forks of the road we came to an old man, Loftin Terrel, his house was on the

roadside and he was knee-deep in feathers where [Sherman’s] bummers had ripped open the beds, a yearling

and a mule colt were lying dead in the lot; they had been wantonly shot.

Old man Terrel was sitting on his door step, he said there was not a thing left in the house and every

bundle of fodder and grain of corn had been carried off; that he had been stripped of everything he owned

and he had not a mouthful to eat. They had even killed his dog which was lying dead near the house.”

The Federals garrisoning the city issued orders forbidding former Confederates from wearing

their uniforms. For many this directive presented a difficult dilemma, for they had no other clothes to wear

and no money to purchase new ones. Charlotte [Grimes] responded to the order by covering her husband’s

brass uniform buttons with bootblack, a ruse Grimes described made him look as though he

was “in mourning for the Confederacy.” The ever resourceful Charlotte, despite Grime’s protestations, sold

several of her silk dresses for $100 and used the money to purchase his clothes. “It seemed to hurt him

to have to use this money,” explained Charlotte, “but I would take no denial.”

Grimes dealt with his illness and the “grief of the surrender” amid constant rumors of pending

retribution at the hands of the Yankee governors. “There was a report that they would hang all officers

above the rank of captain and all their property would be confiscated,” [wife] Charlotte recalled.

“We were living in a “Reign of Terror.”

They were also living with Charlotte’s parents in Raleigh during the summer of 1865, with the

former enemy visible everywhere. Charlotte remembered “a Yankee camp just across the street

from my father’s front gate by which he would have to pass…I would see them watch

him and hear them say, “there goes the rebel, Gen. Grimes.”

(Bryan Grimes of North Carolina, T. Harrell Allen, pp. 258-261)

A Petty Trick

“In a day or two authenticated information was received that both Lee’s and Johnston’s

armies had been surrendered on terms of agreement, and as I was included in the latter army,

I went to Columbus and obtained my parole. The terms of the surrender were that we were

not to be molested by the United States authorities so long as we obeyed the laws which

were in force previous to January, 1861, where we resided.

On my part, I was sworn “not to bear arms against the United States of America, or give

any information, or do any military duty or act in hostility to the United States, or inimical

to a permanent peace,” etc., and thus the war with the musket ended.

On reading my parole I discovered what seemed to me a petty trick, for it read “not to be

disturbed by the United States military authorities,” leaving me at the mercy

of the civil authorities to be indicted.”

(Two Wars, Autobiography of Gen. Samuel G. French, Confederate Veteran, 1901, pg. 309)

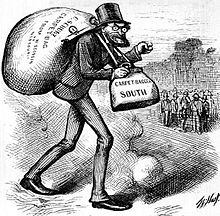

Reconstruction:

"In the wake of the civil rights revolution of the 1960s, for instance, the history of

Reconstruction was rewritten. But this was not because the discovery of new historical knowledge

required the revising of previously erroneous views. Rather, it was because the emergence of new

attitudes required the formulation of a new interpretation.

It is doubtful that present historians of Reconstruction “know” any more about it than writers

of the derided school of William A. Dunning. In fact, present writers, in many cases know

considerably less. They simply measure Reconstruction by a different scale of values.”

(Recovering Southern History, Clyde N. Wilson, Defending Dixie, page 2)

“Adventurers swarmed out of the North, as much the enemies of one race as the other,

to cozen, beguile and use the Negro. The white men were aroused by a mere instinct of self-preservation.”

Woodrow Wilson

"The carnival of corruption and fraud, the trampling down of decency, the rioting in the overthrow of the

traditions of a proud people, the chaos of hell on earth which took place beggars the descriptive powers of plain

history…I believe a committee of Congress, who took some testimony on this subject, estimated in 1871 the

amount of plunder which was extracted from the Southern people in about 5 short years---some $300 millions of

dollars in the shape of increased debt alone, to say nothing of the indirect damage inflicted by the many ways of

corruption and misrule which can not be estimated in money."

Governor Zebulon Vance

Hell is Empty and all the Devils are Here:

“As vultures sail in long lines from their roost (countless in numbers) to where the carcass is, so came in the

harpies and political adventurers to the carcass (the South) to embrace the colored citizens; and, hand in hand,

cheek by jowl, they entered the political arena and filled the capitols of the South. Every officer in the State from

governor to coroner was dismissed, and new appointments made.

The Legislatures became bacchanalian feasts to divide the spoils of office and increase the debts

of the States by selling State bonds to the amount of countless millions. They subsidized everything they could;

in short, they ate up or took possession of all that was left after the war ceased; and at last departed with

stolen wealth, and the execrations of all the honest people.

Perhaps in all the wide-world never again will be seen such malignant legislation, and mal-administration of law,

such trials in the courts…idleness of the laborers, immorality taught by men from the slums of Northern cities,

thirst for money, howling for office, insolence in office, creating anxiety of mind as to what a day might bring forth.

Add to this the formation of loyal [Union] league societies of Negroes, by politicians swearing them to

obedience to orders, bands of brothers and sisters, composed of blacks under white villains, to burn our towns and

murder the whites, the Ku Klux Klan of the whites for protection, and other kindred vexations and trials that made

the South the home of the spirits of pandemonium; so one could truly exclaim with Ariel:

“Hell is empty and all the devils are here.”

(“Two Wars; The Autobiography of Gen. Samuel G. French, CSA”, Confederate Veteran, 1901, pp. 331-333)

The South in 1865 voluntarily laid down its arms in deference to the Northern Constitution and its laws,

though it experienced what the wife of Gen. Bryan Grimes called a “reign of terror.” She reported that

“there was a report that they would hang all officers above the rank of captain and

all their property would be confiscated.”

The South from Country to Colony

“We stacked eight thousand stands of arms, all told, artillery, cavalry, infantry stragglers, wagon-rats,

and all the rest, from twelve to fifteen thousand men. The United States troops, by their own estimate,

were 150,000 men, with a railroad connecting their rear with Washington, New York, Germany, France,

Belgium, Africa, “all the world and the rest of mankind,” as General [Richard] Taylor comprehensively

remarked, for their recruiting stations were all over the world, and the crusade against the South,

and its peculiar manners and civilization, under the pressure of the “almighty American dollar,”

was as absolute and varied in its nationality as that of “Peter the Hermit,” under the

pressure of religious zeal, upon Jerusalem . . . .

Those who took a serious consideration of the state of affairs, felt that with our defeat we had

as absolutely lost our country – the one we held under the Constitution – as though we had been

conquered and made a colony of by France or Russia. The right of the strongest – the law

of the sword – was as absolute at “Appomattox” that day as when Brennus, the Gaul, threw

it in the scale at the ransom of Rome.

So far, it was all according to the order of things, and we stood on these bare hills men without a country.

General Grant offered us, it was said, rations and transportation – each man to his native State, now

a conquered province, or to Halifax, Nova Scotia. Many would not have hesitated to accept the offer

for Halifax and rations; but, in distant Southern homes were old men, helpless women and children,

whose cry for help it was not hard to hear. So, in good faith, accepting our fate, we took allegiance

to this, our new country, which is now called the “United States,” as we would

have done to France or Russia.

With all that was around us – the destruction of the “Army of Northern Virginia” and certain defeat

of the Confederacy as a result – no one dreamed of what has followed. The fanaticism that has influenced

the policy of the Government to treat subject States – whose citizens had been permitted to take an oath

of allegiance, accepted them as such, and promised to give them the benefit of laws protecting person,

property and religion – as the dominant party in the United States has done, exceeds belief.

To place the government of the States absolutely in the hands of its former slaves, and call their “acts” “laws;”

to denounce the slightest effort to assert the white vote, even under the laws, treason; and finally, force the

unwilling United States soldier to use his bayonet to sustain the grossest outrages of law and decency

against men of his own color and race! . . .

. . . [T]his has gone on until, lost in wonder as to what is to come next, the Southern white man

watches events as a tide that is gradually rising and spreading, and from which he sees no avenue

of escape, and must, unless an intervention almost miraculous takes place, soon sweep him away . . . “

(The Falling Flag, E.M. Boykin; Empire of the Owls, H.V. Traywick, Jr., pp. 295-296)

“North Carolina ran her carpetbaggers as far as her college campuses.

There they swapped their title “Scalawag” for doctorates and there they have ever remained,

screaming “academic freedom.”

R. Carter Pittman

The Raleigh Sentinel on Carpetbaggers"

The history of legislation in North Carolina would form one of the strangest books that has ever been published.

It would reveal an amount of fraud, venality and recklessness perfectly unparalleled, we venture to say, in

the history of legislation in any age or country. If ever before there was a time demanding the most

scrupulous and watchful economy, it is the present.

And yet, in the face of wide-spread ruin and dismay; in the face of repeated failures in crops

and a disorganized system of labor; with depression and anxiety in every house-hold, the members of

the present legislature have exhibited the utmost disregard of the actual condition of our people, and have

wantonly and wickedly and with malice prepense concocted a system of taxation, that not only outrages public

opinion, but fastens, it may be, for all time, burdens perfectly unbearable and destructive upon the

landed proprietors of the State.

These representatives of the people---these public servants “so-called”---these incapable and

indifferent legislators, met in Raleigh and deliberately set to work to despoil the State and add ten-fold

distress to her people. They enter upon a plan of spoilation as effective in its results as was the

“bumming” of Sherman’s scoundrels. They lend themselves to the wild schemes, listen with itching ears to the

rapacious demands of wild cat combinations, wink at corruption and profligacy, indulge in vice and immorality,

and conspire to paralyze the best interests of the State, to drive away capital, to keep capital from

coming into the State and to lay taxes that can not be borne…Railroad schemes without number, a

continued waste of public funds, and taxes at once oppressive and thoroughly ruinous are the results

of their six months stay in Raleigh. They have done nothing but evil and are an offense to every just and honest man.

They deserve, and they shall receive the hearty execration of a long suffering, industrious and frugal people.

But we refer to those harpies, some from the Northland, but many native and to the manor born,” who

preyed upon our people, and with cormorant appetites essayed to suck the very life-blood from the

emaciated form of our old Mother. Carpet-baggers who came unbidden and who have fairly battened upon

the political garbage that has been thrown to them; obsequious time-servers and trimmers who have

played the sycophants for filthy lucre---these are the creatures who have wickedly conspired against the people

of North Carolina, and have sought to ruin them by the most oppressive taxation---these are the creatures who

amid the troubling of the political waters have been spawned in our Legislative halls, and who ought to be

denounced and shunned as you would a leper.

They are political lepers and taint the whole political atmosphere.”

(Raleigh Daily Sentinel, April 16, 1869)

Carpetbag Rule Over Ruin

"In the formation of new governments primarily, the Negro who had no right to vote was permitted to do so by

military force. The historical inquirer will likewise learn that during the time the South was being thus

plundered by the carpetbaggers through the ignorance of the Negroes in the Southern department of the

party of purity and free elections, the home office was doing a business, which reflected no mean luster

on the active and energetic Southern branches. The system of levying contributions upon all Federal officeholders

for corrupt political purposes was inaugurated and set going with efficiency and success.

The carpetbag rulers were infinitely worse than the Negroes. The evil propensities of the one were directed

by intelligence, and the ignorance of the other became simply the instrument by which the purposes of the

white leaders were carried out. The material and moral ruin wrought under this infernal conjunction of ignorance

and intelligent vice was far greater than that inflicted by war. The very foundations of public virtue were

undermined, and the seeds of hatred were thickly sown between the races."

Governor Zebulon Vance

The 1876 Centennial:

“The greatest of [the] Revolutionary centennials – the celebration of the birth of the American nation – was held

in Philadelphia in 1876. An occasion so completely engaging the attention of the country and participated in

so widely drew forth much discussion in the South.

Some Southern leaders opposed their section taking part; they still felt that the country was not theirs and

that it might be less than dignified in themselves and lacking in respect for their Revolutionary ancestors,

to go to Philadelphia and be treated as less than equals in a Union which

those ancestors had done a major part to found.

Former [South Carolina] Governor Benjamin F. Perry saw in the Centennial and effective way to drive

home to the country the similarity of principles of the rebellion that became the Revolution and

the rebellion that became the “Lost Cause.”

“This Centennial glorification of the rebels of ’76, cannot fail to teach the Northern mind to look

with more leniency on Confederate rebels who only attempted to do in the late civil war what the ancestors

of the northern people did do in the American revolution….It shows want of sense as well as want of principle,

and a want of truth, to call the rebels of 1776, patriots and heroes, and the rebels of 1861, traitors.”

Only one contingency would induce a Virginian to not take part. The [Northern] Grand Army must not

be represented: “It would be the death’s head on the board; the skeleton in the banquet hall.”

(The South During Reconstruction, E. Merton Coulter, pp. 389-390)

Bibliography and Sources:

Lee's Last Major General, Bryan Grimes of North Carolina, T. Harrell Allen, Savas Publishing, 1999

Walter Clark, Fighting Judge, Aubrey Lee Brooks, UNC Press, 1944

Reconstruction, Political and Economic, 1865-`877, William A. Dunning, Harper & Brothers, 1907

Empire of the Owls, H.V. Traywick, Jr., Dementi Milestone Publishing, 2013

Copyright 2011, North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission