North Carolina War Between the States Sesquicentennial

Regimental Flags From the Ladies Hands

The following is reprinted with permission from

"Blood and War at My Doorstep, North Carolina Civilians in the War Between the States,"

Chapter 2, Volume I, Brenda Chambers McKean.

This two-volume set is highly recommended for its primary source material from period diaries and recollections,

and its unique insights into life on the homefront in North Carolina during the War Between the States.

"Making Flags"

North Carolina women did not wait for the State to secede before they began making flags. With patriotic fever

high as the men in the neighborhood formed companies and practiced drill, it was assumed that the State would

also leave the union and the men would need flags.

Research gives evidence of several flag controversies as to whom actually sewed the first.

It appears that the glory may go to the ladies of Little Washington.

“The first flag displayed in Little Washington was made at the home of Sam Waters,

by Mrs. S.B. Waters, Mrs. Claudia Benbury, Miss Jeanette McDonald, and Miss

Sarah Williams, and was flung to the breezes from the window over the door of the

court house on the occasion of a speech in favor of the doctrine of States’ Rights,

and secession, delivered by William Rodman, and replied by David Carter, in the

Fall of 1860.”

Confederate General W.A. Smith told post-war that the First Secession flag was presented on February 1, 1861,

by a group of fiery secessionists from Anson County who made a flag of calico, with two large stars at the

head, marked South Carolina and Mississippi, “the first two States severing their relations with Washington [DC].”

From these stars led stripes of alternating red, white, and blue: and in the lower corner at the tail end was

another star of like proportions half turned down marked “NC”, representing North Carolina faint and drooping,

hanging her head in dishonor, shame, and disgrace. In large letters at the top of the flag was the word “Secession.”

Underneath was this motto: “Resistance to Oppression is in Obedience to God.” Research revealed that these

“fiery secessionists” were four men, T.A. Wadell, J.B. Wadell, W.A. Threadgill, and J.M. Wright. Miss Kate Smith

and Winnie Wilkins pinned silk rosettes on the flag makers.

The flag was hung in the night and immediately upon dawn residents of Ansonville objected. Later that night

two men climbed the pole and cut the flag down. The original makers of the first flag were not staunched in

their efforts. In the morning Mrs. Garrett and the young ladies in the town stitched another larger flag showing

more stars. It carried the same motto. This was hoisted that afternoon. Some in the village refused to walk

under the flag. This flag was later presented to Governor John Ellis by Anson County soldiers.

Professor Gilliam, a teacher at the Carolina Female College, was at first against secession, but he softened up,

changed his mind, then gave a speech under the second secession flag condemning the North for its

“aggressions against the South, and their repudiation of the States` rights, for their contempt for the

Constitution…” A picket was posted to guard this flag until the town cooled off.

The flag at the college was raised twice.

The one on top of the store was cut down and then replaced.

However, another claim to the first flag of Washington was from the needles of Mrs. F.C. Roberts and

Miss Manly who presented it to the guardians of Fort Macon in April of 1861. “The Old State Flag” pictured

a rattlesnake entwined around a pine tree and the flag was so big they had to stretch it out the full length of

the room in the Masonic Hall to sew it. Later on Fort Macon received and flew the garrison flag similar to the

Stars and Bars. Susan Roberson with her sisters made this flag by ripping up the United States

flag and restructuring it.

James A. Graham, stationed at Fort Macon, wrote to his mother on May 8, 1861:

“Some ladies came over from Morehead City the other day and brought us a Southern Confederate flag.

We hoisted it and fired a salute of nine guns.”

Perhaps this was the same flag sewn by the Roberson sisters.

In May, 1861, eleven girls representing the eleven Southern States that seceded stood on a porch in

Little Washington as Miss Clara Hoyt presented a flag to the Washington Grays. Spirits were high as the band

played when the young men marched to the wharf followed by the citizens, some crying, most waving their

hankies, and others throwing flowers over them. These recruits were stationed at Portsmouth which was a

resort town pre-war. The wives of the officers moved there and many, many young girls followed, chaperoned

by the older women. All stayed there until the fall of Fort Hatteras in February, 1862.

A flag presentation from the ladies of Washington to the Jeff Davis Rifles,

captained by J.R. Corner, June 21, 1861, was featured in the newspaper:

Dear Sir:

It is our pleasant duty to present you and your gallant company with the accompanying flag. The ladies of

Washington have made it for you. With every stitch has been woven[,] thought of the gallant men who are so

soon to risk their lives in our defense, perchance some silent tears have spoken of feelings too deep for

utterance, but think not, our tears flow from any cowardly wish to withdraw those we love from this glorious

contest. Not so, our hearts may be wrung with sorrow but the ladies of Washington, believing that their

cause is a righteous one, and trusting in God for his aid and protection, would urge you on, by every call of

honor or duty, by every tender tie, by your duty to God and to your country, by your love for your mothers, wives,

and children, to protect our homes and our rights. We do not say, "Protect our flag, let it not be disgraced":

we have no fear for that; in giving it to you, we know that it will be preserved with honor, and we look forward with

pleasure to (we hope) the not too far distant day, when you will return to us, and we only claim the privilege of

wreathing it with laurels which we know you will win for it. And now in bidding you farewell, we would pray that

The Lord of Hosts be “round about you as a wall of fire, and shield your heads in the day of battle.”

In behalf of the ladies of Washington: Mrs. T.H.B. Myers, Miss Annie C. Hoyt, Miss M.M. Fowle.

This particular flag was made from the satin wedding gown of Mrs. Myers.

When Rufus Barringer joined the army, local ladies from Cabarrus County presented his unit with a flag on

May 18, 1861. Ladies in Gaston County made flags from their dresses for the “Gaston Blues”

and the “Watauga Minute Men.”

Orren Randolph Smith who designed the first Confederate flag asked Miss Rebecca Murphy, of Franklin County,

to sew it for him. She cut the cloth twelve inches by fifteen inches from flour sacks. He designed 7-stars because

only 7 States had seceded by February, 1861. This little model, he sent to the Confederate Congress at Montgomery,

Alabama, and it was adopted on March 4, 1861. Mr. Smith bought additional fabric and asked Miss Murphy again,

to make a larger flag of the same kind. She completed it on March 17, 1861. Rebecca’s sister, Sarah Ann, refused

to help stitch the flag because she held Unionist sympathies.

O.R. Smith said, “whether the flag committee accepted my model or not, I was determined that one of my

flags should be floating in the breeze.” Henry Lucas, a free black man, cut the pole and Smith’s flag was raised

over the courthouse in Louisburg. Unfurled, it flew until Sherman’s forces cut it down.

A third flag was assembled from Smith’s design. The ladies of the community made a flag for the Franklin Rifles,

and presented it to the company. It was a silk flag with heavy silver fringe and carried the words:

“Our Lives to Liberty, Our Souls to God, Franklin Rifles.

Presented by the Ladies of Louisburg, North Carolina, April 27th, 1861.

The flag dispute arose in 1904 when the magazine Lost Cause printed an article that the Frenchman,

Peleg Harison, and Nicola Marshcall claimed credit. Major Smith’s daughter disputed this and the flag controversy

was on. “Orren R. Smith’s claim to have designed the Stars and Bars was investigated by a committee of the

United Confederate Veterans in 1912 and upheld against other claimants.”

The flag controversy continues but research shows the last word as to who was first.

The first Confederate flag was hoisted March 4, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama. “William Porcher Miles,

head of the Committee on Flag and Seal of the Provisional Confederate Congress in Montgomery, Alabama,

detailed the selection of the First National flag via the committee.” Neither Major Smith nor Nicola Marshcall’s

design was the first according to researcher Greg Biggs. He said official documents in the Library of Congress show,

“Smith’s claim states that it was after Ft. Sumter that he got the ideal for the flag.” Marshcall purportedly gave his

design to a lady who took it to governor of Alabama “to be presented to Miles.” Mr. Biggs further states that in the

National Archives the names of the two men do not appear in the records. According to Porcher Miles this

committee designed the flag that was accepted.

In April of 1861, the embroidery class at Wayne Female College assembled a silk flag. Class members,

Miss Corinne Dortch, Mrs. Thomas Slocumb, and Mrs. Broadhurst, used these words on the flag:

“Goldsboro Rifles, Victory or Death.”

The college closed in 1862 and was then converted into a hospital. A Confederate flag was constructed by the

ladies of Littleton for the Roanoke Minute Men, Company A, 14th North Carolina Troops.

Before the “Oak City Guards” left Raleigh for the seat of war, they were presented a flag on June 1, 1861

stitched by Mrs. F.L. Wilson, and handed-over through her husband, who delivered a very appropriate poem

as the young recruits were leaving for Virginia. Another gala sendoff was in progress at the same time in Morrisville.

Miss Fanny Lyon gave a speech while presenting a flag to the Cedar Fork Rifles.

Reverend A.D. Blackwood gave each recruit a Bible.

Other ladies who made flags for different units were the students of St. Mary’s who sewed the flag for the

Ellis Light Artillery. Miss H. Weatherspoon wrote a short note to the Raleigh Standard which said that the local

ladies had formed an aid society and presented a flag to former professor R.W. York who was captain of the volunteers.

In Charlotte the Hornets Nests Riflemen were bestowed a beautiful flag.

The last paragraph of Miss Sadler’s speech went:

“The prayers, the hopes, the hearts of our ladies go with you. We feel success will crown our banner.

We have no room for fears. To God and our community we devote you.”

Also in Charlotte, a hand-painted flag was presented to the Charlotte Grays by Miss Hattie Howell.

Her speech was short and sweet: “Captain [Egbert] Ross, I present to you this flag for the Charlotte Grays,

knowing that whatever happens it will never, while a man of you lives, be lowered in disgrace.” After the usual

words of thanks, Captain Ross explained,

“…we promise you, in the name of the Charlotte Grays will never see it dishonored.

We may die in its defense, but dishonored it shall never be.”

North Carolina Military Institute

On May 8, 1861, the following beautiful and inspiring address was delivered at Charlotte, by Miss Ann E. Wilson,

on presenting a flag of the Confederate States to the cadets of the Military Institute, before they left for

the military encampments near this city:

“I have been commissioned by the young ladies of Charlotte to present to you this beautiful ensign,

the FLAG OF OUR COUNTRY. Here upon the revered soil of Mecklenburg we commit to you, not simply

the fabric of which this banner is made, nor only the hopes and wishes of its donors, but we commit to your

keeping, the dearest cause we have, the cause of JUSTICE AND HUMANITY.

For the good of your country, you have shown a laudable desire to leave your Institution of learning and

many pleasant associations which you have formed here, and go in the defence of our rights, and whilst many

a tear of friendship will flow, and many a bright hope be crushed, yet we bid you `God speed` in this great work,

and may the God of BATTLES, and the God of NATIONS, and the God of JUSTICE protect and defend

you. The South has been called upon for her jewels, and like Cornelia, the mother of Gracchi, she presents

her sons. Already this flag with its bright galaxy of seven stars, whose luster has been increased by an

eighth, Virginia, and the reflection of a ninth, North Carolina, is waving in triumph over Sumter, and unfolding

its pure and unsullied folds to the boys of the entire South. In this cause and under this flag, you will take into

battle, and recollect, that wherever you may be, you have our kindest wishes, our sympathies and our prayers.

Let me say, now, in bidding you adieu, that we know to whom we have confided this sacred trust, and we have

the highest assurance, that when the `thunder of war` shall be heard no more, and the glad tidings of peace shall

spread over our land, we shall welcome the return of this banner with honor and victory perched upon its folds,

or it will become the winding sheet of the brave hearts and strong arms, which have borne it to the battle field.”

“Go forth then ye brave where glory awaits you,

The voice of your country exultant, now greets you;

The good and the true with favor regard you,

And the smiles of the fair with blessings reward you.”

````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````````

“May 15, 1861, made flag for the homeguards at Ringwood,” writes Mrs. Elizabeth S. Wiggins of Halifax County

in her diary. She was fifty-seven years-old and would later have seven sons serving in the war.

Catherine Edmondston penned in her diary: “…. tomorrow the ladies of Scotland Neck present to the

Scotland Neck Mounted Riflemen a flag. The Edgecombe Guards, the Enfield Blues, the Halifax Light Infantry

are coming and they gave a grand ball to the ladies. The flag is a beautiful one of blue silk with heavy bullion

fringe & tassels. One side is the oat of arms of NC surrounded by gold stars, one for each state; on the other

a wreath of corn in the silk & ripe ear, cotton in blossom & bole, & wheat encircling the words Scotland Neck

Mounted Riflemen -- organized Nov 30th, 1859, & on the ribbon which ties the wreath the words, ‘Pro aris et focis.’

The staff represents a corn stalk surmounted by a battle axe---peace and war juxtaposition!”

Young women of Henderson County “presented the young men with a beautiful flag, white with fifteen

blue stars, emblematic of the Southern States, radiating from the center, forming one large star. On the

reverse side is worked in blue and white `To the Henderson Guards, follow your banner to victory or death.”

The ladies of Asheville donated a flag they had made to the troops known as the “Watauga Rangers.

Young and old alike took food and treats to the training camp.

Caldwell County ladies constructed a flag, as did the young women of Lenoir County,

and the women of Hendersonville. In Shelby, ladies sewed a flag and

Miss Julia Durham was chosen to render the speech.

Over the courthouse in Jefferson flew a flag constructed by townswomen.

Amid fanfare “The Yadkin Grays Eagles” were presented a silk flag June 17, 1861.

Miss Louise M. Glen, Mrs. Mary Lilley Conelly, Miss Fannie Conelly, Miss Elizabeth Glen and

Miss E.S. Conrad are given credited for the construction. This particular flag, fashioned from the

donors’ dresses, was embroidered with the words:

“We scorn the sordid lust of pelf, and serve our country for herself.”

The captain of the Eagles finished his speech with the words: “When this cruel war is over, Miss Lou,

this flag untarnished shall be returned to you.”

The Raleigh Standard printed word for word the presentation from ladies of Morrisville to the North Carolina Grays on June 5, 1861:

“Captain York drilled the men, had a dress parade, and much singing, Miss Fanny Lyon stepped forward

and presented the Cedar Fork Rifles with a flag the ladies had made:

“Gentlemen, I have been commissioned by the young ladies of Cedar Fork, to present to the brave sons

of this vicinity, this beautiful ensign. Indeed it charms me that I have the pleasure of presenting to this,

I must say beautiful and brave men of North Carolina. This ensign showing to the world the eagerness of the

young ladies in assisting their brothers, and attached friends, in defence of their country. We can help only

by our prayer -- we regret very much that we cannot help them more.

For the good of your country, you have shown laudable desire to leave your institution of learning, various

occupations, and the many pleasant associations which you have formed here, and go to the distant part

of the country, to aid in the defence of our rights, and while many a tear of friendship, of sympathy, shall flow

for the brave and noble sons of this company, we promise you our kindest wishes, our sympathies and our prayers.

Be of good cheer! Do not fall, or be crushed in the hands of despair. I have one dear brother -- with all the timidity

due my sex, I am ready to offer him up in defence of our country's rights and honor; not with grief, but thanking

God that I have one brother to offer. May he, and this noble company, prove to be faithful,

intelligent and chivalrous sons of the South.

When the direful contest is over, and the patriotic husband, brothers, and friends return, the ladies of Cedar Fork

will meet you with tears of joy, the smile of welcome, the bosom of delight,

and the embraces of pure and unsullied affection.’

In behalf of our society, I now present to the North Carolina Grays,

this beautiful flag. We bid you all God's speed."

The speech of acceptance was made by one of the officers of the company, Lt. Malcus Williamson Page.

“Afterwards the ladies of Cary served a meal to the crowd. Later Reverend A.D. Blackwood preached

a sermon and gave a Bible to the military company.”

The Eleventh Regimental flag, sewn by the women of Windsor, though torn and patched, survived the

war and was secretly burned at Appomattox. Captain Edward Outlaw was able to cut a small square from

the flag before destroying it. Mrs. Patrick Henry Winston, Miss Webb, and the Misses Outlaw

are credited with constructing this flag.

The Ellis Flying Artillery marched to the St. Mary’s campus to receive their flag constructed by the

students. Not to be outdone, students of the Salem Female College completed a flag for the Forsyth Rifles

commanded by Alfred Belo. Forming up on the square in town, the men listened to the Reverend George

Bahnson as he prayed for their safety and to resist “temptations of a soldier’s life.”

H.W. Barrow, member of the Twenty-First Regiment, said

“The ladies of Danville [Va.] say we have…the best looking flag in camp…”

Forsyth County’s flag, “made for Co. I…..was sewn by Misses Bettie and Laura Lemly, Nellie Belo,

Carrie and Mary Fries [sister of John Fries]. It was made of red, white, & blue silk and embroidered in

large letters with yellow silk, on the white side, with the words ‘Liberty or Death.’ A second flag was made

by the same young ladies. They could not get any more silk like the first [,] so used white silk for the

whole flag, embroidering it in blue silk….both of these flags were presented to the Forsyth Rifles.”

A third flag was constructed for Company G, Captain W. Wheeler’s men, based on the first national

pattern sewn by Lavinia Boner, Laura and Bettie Lemly, Kate Kremer, and Addie Shober.

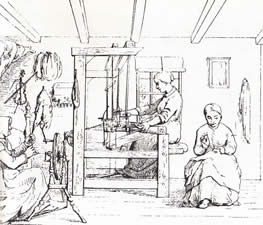

Skirts that women wore in the mid-nineteenth century enveloped a wire hoop. It took a minimum of five yards

to cover the bell shape of the hoop. It is no wonder that these skirts contained enough fabric to make flags

and they were used for that purpose. It also makes for a romantic story to tell future grandchildren.

In Lenoir County Miss Lina Caison made a flag from a dress belonging to Miss Annie Rankin. In another reference

Miss Annie Rankin was given credit for making the flag. This flag was blue with the North Carolina coat of arms

painted on by Annie’s sister. On July 31, 1861, in Hickory, Miss Norwood presented this flag to Captain Rankin

of the Twenty-sixth Regiment, Company F. They were known afterwards as the Hilbriten Guards. Little girls wearing

white dresses with blue sashes took part in the ceremony representing the thirteen seceded States.

The Buncombe Rifles carried a flag made from the silk dresses of Misses Anna and Lillie Woodfin,

Misses Fanny and Annie Patton, Mary Gaines, and Kate Smith of Asheville.

Other students recorded who executed flags were the girls from the Chowan Institute presenting theirs to the

Hertford Light Infantry. In Greensboro the students of Edgeworth School and Mary Morehead had this to say:

“In the name of my subjects, fair donors of Edgeworth, I present this banner to the Guilford Greys. Fain would

I have it a `Banner of peace` and have inscribed upon its folds, `Peace on earth good will to men;` for our womanly

natures shrink from the horrors of war and bloodshed. But we have placed…upon it `the oak`--fit emblem of the

firm heroic spirits over which it is to float. Strength, energy, and decision mark the character of the sons of

Guilford, whose noble sires have taught their sons to know but one fear---the fear of doing wrong…Proudly in

days past have the banners of our country waved o`er yon battlefield, where our fathers fought for freedom

from a tyrant’s power. This their motto--`Union in Strength`, and we their daughters would have this our

banner unfurled, only in some noble cause, and quiveringly through our soft Southern breezes echo

forth the same glorious theme, Union!, Union!

Henry Gorrell collected the flag and made his acceptance speech:

“In time of war or in time of peace, in prosperity or in adversity we would have you remember the Guilford Grays;

for be assured your memories will ever be cherished by them. And we would have you remember that we are

all in favor of union- -- union of States, union of hearts, union of hands,

union now and forever, one and inseparable.”

In Tarboro Mrs. Anna McNair sewed the flag and Miss Cornelia Crenshaw gave it to the Edgecombe Guards.

The Arsenal’s United States flag in Fayetteville was removed and replaced with the State flag.

The Stars and Stripes was given to the town women who converted it into a Confederate flag “when the

Stars and Bars had been settled upon.”

The ladies of Fayetteville stitched a flag for the First Regiment 1/11th. “To commemorate the fight

[Bethel, Virginia], the legislature adopted a resolution calling for a special flag for the First Regiment.”

The ladies of Fayetteville drew the assignment to make it. The regiment was near Yorktown, Virginia,

when the flag was finished, so John Baker, Jr. carried it to the camp and presented it to the troops.

At Floral College in Robeson Count, “The Highland Boys,” received a flag in July of 1861, then boarded the

train and left Shoe Heel [presently Maxton] to the tears of the females.

Sergeant L.J. Hoyle, of “The Southern Stars,” from Lincoln County, received a flag from the fair hands of

a gentler sex. The recruits left for Raleigh and stayed in the basement of the Baptist Church until continuing on to camp.

Ladies of Wadesboro sewed a silk flag and it was painted by Lemuel Beeman. They marched to Cheraw [SC],

took the train to Florence, South Carolina which went to Wilmington, then into the Raleigh training camps.

Recruits from Carthage, after an all day celebration, took the train to a distant camp. In addition, the day they left,

they were given a large meal by townsfolk and each member of the company was presented with a small silk flag

by Mrs. Eliza Short. On one side of the flag appeared these words:

“Our cause is just, Our duty we know. In God we trust, To battle we go.”

The other side of the flag read:

“We are sending our boys, Our best and bravest, Oh, God protect them, Thou who savest.”

The Sixth North Carolina State Troops ensign came from a ladies blue shawl. Miss Christine Fisher, who

had stitched the flag for her brother, which he took with him to Manassas, featured the State seal with the

words, “Do or Die” on one side and the reverse read, “May 20th, 1775.”

Unfortunately he was killed. Other girls in Salisbury stitched a flag for the Rowan Artillery.

Mrs. Robert Ransom alone constructed the flag carried by the First N.C. Cavalry. “She requested that the flag

never be surrendered, and after the fall of Appomattox, one of the men wrote, they never surrendered it but

sunk it in the river.” Other women acting alone in sewing flags are Miss Rachale McIver who gave a flag to

the Twentieth N.C. T. and Mrs. W.T. Southerland whose husband’s company became the Milton Blues.

On that flag appeared the words: “On to Victory”. It is believed that Mary B. Clarke made

the flag for her husband’s regiment, the 14th.

“While the North Carolina Assembly was struggling to prevent having a flag on the capitol, a Raleigh

newspaper reported on April 24, that the flag of the Confederate States of America had been run

up on the capitol ….” It must be remembered that many of the congressmen at this point were of Union

sympathies. Some thought a United States flag was more appropriate. The US flag was rejected and at

the first secession, Convention members voted to have a State flag. William Browne, a local artist

designed this flag. The secession flag is similar to the present North Carolina State flag.

Women continued to construct flags as needed. Silk, although a very strong fiber, did not stand up to the

heat and weather so it was not unusual for them to make another. Wool bunting became the preferred

fabric of choice. Wilmington ladies sewed the second national Confederate flag which flew

over Ft. Fisher from December, 1864, to January 1865.

The story of flag makers is not complete, but this gives the reader some examples.

“The Stars and Bars are furled, but loved the same,

And through the bloody stains we love the name

Of Stars and Stripes, for which we fight today,

The old flag is not lost, but laid away,

So do not say, FORGET!”

Anonymous (43)

Copyright 2011, North Carolina War Between the States Commission