North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

"It is ironic that while serving in the prewar United States Navy, Captain John Newland Maffitt was the bane of

New England slavers who still trafficked in human cargo just before the war; and Maffitt as commander of the

USS Crusader in May 1860 captured off Cuba the slaver "Bogota" of New York with 500 Africans aboard---

all purchased from the African king of Dahomey. Captain Maffitt would become one of the

American Confederacy's most illustious blockade runners."

At Sea: The Naval War in North Carolina

Loyalty to Family, Kin, Fireside and State

“Frederick Seward, in his biography of his famous father, conveyed a feeling of justified paranoia

[as Southern men left US government positions]. During March [1861], “nearly every day was bringing

intelligence of some military or naval officer, or some civilian functionary of Southern birth who deemed that his

primary allegiance was due to his seceding State and not the Federal Government.”

(Dudley, page 10)

Reasons for Resignations from the United States Navy

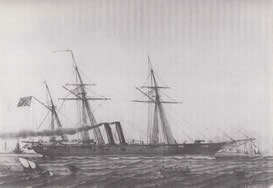

CSS Florida

Loyalty to the Constitution, Not the Government

In his book “Going South, US Navy Officer Resignations and Dismissals,” author Dudley points to

“the requirement of the Lincoln administration that an oath of loyalty be sworn to the United States government.”

This was indeed a strong factor which helped accelerate resignations of officers of Southern birth who understood

that they were being forced to swear an oath to the government rather than the United States Constitution. It was

perhaps for the first time that civilian government employees were being required to swear the same government oath.

Dudley continues that “In the Navy, loyalty oath forms were printed and sent to all ships and stations where

commanding officers demanded compliance. Refusal to comply resulted in a virtual forced resignation

(Dudley, page 13).

One Marine captain stated in his letter of resignation that “In entering the public service, I took an

oath to support the Constitution, which necessarily gives me the right to interpret it. Our institutions,

according to my understanding, are founded upon the principle and right of self-government. The States,

in forming the [original] Confederacy did not relinquish that right, and I believe each State has a clear and

unquestionable right to secede whenever the people thereof think proper, and the Federal Government has no

legal or moral authority to use physical force to keep them in the Union.” Entertaining these views, I cannot

conscientiously join in a war against any of the States which have already seceded or may hereafter secede,

either North or South, for the purpose of coercing them back into the Union…”

(Dudley, pp. 21-22)

James Iredell Waddell

Captain James Iredell Waddell, who was in May, 1861 serving aboard the USS John Adams, resigned his

commission with a letter stating that “The people of North Carolina having withdrawn their allegiance

to the Government of the late Confederacy of the United States…I return to “His Excellency the

President of the United States,” the Commission which appointed me a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy…

in thus separating myself from association which I have cherished for twenty years, I wish it to be

understood that no doctrine of secession, nor wish for disunion of the States impel me, but simply

because my home it the home of my people in the South, and I could not bear arms against them.”

(Dudley, page 23)

Ironclad Strategy for Defending North Carolina's Waters

By September, 1861, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory had begun concentrating on building

armored warships with the American Confederacy, declaring that he would “put his faith in a few powerful ironclads.”

In a report to President Davis he stated that “The judgment of naval men and of other experts in naval construction

have…been consulted [and] …it is believed, enable us with a small number of vessels comparatively to keep our

waters free from the enemy and ultimately to contest with them the possession of his own. The two ironclad frigates

at New Orleans, the two plated ships at Memphis…and the Virginia are vessels of this character.”

Stephen R. Mallory

In March, 1862 the ironclad Virginia made history in its successful attack upon Northern blockaders at

Hampton Roads, and gave effective direction to the naval strategy of the South.

Ironically, the strategy of Mallory to defend the rivers and sounds with gunboats emulated North Carolina’s

colonists during the Revolution as they faced formidable British naval power and a blockade. The ports of Wilmington,

New Bern and Edenton were to be the sites of the fledgling North Carolina naval force of three ships.

“In March, 1777, naval officer John Forster of the brig General Washington under construction at Wilmington wrote

to Governor Richard Caswell that he was “much afraid…she will be delayed much longer than I could wish for want of

Hands, as from this Port being so long blocked by the King of England’s ships, most of the seamen have enlisted in

the Land service….as none are to be got her, I see no prospect of her being manned….”

(Dunkerly, pp. 125-126)

Two British warships had effectively closed the port at Wilmington, cutting off trade and sinking several ships at

anchor at Brunswick Town. Despite North Carolina’s plans to build a navy to combat the British blockade, the

completed ships like the General Washington were greatly outgunned and unable to leave port. Nonetheless,

privateers like the Coatesworth-Pinkney outran the British blockaders in May of 1777, setting the example for

Southern privateers eighty-some years later.

On the Atlantic coast, Virginia-designer John L. Porter’s “Richmond class” ironclads were to be constructed at

existing navy yards at Richmond, Wilmington, Charleston and Savannah, plus temporary shipyards in

North Carolina to build the Albemarle and Neuse. In the case of the Albemarle, builder Gilbert Elliot created a

“cornfield shipyard” at Edwards Ferry with a commissioning of the ship in April, 1864; the Neuse was built at

White Hall (now Seven Springs) at the same time by Howard and Ellis.

Both of these ironclads were their own 152' long class and commissioned in mid-April, 1864, the CSS Albemarle

under Captain James W. Cook; the CSS Neuse under Commander R.F. Pinkney.

CSS Albemarle

In Wilmington, the construction of the CSS North Carolina was at Benjamin Beery’s shipyard on

Eagle’s Island opposite Wilmington on the Cape Fear River. It was laid down in late 1862 and commissioned

in December, 1863 under Commander W.T. Muse; the CSS Raleigh was laid down in early 1863 and commissioned

April 30, 1864 under the command of Captain J. Pembroke Jones. Both were “Richmond class” ironclads at 173’ of

length with a 54’ beam; the John Porter-designed CSS Wilmington was under construction at Beery’s Yard at the

time of Fort Fisher’s capitulation in mid-January, 1865, she was burned on her stocks to prevent capture and use by the enemy.

Confederate Privateers at Sea

Southern privateers and blackade runners like Capt. John Newland Maffitt and Capt. James Iredell Waddell were an

integral part of the Confederacy's defense, as much-needed munitions and supplies were brought into Wilmington

despite the Northern blockade. They also took the war to the high seas and around the world, and devastated

the Northern merchant marine.

Value of the Confederate Cruisers:

The [Confederate] cruisers were not able to win the war, but relative to their cost they did far more damage to

the United States than any other class of military investment made by the Confederacy. In terms of damage to

the long-range economy of the United States, the cruisers were more effective than any other single effort

made by the Confederacy during the war.”

Historian Frank Lawrence Owsley, Jr., CSS Florida, page 10)

“[To effect]….the destruction of [Northern] commerce, the degree of their success was unbelievable.

The American flag, which in the 1850’s had flown over almost as many merchant ships as the British, was

nearly swept from the sea, a blow from which the United States merchant service did not recover until 1918.

The direct damage caused by the cruisers has been estimated at between $15,500,000 and $25,000,000,

and represented a loss of about 200 ships actually destroyed by the raiders. Of this amount the Florida and

the ships she outfitted accounted for $4,051,000 worth of commerce as compared with $4,794,000 for the

Alabama and $2,041,000 for the Shenandoah.

(The CSS Florida: Her Building and Operations, page 159-160)

Sources & Bibliography

Going South, US Navy Resignations & Dismissals on Eve of War, Wm. S. Dudley, NHFP, 1981

Iron Afloat, The Story of the Confederate Armorclads, USC Press, 1985

Confederate Ironclad, 1861-1865, Angus Konstan, Osprey Books, 2001

Redcoats on the River, Robert M. Dunkerly, Dram Tree Books, 2008

Copyright 2011, North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial Commission